SANDISFIELD — Either they're smart and wore a head net bug shield, or they're constantly flapping their hands as they man their work sites.

Such is the case now here at Otis State Forest, as Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co. workers and security have found themselves in a place where little mayflies can torment even the sturdiest construction worker or former military man working a detail for the Kinder Morgan subsidiary.

"I was in the Army — boot," said one security guard parked near the company's valve station on Town Hill Road. He began to wave at flies immediately after rolling down his window to talk.

And that's all he would say, since everyone around here has been instructed not to talk about anything to do with Tennessee Gas' Connecticut Expansion Project, a natural gas storage loop being added to an existing pipeline corridor. When asked if there had been any security problems so far, he shook his head.

He did nod, however, when asked if he had been hired by Edward Davis LLC, a large Boston security firm started by Davis, a former Boston Police Commissioner at the helm during the Boston Marathon bombing.

Davis' firm provides a host of "security solutions" and training and employs experts "specially trained and served in all levels of government, military and federal agencies — including former U.S. Navy Seals, U.S. Secret Service members, major city police department chiefs and private security sector experts."

When asked what specific threats to this section of the 13-mile, $93 million tri-state project, Kinder Morgan spokeswoman Sara Hughes said she had to decline comment on "security-related matters."

The Davis firm did not return calls for comment.

The pipeline company's private security has been visibly scaled back, after initial concerns about protests at the start of work in late April, and a total of 24 arrests of protesters ever since.

But residents and protesters report a series of brushes with security forces associated with the project — nothing serious, perhaps, but enough to maintain a feeling of relative unease in the community.

The pipeline project has been controversial on a number of grounds including environmental concerns, questions about the need for the extra gas this new line will provide, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's approval process, which lately has been criticized by a group of U.S. lawmakers, including three who represent Massachusetts.

But the big issue was the legal precedent set by Tennessee Gas winning an easement on about 2 miles of state owned land protected by the state Constitution through Article 97. This made tree cutting near an old growth stand of hemlocks in Otis State Forest the focal point of anti-pipeline activists, and what according to state police Lt. John Pinkham, likely prompted heavy security presence.

Muddy waters

"Given the history of pipeline protests," Pinkham said, "[Kinder-Morgan] was concerned about protecting their large investment."

Yet no one will say from exactly what. Of the 24 arrested, only a few were under the age of 65, and part of a group committed to nonviolence.

While some state police troopers have been on duty here, others are hired by the company for details or overtime, Pinkham added, noting that this does not come at taxpayer expense.

"The company reimburses the state — it's not a check from Kinder-Morgan to the troopers."

He said there was a firewall here.

"[The state] wants to keep troopers insulated from influence by Kinder-Morgan or any company," he said. "We are not mercenaries hired by Kinder Morgan."

But resident Steven Rubenstein, who lives off a road near the valve station, said he saw two troopers helping the company navigate a rural town with narrow roads, many of which are dirt.

"Why aren't they turning around at the valve station?" he said.

Tractor-trailers loaded with equipment and wooden beams were using Rubenstein's road, Mountain Home Lane, as a place to turn around before making their drops at the valve station on Town Hill Road.

"There's always a little dip in the road and when it rains there's always a puddle," Rubenstein said. "They're tearing up the side of the road. And when they make the U-turns it's making it worse. Even a Mini Cooper got stuck in [the puddle]."

He said there were two young children who frequently ride their bikes on the road, and he worried about their safety.

So Rubenstein took it upon himself to stop it. First he checked with the town and state police to make sure it was legal to park on the side of his road.

"They said it was a public road and was fine," he said. "And there are no `no parking' signs."

He parked each of his cars legally, but in such a way that prevented trucks from turning there.

"That afternoon two state police came to my door, and asked, `Do you own these vehicles? We'd like you to move them.'"

"Why?" Rubenstein asked them.

"You're blocking the road," a trooper said.

"How am I blocking the road if you just went past my cars?"

The troopers then said that if he has a driveway, he can't park on the road.

"Lot's of people park on the road," Rubenstein said.

Rubenstein, who owns one of two houses on the cul-de-sac road, said some big barrels and a "no turnaround" sign did the trick in the end. The troopers never came back.

Down at Lower Spectacle Pond, which is directly across the road from the pipeline work, Otis resident Susan Bryan showed up after two troopers left. She said every time she brings her dog here for a walk and a swim a trooper shows up and "observes me."

Pinkham previously told The Eagle that this sort of thing is unintentional, and that troopers are not concerned with following residents.

But Bryan said it doesn't feel good.

"Now it's a negative, threatening atmosphere," said Bryan, who has lived five minutes away from the pond for 32 years. "This is our most heavenly spot on the planet."

