Is it just me or have there been a whole bunch of really scary sounding stories about rising interest rates in the last few months? While some of these worries are warranted it’s important to pan out and take a more objective view of the environment so we can avoid making excessively short-term judgements about what may or may not happen. There’s a lot of people out there who rely on selling you short-term fear in exchange for your attention and your money. So let’s see if I can save you some money and some stress by putting things in a reasonable perspective.

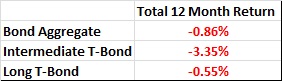

In the last 12 months 10 year bond yields have jumped from 2.2% to 3.05%. Short rates are up even more with the 3 month T-Bill jumping from 0.9% to 1.9%. Sounds like a scary time to be a bond investor, but it really hasn’t. Here’s the 12 month total return on various bond instruments:

That’s not even a flesh wound. Of course, as I’ve described on several occasions, bonds don’t necessarily lose value when rates rise. Bonds lose value in the short-term when rates rise, but rising rates ultimately lead to higher future bond returns as your long bonds become short bonds which then get reinvested in higher yielding bonds. If you’re a bond investor with a reasonable time horizon and some patience you should be begging for rates to rise.

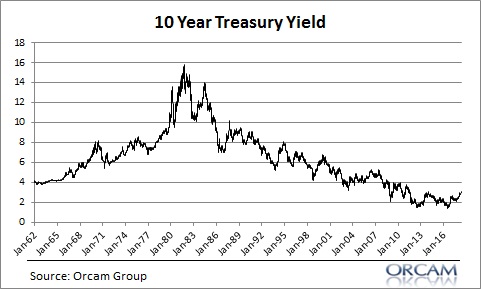

Importantly, the recent rise in yields hasn’t been extreme at all. In fact, this looks like another garden variety counter-trend move that barely registers on a long-term chart of yields:

But the real kicker here is understanding that the total return on bonds has been pretty muted despite rising rates. That’s because the rate of change hasn’t been dramatic by any means. And for bond returns the rate of change in yields and the starting point is everything. In a sharply rising rate environment the interest paid does not always offset the loss in principal.

For instance, if you bought an aggregate bond index one year ago you were buying an instrument that paid about 2.25% with an average effective maturity of 5.9 years. But rising rates have resulted in a 3.11% principal decline leading to a total return of -0.86%. And of course, if you actually hold onto this bond for 5+ years there’s very little chance you’ll see principal losses because the underlying bonds will mature at par and you’ll recoup your short-term principal declines plus you’ll earn the interest all along the way.

Another way of thinking about this is that long and slow interest rate increases aren’t scary for bond investors. It’s the short and rapid changes that can be scary. For instance, from 1940 to 1980 interest rates jumped from 2.5% to 15%. Bonds must have lost money, right? Wrong. A 10 year constant maturity bond fund generated a 2.5% annual return over this period. Not great, but not bad either. That’s because the rate of change in yields was relatively slow and by the time rates started to change somewhat quickly you were reinvesting in what was a fairly high yielding bond portfolio which more than offset the losses from the rate increases. As I’ve written about before, slow rising rates aren’t scary. Neither are high and moderately rising rates. But low and rapidly rising could get a little scary for the impatient investor who can’t ride out the storm.

Is the latter a likely outcome? Well, no one really knows. I’ve pointed out that there appears to be some modest upside in inflation and yields. I’ve also pointed out that the macro trends seem to be putting structural downward pressure on long-term inflation. So the scenario with rapidly rising rates looks unlikely to me. But the real question is, if you’ve got 5-10 years to invest would you rather own a bond that is clipping 3-4% and will guarantee principal return at the end of 5-10 years or would you rather own stocks at very high valuations with a high probability of low and volatile future returns? The right answer is that this isn’t an either/or proposition. Smart asset allocation isn’t an all-in or all-out process. We own both stocks and bonds because we simply don’t know. In order to maintain the courage to own both you have to be able to put the long-term probable outcomes in a reasonable perspective. And that will often involve the ability to ignore scary sounding narratives pumped out by people who have an incentive to sell you short-term fear in exchange for your attention (and money).

Mr. Roche is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Discipline Funds.Discipline Funds is a low fee financial advisory firm with a focus on helping people be more disciplined with their finances.

He is also the author of Pragmatic Capitalism: What Every Investor Needs to Understand About Money and Finance, Understanding the Modern Monetary System and Understanding Modern Portfolio Construction.