More than three years after Louisiana passed a law aimed at getting guns out of the hands of domestic abusers, victim advocates say only the Lafourche Parish Sheriff's Office has systematically taken on the job of following through on that mandate.

In the rest of the state, advocates say little has changed, despite the law on the books that bans people with protective orders against them or those convicted of certain domestic abuse charges from possessing guns. The problem, they said, seems to be that despite prohibiting gun ownership for these offenders, the Louisiana Legislature never set up a system to ensure the firearm is surrendered or taken away.

In Lafourche Parish, a small division of the Sheriff's Office actually started looking at this problem even before Louisiana acted in 2014, relying on an older federal law that says many people with domestic violence convictions — even some convicted of misdemeanors — can't possess a gun.

“Lafourche’s process has been really groundbreaking for our state," said Mariah Wineski, the executive director for the Louisiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence. "They took the initiative to make this a priority. ... What they were able to to do and have been able to do is incredible, and I see no reason why it can’t be replicated."

When someone in Lafourche becomes prohibited from possessing a gun because of a domestic violence offense or protective order, the Sheriff’s Office contacts them. If they acknowledge having firearms, deputies then supervise the transfer of the weapons, either to a qualifying friend or family member, or to the Sheriff's Office.

“We’re concerned about domestic violence and about firearm violence. … We’re not simply going to let someone masquerade and pretend that they’re in compliance with the law,” said Lafourche Parish Sheriff Craig Webre.

Lafourche Parish Sheriff Craig Webre

Webre touts the success of the program, pointing out that his parish of about 100,000 residents has not seen a homicide committed by a prohibited possessor since 2014. He argues ensuring domestic abusers don't have ready access to guns creates a kind of "cooling off" period that limits impulsive firearm use.

State Sen. JP Morrell is now hoping to establish a similar process statewide, a move he said would help ensure the protections provided to domestic violence victims are afforded as the law intended.

“We often hear that we need to tighten the laws that are already on the books. … The bill is just kind of laying out how you do it,” said Morrell, a New Orleans Democrat.

Morrell’s bill, which lays out how to transfer firearms from prohibited possessors but also includes a more stringent framework to identify and penalize those banned from purchasing guns who still try anyway, easily passed the Senate in early April. On Wednesday, it could face more scrutiny in the House criminal justice committee, where similar proposals have died in the past.

No implementation strategy

Louisiana ranks consistently as one of the worst states for the number of women killed by men, according to data from the Violence Policy Center. Based on the latest figures from 2016, Louisiana’s homicide rate for incidents where one woman was killed by one man is almost double the national average, coming in behind only Alaska and Nevada. It is not clear how many of these killings involved domestic partnerships, as no national data set looks solely at domestic-related homicides.

But those numbers stood out to Lafourche officials, especially Lt. Valerie Martinez-Jordan, who runs the sheriff’s social services division. Even before Louisiana lawmakers began addressing the issue of armed domestic abusers, she and Webre looked for ways to better protect victims of domestic violence from further harm — at that time finding prohibitions only in federal laws.

If New Orleans Rep. Helena Moreno succeeds in her latest attempt to update the state’s domestic violence law, she may very well have to thank …

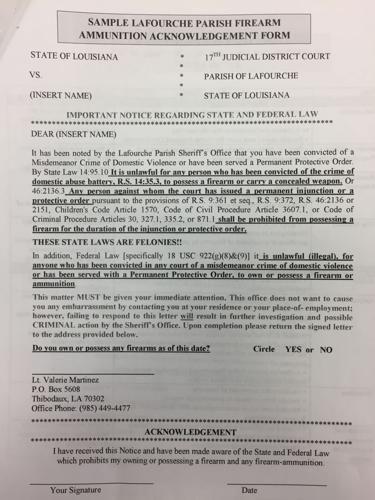

Martinez-Jordan, whom Webre called the “architect” of the gun transfer program, collaborated with local Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearm and Explosives agents to craft a letter to inform those deemed ineligible under federal law to possess guns. When she started that process 2010, Martinez-Jordan said it was primarily educational, alerting people of the laws they might be violating in hopes they would comply because deputies did not have jurisdiction to arrest or prosecute under federal statutes.

“The federal law that (started) this whole concept of gun divestiture, there was never an implementation strategy,” Webre said. “They should have set the process in motion. So the states, ultimately … started enacting their own version of federal law.”

Louisiana's law, adopted in 2014, prohibits firearm possession for a person convicted of domestic abuse battery for 10 years after the completion of a sentence or probation. It also bans guns from someone with a protective order against them, whom a judge has found is a potential threat to the physical safety of a family member, household member or dating partner. That restriction is in effect only while the order is in force, typically 18 months.

Once the Legislature tweaked the law, Martinez-Jordan saw an opportunity to expand, and actually enforce, her firearm divestment process.

With support from the local courts and the District Attorney’s Office, the Lafourche Sheriff’s Office receives notification when a person loses eligibility to possess a gun due to a conviction or protective order. Upon notification, deputies flag the person in their internal database so deputies — and other local law enforcement officers — can be aware of the restrictions during a possible interaction. Martinez-Jordan's office also sends a letter explaining the laws that prohibit the person’s gun possession.

The majority of recipients return the letters, Martinez-Jordan said, signing that they understand the restrictions and indicating whether they possess guns. Anybody who doesn't respond, as well as people who acknowledge their gun ownership, receive follow-up visits from trained deputies.

For the gun owners, deputies explain the three options they have to transfer their weapons: hand them over to a qualified third-party recipient for storage; sell or donate the gun indefinitely; or give the gun to the Sheriff’s Office for safe keeping.

