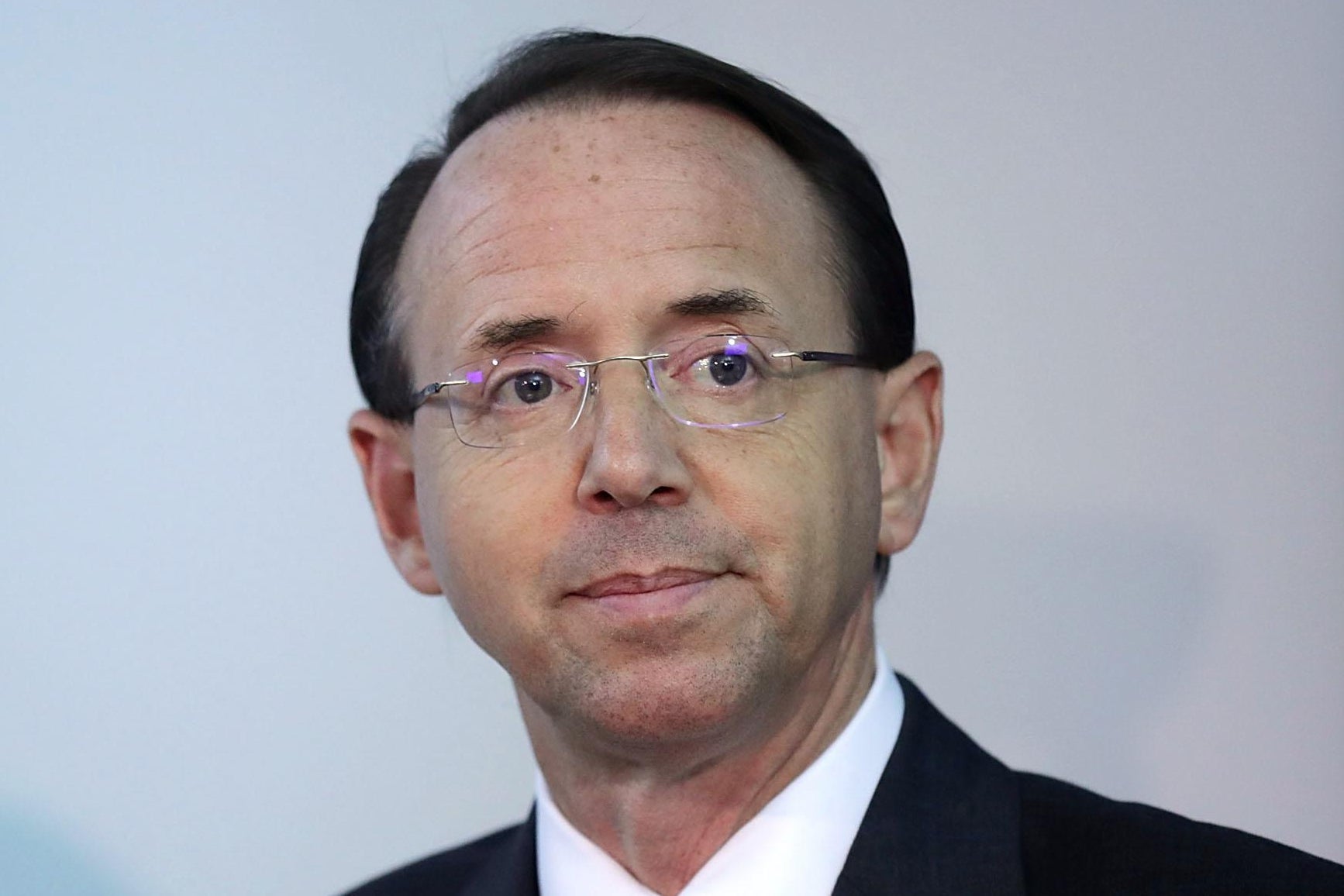

In a blockbuster story in Friday’s New York Times, Adam Goldman and Michael S. Schmidt reported that Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein suggested covertly recording President Donald Trump’s conversations in 2017. According to the story, Rosenstein also suggested that people at the FBI interviewing with Trump to be the bureau’s director could also record him. Of course, Trump needed a new FBI director after firing James Comey on May 9. Rosenstein reportedly made his suggestions in two meetings while behaving “erratically” in the following days, which the story calls “disorienting.” The story also reports that Rosenstein discussed invoking the 25th Amendment, which would have the Cabinet remove Trump from office.

