Big Pharma Gets a Big Win From Trump

The president campaigned on stinging criticisms of the pharmaceutical industry and promises to use Medicare to lower drug prices. But none of that materialized in his drug-pricing speech this week.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, one candidate famously claimed that drug companies were “getting away with murder”—using armies of lobbyists to influence Congress and artificially inflating drug prices.

But a lot can change in two years. That candidate was Donald Trump, who aggravated fellow Republicans on the trail with his forceful and blunt criticism of the pharmaceutical industry. Taking a page from the Democrats, he embraced a plan to allow Medicare to negotiate directly with drug manufacturers, promising that such a scheme could save hundreds of millions of dollars and reduce drug prices. When he was asked why the plan, which has circulated around Capitol Hill for about 15 years, hadn’t yet passed Congress, Trump said without reservation that it was all drug companies’ fault.

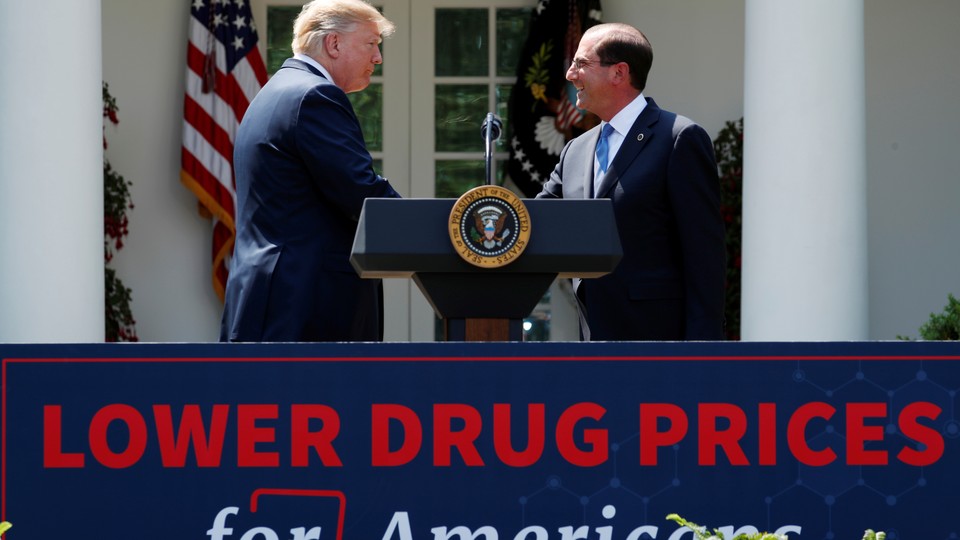

The industry is now having the last laugh. In a speech Friday on drug pricing, President Trump completed his 180-degree turn on Candidate Trump’s promises. The White House’s new plan, as outlined, does seek to address high prescription-drug costs. “We will not rest until this job of unfair pricing is a total victory,” Trump said. But it doesn’t directly challenge the pharmaceutical industry and the direct role it plays in setting prices. Indeed, the new policy largely meets the goals of big pharma, signaling an ever-tightening bond between Trump and drug manufacturers.

One of the major pieces of the plan that Trump outlined Friday is an ongoing effort to change the federal government’s 340B Drug Pricing Program, which provides rebates to hospitals that treat a high share of Medicaid and uninsured patients. Those rebates are intended to lower the cost of care by forcing drug manufacturers to provide medications—especially high-cost drugs for chronic conditions—at cheaper prices to the neediest populations. But the $18 billion 340B program has been the setting for a war between drug manufacturers, who claim hospitals are simply pocketing the savings and not passing them on to patients, and the hospitals themselves. They claim drug manufacturers aren’t actually lowering prices, and instead are using the rebates as an excuse to increase their list prices.

In a policy document released Friday, the White House described its commitment to requiring that safety-net hospitals “use their 340B drug discounts to provide care to more low-income and vulnerable patients.” But an earlier move from the administration undercuts that commitment. Late last year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services slashed the 340B program to the tune of somewhere between $900 million to $1.65 billion, effectively siding with drug manufacturers who say the rebates aren’t worthwhile.

Trump also seemed to take aim at a longtime industry foe in his speech: pharmacy benefits managers, or PBMs. PBMs function as industry middlemen, administering the prescription-drug programs for large insurance programs covering the majority of Americans. These companies handle negotiations between insurers and drug manufacturers on drug prices, including managing rebates from manufacturers that are designed to entice insurers into accepting certain medications on their plans. Drug manufacturers argue that PBMs have wrangled too-high rebates that they keep to themselves instead of passing on to consumers.

In its policy document, the White House vaguely committed to “requiring Pharmacy Benefit Managers to act in the best interests of patients.” Trump was much more forceful in his remarks. “We’re very much eliminating the middlemen,” Trump said, apparently referring to PBMs. “The middlemen became very, very rich.”

Drug companies argue that limiting the 340B discounts and PBM rebates will reduce the consumer costs, especially for elderly people receiving their health care through Medicare Part D. But on that front, Trump has also walked back a major campaign pledge: allowing Part D to negotiate directly with insurers to lower costs of the drugs it offers. Trump said in his speech Friday that “we will have tougher negotiation,” and the policy blueprint released by the White House pushes for “allowing greater flexibility in benefit design to encourage better price negotiation.” But that policy doesn’t seem likely to affect the baseline negotiating capacity of the program: Congress would probably need to pass legislation to allow the health and human-services secretary to make deals with drug companies. Without that legislation in place, Trump has little executive authority to change anything.

While Trump did outline support for a Medicare program that would limit out-of-pocket spending on drugs, that reform seems similarly toothless. That’s because it would have little to do with actual drug prices. Instead, it would increase the amount that Medicare would pay for some seniors’ drugs, in effect shifting more tax dollars toward hiding the true costs of care for consumers.

Perhaps the most impactful set of policies that Trump outlined—and that he actually has the power to pursue—involve what he calls “putting American patients first”: intervening in an escalating drug-price war and increasing research-and-development competition between domestic drug companies and international drug companies. International competition has long been a major focus of drug lobbying, as manufacturers in the United States claim they shoulder most of the burden of research, while price-setting in other countries means they don’t reap commensurate global profits. In response, Trump promised to release a comparison of global drug prices. He also pledged to change drug-patenting and Food and Drug Administration regulation to enhance domestic research and expand the ability of pharmaceutical companies to keep effective monopolies over their drugs.

In all, while the president promised “the most sweeping action in history to lower the costs of prescription drugs for the American people,” the policies described Friday seem somewhat marginal, and none address the actual prices pharmaceutical companies are charging.

Trump seemed to frame his remarks, as well as the new policy outline, as a continued rebuke of the industry, saying “the drug lobby is making an absolute fortune at the expense of American consumers.” But that rebuke falls especially flat this week, given the still-unfolding story that pharmaceutical giant Novartis paid his personal attorney Michael Cohen $1.2 million to gain a better understanding of the president’s health-care policy.

Trump’s policy seems to fall pretty much in line with what Novartis and other pharmaceutical companies have lobbied for years to get. With health secretary and former Eli Lilly president Alex Azar on board to fill in the details, the president outlined a plan that validated longtime drug-industry critiques of Part D payments, rebates, and PBMs. The plan shifts more government money toward obscuring the list prices of manufacturers’ drugs, and takes a protectionist stance on American companies. President Trump calls his plan “American patients first,” but the interests of American pharmaceuticals may be taking priority.