But they didn’t use any of the big-name DNA analysis firms like 23andMe; instead they relied on GEDmatch, a free, open source site run by a small two-man Florida company that just a few years ago was soliciting donations via PayPal.

According to the East Bay Times, which first reported the connection to GEDmatch late Thursday evening, California investigators caught a huge break in the case when they matched DNA from some of the original crime scenes with genetic data that had already been uploaded to GEDmatch. This familial link eventually led authorities to Joseph James DeAngelo, the man authorities have named the chief suspect in the case. To confirm the genetic match, Citrus Heights police physically surveilled him and captured DNA off of something that he had discarded.

The former police officer was arrested Tuesday at his home in suburban Sacramento, having eluded law enforcement for decades. DeAngelo is expected to be arraigned Friday in Sacramento County Superior Court.

The Yolo County District Attorney said Thursday that DeAngelo "is suspected of committing over 50 rapes and a dozen murders across 10 different Northern, Central, and Southern California counties between 1976 and 1986."

Paul Holes, a retired Contra Costa County District Attorney inspector, told the East Bay Times that the investigation’s "biggest tool was GEDmatch, a Florida-based website that pools raw genetic profiles that people share publicly. No court order was needed to access that site’s large database of genetic blueprints."

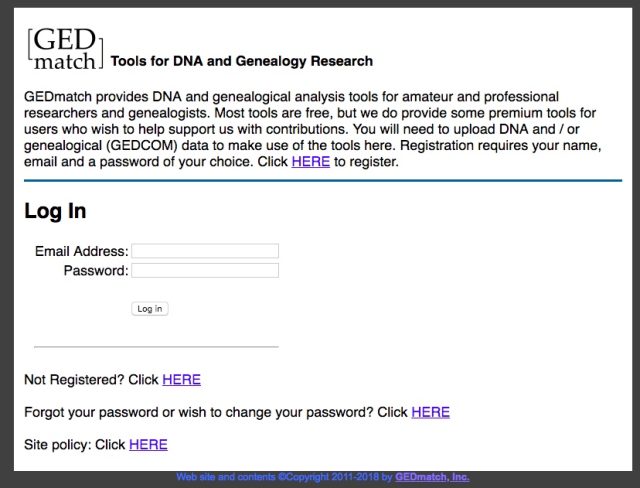

On Friday morning, GEDmatch co-founder Curtis Rogers emailed Ars, underscoring the implications of uploading one's genetic profile to a database such as his. He published a statement, saying that he only learned of his site's connection to the California investigation through the media.

"Although we were not approached by law enforcement or anyone else about this case or about the DNA, it has always been GEDmatch's policy to inform users that the database could be used for other uses, as set forth in the Site Policy," he wrote. "While the database was created for genealogical research, it is important that GEDmatch participants understand the possible uses of their DNA, including information of relatives that have committed crimes or were victims of crimes. if you are concerned about non-genealogical uses of your DNA, you should not upload your DNA to the database and/or you should remove DNA that has already been uploaded."

Your family controls your privacy

It's probably safe to assume that Joseph James DeAngelo has never placed any DNA test results online. So how were the police able to identify him?

Because you and your relatives share ancestors, you also share DNA. The fraction will depend on the degree of relatedness; siblings will typically share half of their genomes, while first cousins only share 1/8th. But the pattern of shared DNA is even more telling. We inherit chromosomes, which are large, single molecules of DNA. Over time, these molecules will gradually exchange segments with chromosomes inherited from other individuals. But the process is slow, so long stretches of your ancestors' original chromosomes are preserved intact for many generations.

As a result, the 1/8 of a genome you share with a cousin isn't mixed randomly throughout your chromosomes. Instead, it's found in large chunks that are identical, interspersed with equally large chunks that are unrelated. By identifying these chunks using DNA data, you can estimate the degree of relatedness between any two individuals (if there is any). As people make more of their DNA available through public-facing services, the prospect of identifying other family members there goes up.

This has led to many happy stories of long-lost family members found and the discovery of family members people never knew they had. But it also has the potential to allow people who don't want to be found to be identified—and their reasons for not wanting to be found may be nowhere near as nefarious as DeAngelo's.

DNA testing has reached a level of popularity that ensures that many of us have parts of our genome available online, even if we've never spit into a test tube ourselves. And the decisions on who gets access to that data may be in the hands of family members we've never spoken to—or didn't even know existed. And, once a few family members are identified through DNA, public records can be used to identify other family members, as was done in DeAngelo's case.

“Wonderful tools”

GEDMatch, operated just outside of Palm Beach, Florida, has been around for years, inviting amateur genealogical researchers to upload their raw DNA data to better understand distant family ties. Compared to modern, sophisticated sites like 23andMe, GEDmatch's website is far more basic.

Early on, the site touted:

Have you ever been overwhelmed with your genealogical data, and wished there was some way to pull it all together? Have you ever suspected that you have a relationship with another person, but you couldn't quite find the connection? Maybe the methodical comparisons of a computer can help find a connection you might have missed.

FTDNA's 'Family Finder' DNA test and 23andMe's 'Relative Finder' DNA test are proving to be wonderful tools to help the genealogist find connections with other families. But, sometimes the ancestral connections are not obvious.

The GEDmatch.Com site provides tools for making 'deep' comparisons between genealogies and DNA test results to help identify possible hidden ancestral connections with distant cousins.

Now, the site has a rudimentary privacy policy, which states:

GEDmatch exists to provide DNA and genealogy tools for comparison and research purposes. It is supported entirely by users, volunteers, and researchers. DNA and Genealogical research, by its very nature, requires the sharing of information. Because of that, users participating in this site should expect that their information will be shared with other users.

Earlier on Thursday, some media outlets, including the Sacramento Bee, first reported the Golden State Killer investigation’s link to DNA analysis companies, leading to speculation that more mainstream commercial services might be involved. Ars contacted 23andMe, Ancestry.com, MyHeritage, and Helix—they all denied being connected to the DeAngelo investigation.

"Ancestry advocates for its members’ privacy and will not share any information with law enforcement unless compelled to by valid legal process," Melissa Garrett, an Ancestry.com spokeswoman, emailed Ars in a statement, noting that the company had never shared genetic data with law enforcement.

Similarly, Andy Kill, a spokesman for 23andMe, emailed Ars to say that it was the company’s policy to "resist law enforcement inquiries."

"23andMe has never given customer information to law enforcement officials," he wrote. "Our platform is only available to our customers, and does not support the comparison of genetic data processed by any third party to genetic profiles within our database."

The Sacramento County District Attorney's Office initially declined to provide any further details. "We can confirm that what Sam Stanton from the Bee reported today is accurate. It’s an ongoing investigation," Chief Deputy Steve Grippi told Ars in an emailed statement Thursday evening. "We have given you as much information as we can at this time. No further information on this subject will be provided."

John Timmer contributed reporting.

reader comments

184