Not standing rock

Protesters, at least so far, are not anything like the fictional characters in Edward Abbey's environmental cult classic The Monkey Wrench Gang, where trees are spiked and equipment sabotaged.

But pipeline companies don't mess around.

A few days ago, The Intercept reported on "more than 100 internal documents" leaked to it by a contractor for the security firm, TigerSwan, about the Dakota Access pipeline protests. Like Edward Davis, TigerSwan — hired by pipeline company Energy Transfer Partners — mobilizes law enforcement and military strategies to protect the interests of the private sector.

Those leaked documents show that "counterterrorism tactics" were used to "defeat pipeline insurgencies" at Standing Rock.

The Edward Davis website says the firm consults both ways: to both the private and public sectors.

Davis, it says, will "conduct complex, confidential investigations for corporations, law firms and individuals," as well as for "local, state and federal government and law enforcement entities on risk mitigation, crisis response management, training, legislative issues, and security policies and protocols."

But with intelligence, a security firm like Davis might have learned that the radical environmental group Earth First has taken an interest in the Otis State Forest situation for several reasons, including a Great Blue Heron rookery close to pipeline work.

Earth First Newswire writer Jenny Elliott-Bennett told The Eagle in an email last month that Earth First activists from the U.K. have come to the area, "including members of the very successful Hunt Saboteurs Association."

That group is known for using nonviolent "direct action" to sabotage fox hunts.

"They flew over site... to get more photographic evidence of nest sites and the destruction, and are on the ground," she added.

Little protest cabin

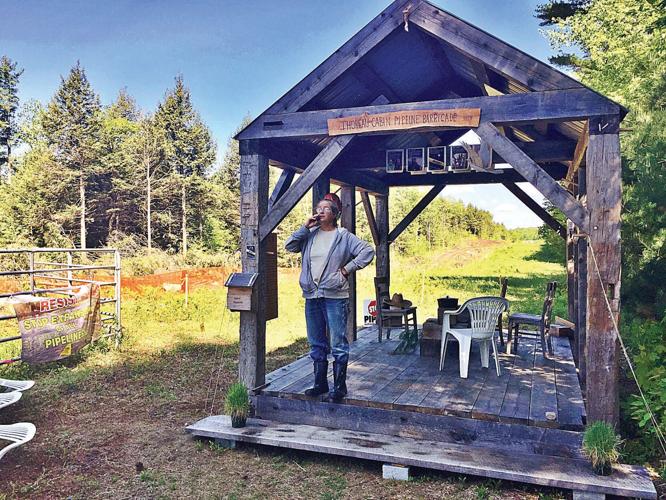

Aside from the protests that led to arrests, the only sign of anarchy so far is a little cabin built by the anti-pipeline group Sugar Shack Alliance. The "Thoreau Cabin Pipeline Barricade" was reassembled on private land next to the pipeline path. It was used once before to protest the larger Northeast Energy Direct Pipeline (NED), a project eventually nixed by Kinder Morgan.

Henry David Thoreau's writings on resistance inspired the cabin, according to its creator Will Elwell. And there it sits, a place to observe Tennessee Gas' work and serve as a staging ground for Sugar Shack members who say they will continue to act as long as the project — set to take another five months — is stopped.

"We still plan to keep on," said Sugar Shack spokeswoman Abby Ferla. "We took a little break to re-strategize and we have a lot of energy left. We are confident we can stop it."

When asked, Ferla said the group was not aligned with any militant environmental groups, and said the group is "deeply committed to nonviolent tactics."

But she said the group is not surprised that Kinder Morgan would hire such an "aggressive" security firm despite the the group's peaceful ways.

"Because we've seen recently, especially at Standing Rock, pipeline companies that are increasingly using paramilitary and intense surveillance to control nonviolent protests."

"Nonviolent protests sound benign, but they brought us civil rights and anti-apartheid, and companies recognize that it is a really powerful tool," Ferla added.

She also said Kinder Morgan's hiring of Edward Davis shows the company is "desperate" to get this project completed, possibly since the NED project was canceled last year.

"So [Kinder Morgan] is willing to play this high stakes game and hire an expensive security company," she added.

Pinkham said state police patrols would scale back over the next week or so, and Sandisfield Police would take over. The state police command unit van is gone from the area, he added.

But company security is still out there, and one in a buggy asked the reporter what she was doing while parked at Lower Spectacle Pond. This was after two state police troopers had just left, saying they were still on the basic patrol.

As trucks carrying pipes and timber pass the pond, Susan Bryan said the protest cabin is a peaceful haven amid the chaos and noise of pipeline work and the discomfort of what she says is an invasive security presence.

"I go to the cabin every day and smudge it with sage," she said. "And I talk to Thoreau and ask him to help us from the other side."

Reach staff writer Heather Bellow at 413-329-6871.