The piece has drawn widespread attention, in part due to Rosenstein’s vehement denial to the paper and to broad fears that Trump would fire Rosenstein over the story, ultimately impairing special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia probe, which Rosenstein oversees. The Times story does not quote directly from anyone who attended either meeting, but it does note that the reporters spoke with people who were briefed on the conversations or on memos that arose out of them, including ones written by Andrew McCabe, the then–acting FBI director who was later fired.

The Washington Post and others have followed up on the Times’ reporting, with the Post quoting one person who suggested that a Rosenstein comment on recordings was meant sarcastically. In the Times piece, the reporters write that a person present at one of the meetings—via a statement provided by the Justice Department—acknowledged Rosenstein’s remark about wearing a wire “but said Mr. Rosenstein made it sarcastically.” (The Times spoke to others who “confirmed that he was serious about the idea.”)

On Saturday, the paper’s deputy managing editor, Matt Purdy, defended the story on Twitter. “The DOJ claim that Rosenstein was sarcastic when he suggested he wear a wire on Trump is not supported by our reporting or others. If you actually read them, the follow stories by the Wapo, ABCNews and CNN support our story, not debunk it,” he wrote.

I recently spoke by phone with Schmidt, a Washington correspondent for the Times. During our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, we discussed how the Times treats sourcing, the state of Trump and Rosenstein’s relationship, and the differing accounts of some potentially very important meetings.

Isaac Chotiner: You guys are talking about two separate meetings. Is that fair to say?

Michael S. Schmidt: Yeah, the separate conversations, or yeah, separate meetings that occurred between Rosenstein, that McCabe was involved in.

And these were around May 15, 2017?

Yeah, so this is an incredibly important period of time that has not received a lot of attention. It’s the eight days between the Comey firing and the appointment of Mueller, and where Rosenstein is sort of thrust to the front of the national stage and has to figure out what to do.

OK. You and Goldman write, “Several people described the episodes in interviews over the past several months, insisting on anonymity to discuss internal deliberations. The people were briefed either on the events themselves or on memos written by F.B.I. officials.” So does this mean you didn’t get anything from anyone in the room? That this is all based on either secondhand accounts—people who were in the room told these people you spoke to—or in a way, thirdhand, which is from the memos?

I wouldn’t assume that. I would say that we took the sourcing as far as we could take it, and sometimes if you’re more specific in sourcing incidents, you get concerned that you could jeopardize a source. So it’s a balancing act between how much you can show the reader and how much you need to protect someone, and just in general, that’s the decision we have to make all the time. So I would just say that we took the sourcing as far as we could.

And actually, I would point out that there is at least one person in the story who was in the room, and that was the handout from the Justice Department that was given to us. An anonymous person—not anonymous to us, but a person on background—who described the events of the story. Our reporting did not show—did not give a lot of credibility to the Justice Department pushback.

Why were you so doubtful about that person, and was it a hard decision to run with the story given that the only person whom you can identify even on background, who was actually in the room, offered a contradictory account?

Well, the interactions in the room are documented in ways that go further beyond people’s memories: memos and notes that were taken at the FBI after those interactions. And you are in the balancing act of looking at “OK, are we going to take someone’s recollection? Are we going to lean into that, or are we going to lean into what a memo may say, or what notes may say, or the recollections of others who have more detail and offer more specifics than what the person in the room is giving to us?”

Just because you’re in the room, and you offer one detail, does not necessarily mean that you’re telling the truth or it’s accurate. A memo, or notes, or a much more detailed memory of someone who may not have been in the room, may be much better.

Were you doubtful of the Justice Department giving you this person to offer a differing account because the memos and other things disputed that account? Or was it because you guys felt like the credibility of the Justice Department—which obviously had a vested interest in this—meant that you trusted it less? Or is it both?

No, it’s much more the former. The depth and breadth of our reporting led us to a different conclusion than what the Justice Department had given us.

Some people have criticized the story by saying things like, “If you’re relying on something like a memo, it may not pick up something like sarcasm.” And there is one quote in the Washington Post story that has Rosenstein saying to McCabe, “What do you want to do, Andy, wire the president?” Was that something that you wrestled with when you were working on the story, and how did you deal with that possibility?

This story has taken us months, if not a year, to get to the bottom of, and that’s because the people who had access to this information knew what had gone on and knew it wasn’t a joke, and wouldn’t talk to us about it. If this was a joke, we don’t think it would have been so difficult for us to have worked to get to this information. If this was a joke, this would not have been memorialized, documented, and discussed in the FBI in the way that it was. If this was a joke, Rod Rosenstein probably wouldn’t have made it more than once. Also, if this was a joke, the other thing is, this 25th Amendment stuff is in a memo as well. So this is like—is this a broader conspiracy of jokes that was going on?