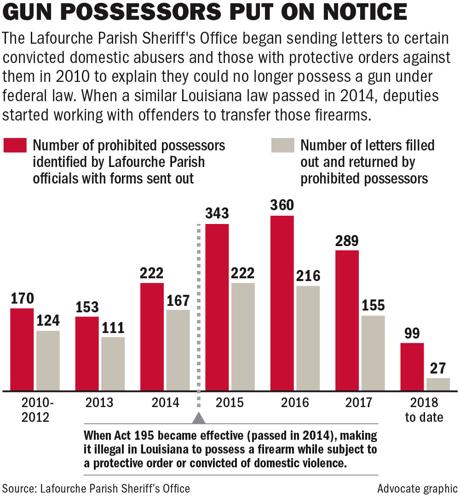

Since 2015, when the state law became effective, the Sheriff’s Office has sent out more than 1,000 such letters, of which more than 55 percent have been returned. When guns were discovered, either by the letters or in follow-up visits, the majority of prohibited possessors have turned the weapons over to third parties, Martinez-Jordan said, though the exact number of those transfers was not immediately available. As of October, the Sheriff's Office was storing 13 guns from the transfer process.

“To be able to implement the intent and the spirit of that law, it’s given assurance to victims that we’ve done everything, that we care about them,” Webre said.

Although Webre and other advocates of this kind of system admit it’s not foolproof — somebody who hands a gun over to a relative or friend might be able to easily get it back — they contend it’s the best out there. The process is modeled off similar successful processes in Wisconsin and King County, Washington.

“There are obvious gaps … (but) it doesn’t mean we should be making it easy for them,” Wineski said. “We do think it’s a really workable process.”

At a recent Louisiana Sheriffs' Association meeting, about 10 of the 35 sheriffs there said they had, in some capacity, taken guns away from people deemed a prohibited possessor though the courts, either from a domestic violence conviction or protective order, said Michael Ranatza, executive director of the group. He said that often happens when deputies were called for another reason, like a domestic incident or traffic issue, and a gun was found with someone who is restricted under the law.

The Louisiana Legislature backed several bills Tuesday that seek to provide additional layers of protection for domestic violence victims.

“It doesn't mean that other sheriffs are not doing it; it means Sheriff Webre has a more formal program,” Ranatza said. “He has been very proactive in working with his judges and other entities, and I certainly give credit where credit is due. … We’re very proud of what he’s done.”

In an Orleans Parish civil courtroom, Judge Bernadette D’Souza also has worked to implement the applicable portion of the 2014 law since it was passed, saying she believes “it’s incumbent on me to keep that family safe.” D'Souza doesn't deal with criminal cases, only family court proceedings that could result in a protective order.

The law requires, upon finding the subject of a protective order presents a “credible threat to the physical safety of a family member or household member,” that a judge must explain to the person that he or she is prohibited from possessing a firearm during the period of the order.

D’Souza goes a step further when guns have been mentioned in a victim’s testimony or complaint, working with Orleans Parish sheriff’s deputies to fulfill her court order that guns must be transferred from the possessor. She said the Sheriff’s Office will store the guns until the end of the protective order, when she will, after an evaluation, file a second court order to return the guns.

"I believe it’s at my discretion,” D’Souza said. "If I am to hear testimony of a witness where the defendant held a gun to her head, am I supposed to let the defendant walk away?"

'Closes the gap'

Morrell’s proposal, Senate Bill 231, would make sheriffs' offices the agencies in charge of overseeing gun transfer programs, while laying out how they should move forward with this responsibility.

“We passed the requirement to transfer guns (from certain domestic abusers) … but they didn’t create a mechanism as to how to do it,” Morrell said.

Under the bill, judges would issue a court order for the transfer of firearms and suspension of concealed handgun permits after a qualifying conviction or the filing of a protective order.

The person would then have 48 hours to transfer their guns, under the supervision of a local deputy, through one of the three options used in Lafourche Parish. They also have five days to file paperwork with the clerk of court proving the transfer or declaring that they don’t have guns.

When a person regains their gun possession rights — at the end of a protective order or 10 years after a completed sentence or probation period for a domestic abuse conviction — the sheriff would return any guns they stored. The bill allows sheriffs' offices to charge a fee for weapon storage.

Morrell’s bill also includes language to strengthen penalties for prohibited possessors who try to purchase a gun despite the legal restrictions, and it would require firearm dealers who determine someone tried to purchase while prohibited to notify law enforcement, as well as a mandate that victims also are informed.

Ranatza said the Louisiana Sheriffs' Association overall supports the bill but wants to clarify certain details, like how judges can expedite determining if a newly prohibited possessor has weapons, how firearms would be returned at the end of the prohibited period and how to address financial constraints.

“We’re very much interested in assisting Sen. Morrell in the passage of this very important legislation,” said Ranatza.“(But) we still have some concerns. … We’re only trying to make the process better.”

Before the Senate passed the bill, the National Rifle Association sent out an alert against it, highlighting the penalty for firearm dealers if they do not tell law enforcement of an attempted gun purchase by a prohibited possessor. Although multiple NRA spokespeople did not return calls for comment this week, Morrell said the group has moved to a neutral position on the bill, which no longer includes criminal penalties against gun dealers who fail to communicate with police.

Morrell said he is well aware that any bill restricting Second Amendment rights can become controversial, but he and anti-domestic violence advocates remain hopeful the House will join the Senate in its passage.

“(The bill) essentially closes the gap between our existing domestic violence laws and their actual meaningful implementation in our state,” Wineski said. “We have every hope and every reason to believe that with the passage of the law, we will be able to save lives in Louisiana.”