The Post story states, “People familiar with the 2017 discussions—and the memos written about the discussions—offered wildly divergent accounts of what was said and what was meant.” Was this something that you guys also noticed in your reporting, separately from the person whom the Justice Department put out?

I would say that the reporting on these interactions fell into two buckets. There was one background source from the Justice Department who said one thing in one bucket, and then there was a much larger breadth of reporting in another bucket that included many more folks and many more details, and when we looked at these buckets, we said, “Hmm, well here’s one bucket that has one person in it, that was given to us by the Justice Department after we approached them on this, and here’s another bucket with a lot of folks whom we’ve talked to, folks who have been reliable, folks who we believe are telling the truth, folks who were very difficult to get to tell us about this, and there’s many more of them, so OK. So what are you going to choose?”

When you’re writing a story like this, how concerned are you that your sources have axes to grind, and how conscious or concerned about this were your editors?

Obviously, everyone has their own perspective, their own gripes, their own biases when they talk to us. We consider that every day, on a daily basis, in looking at how we assess all of this information, and it’s baked into every decision that we make. And in this era, we’re forced to make dozens of [those decisions] a day, if not hundreds a week, and that’s just part of the calculation that we look at.

What I will say does bother me in this era is an idea that’s pushed by both the left and the right—both cable-news left folks and cable-news right folks—that the media is, or reporters are just sort of these lemmings that sit at their desk and get quote-unquote “leaks,” where folks call us up and leak us information, and one side is covertly, surreptitiously trying to use us to undermine the other. This is something that is constantly pushed and has been constantly described, including about this story—that these are leaks of folks using us.

And I understand why this takes hold, because people can’t see the names of the sources that we use, and when they see that, they have doubts, but an enormous percentage—80 to 90 percent of the stuff that we end up writing about—is because we have gone out and sought out folks to find out what’s going on. You know, it doesn’t come the other way.

There’s been a lot going on in the Mueller investigation in the past month or so, involving Michael Cohen, Paul Manafort, declassifications, and nondeclassifications. Do you think your breakthrough may have had something to do with the fact that, for whatever reason, people were more willing to talk based on various things going on in the news, based on the political calendar, or based on other considerations like that?

I think that, since the day Donald Trump took office, folks ranging from law enforcement to political appointees to career officials have been unnerved by the president and are more willing to talk. And we have seen that throughout the entire presidency. I have not seen that go up or down. I’ve seen that be pretty steady.

To circle back to the thing you said after I asked about your sources being several people who were familiar with the conversations: I think the average reader will think, about your story, “OK, well if he says ‘several people familiar with the memos,’ that is a guarantee that he didn’t talk to anyone in the room.” It seems like you’re saying that that’s not the case, and that’s one of the ways you have to protect sourcing. But is that something that journalists should be thinking or worried about?

Anonymity is really, really difficult for us, because, as I was saying, people get immediately skeptical of it, and it’s very hard for us to show all of our homework, and show all of the work, and who the folks were, and how they knew everything. It’s a really, really tough balancing act, and I get why readers don’t love it. The problem is that it’s our best, and maybe it’s our greatest, tool to do what we do. And in this era, we have to be heavily reliant on it. And readers hate it when they see anonymous sources, but they almost always end up really wanting to know what they have to say, because they know that that information is a more unvarnished view of what’s going on, and in any time, or especially this time, people really want that, and you need that tool to get at the facts.

Explaining how that works is difficult, but if we’re out there in settings like this, talking about it and trying to explain the process, as Woodward did when his book came out, and such, and I think the more that we do that, the better.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Trump and Rosenstein had had a bad relationship for a while, but it had actually gotten better in the past several months. Do you have any sense of what their relationship is like now?

I think Rosenstein’s done a very good job of trying to balance running an investigation into the president and not being fired by him. And that is something that, my guess [is], he’s focused on every day, trying to strike that balance, and that’s pretty hard. And so far, he’s survived.

I think a lot of people are really anxious right now, and I think that colored some of the response to the story. I also think some people are angry with the Times for various things, going back to the Hillary Clinton email coverage, going back to the Oct. 31, 2016, story “Investigating Donald Trump, F.B.I. Sees No Clear Link to Russia.”

Well, if we’re out there following the story, without fear of favor, and making our best judgments on a daily basis—we’re a daily newspaper—we’re not going to have a lot of friends, and we didn’t get into this to have friends or allies. We’re just out there, just trying to cover things. And that’s a hard concept for folks to understand and wrap their minds around in such a politically charged environment, but we believe that our independence, and our unbiased approach to rooting out the facts, is an incredible contribution to what’s going on, and we just try to do that on a daily basis.