The Inside Tale of Colin O’Brady’s Death-Defying, Record-Breaking Antarctic Crossing

On November 3, Colin O’Brady stood alone on Antarctica’s Ronne Ice Shelf, surrounded by nothing but endless, blinding white. The engine growl of the plane that had left him at the edge of the continent faded into silence.

At 33, the boyish, Portland-based adventurer was already a world-class triathlete. Two years earlier he’d set a speed record for climbing the highest peak on every continent and reaching both poles in just 139 days. Already in 2018, he’d skied across Greenland and set another speed record for reaching the highest points in all 50 states.

But this was different. O’Brady was about to attempt the first solo, unsupported ski crossing of the coldest, highest, most remote continent on Earth. His goal, the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf on the opposite side of Antarctica, was more than 900 miles away. It was the same journey that killed English Special Forces veteran and polar explorer Henry Worsley in his attempt just two years prior.

Before he took his first step, O’Brady bent down to cinch a strap on the 375-pound sled he would haul across the frozen waste.

The strap’s clip snapped. “All I could do was laugh,” wrote O’Brady in a social media post days later.

An hour later, the effort of pulling a load twice his own weight through negative-27-degree Fahrenheit temperatures (plus windchill) had reduced O’Brady to tears. Salty ice coated the inside of his goggles. He made a satellite call to his wife and expedition manager, Jenna Besaw, who was monitoring his progress via GPS from their apartment in Northwest Portland. She had helped come up with a name for the project: The Impossible First.

“We may have called it the right thing,” O’Brady told her.

Image: Courtesy Colin O'Brady

Besaw talked him off the ledge and persuaded him to push on to his planned route’s first waypoint, a half mile from the start. O’Brady made it and collapsed inside his bright red tent, his mind still full of doubt.

“That was one of the hardest days of all,” he says. “The strain and magnitude of the entire thing just really hit me.”

Over the next two months, O’Brady would draw on years of physical and mental conditioning as a world-class endurance athlete to weather the trek. But, oddly enough, it may have been the benefits of growing up in a liberal city where nutrition, wellness, and outdoor adventure are a way of life that got him across the finish line.

O'Brady’s mother, Eileen Brady, is arguably better known than her son in local circles: She’s a cofounder of upscale homegrown grocery chain New Seasons. She and her then-husband, organic farmer Tim O’Connor, came to Portland in the mid-1980s from the crunchy-activist world of Olympia, Washington, to raise O’Brady and his older sister.

O’Brady grew up swimming at Creston Pool, hiking in the Columbia River Gorge, and skiing on Mount Hood. His mother read him The Way of the Peaceful Warrior while his father, an Eagle Scout, took him on his first climbs up Three Fingered Jack and South Sister.

Natural foods were a tentpole of family life; both of O’Brady’s parents worked at Nature’s Fresh Northwest, a grocery chain acquired by Wild Oats in 1999. As a teen, O’Brady remembers helping his mother pick a name for a new grocery store that would focus on local and organic products, and what kinds of items it would

carry. “That was just normal dinner-table conversation,” he says. The first New Seasons opened in Raleigh Hills in 2000.

At Lincoln High School, O’Brady won state championships in swimming and soccer, and when he graduated in 2002 he was recruited to swim at Yale. After

college, he proceeded to bike from Connecticut to Oregon to raise money for Habitat for Humanity. His next venture, a round-the-world trip (O’Brady painted houses for five years to pay for the tour), ended abruptly in 2008 on the island of Ko Tao in Thailand. There, a freak accident with a flaming jump rope left him with second- and third-degree burns covering 25 percent of his body, mostly on his legs and feet. He underwent eight surgeries, and was told he might never walk again.

In his room at the Legacy Oregon Burn Center, O’Brady grappled with what a future in a wheelchair might look like. “It was like so much of my identity had been taken away from me,” he says. With his mother’s encouragement, he set himself an ambitious recovery goal of racing in a triathlon. A year and a half after his accident, he entered his first—and won, beating out almost 5,000 competitors in the amateur division of the Chicago Triathlon. “I surprised the heck out of myself,” he says. The following day, he quit his job in Chicago finance and flew to Australia to start training for triathlons full time.

For the next six years, O’Brady raced on six continents as a member of the US national triathlon team. Part of his unorthodox training was going on 10-day silent meditation retreats at places like the Northwest Vipassana Center in Washington. Spending 12 hours at a time learning to calm his thoughts helped during long, punishing races. It would serve him well during his two-month-long traverse of Antarctica—a landscape of total sensory deprivation and extreme weather.

Image: Courtesy Colin O'Brady

In 2015, O’Brady retired from triathlon to focus on climbing and exploring. “[Racing professionally] got to a point where it felt kind of self-serving, just keeping my sponsors happy.” He wanted to aim higher, in both his achievements and the impact they had on the world.

Besaw, by then his fiancée, had helped his mother organize a run for Portland mayor in 2012. Now she helped O’Brady decide on a headline-worthy goal: the speed record for the Explorers Grand Slam—climbing the highest peak on every continent and skiing to both poles.

In April 2016, four months into his attempt, O’Brady’s broadcast from the summit of Everest—the first-ever Snapchat from the world’s tallest peak—drew 22 million views. “I hope it gave people a window into a place they don’t normally go,” O’Brady says. By climbing Denali in three days instead of three weeks, he demolished the Grand Slam record.

At that point O’Brady could have just written an inspirational book or two and coasted on lucrative corporate speaking gigs for the rest of his life. His story—accident, recovery, world-record triumph—is practically a Tony Robbins seminar. His 2017 TEDx talk, titled “Change Your Mindset and Achieve Anything,” has almost 1.5 million views on YouTube.

But O’Brady wasn’t done. The next frontier held an achievement that wasn’t just epic and easily grasped by the average media consumer, but something no one had done before—something that would pit him against himself. “I wanted to see what the limits of my capacity were,” he says.

It was a short list, and at the top was a feat that had eluded war-hardened polar explorers for over a century: crossing Antarctica alone, without resupply points, on human-powered steam.

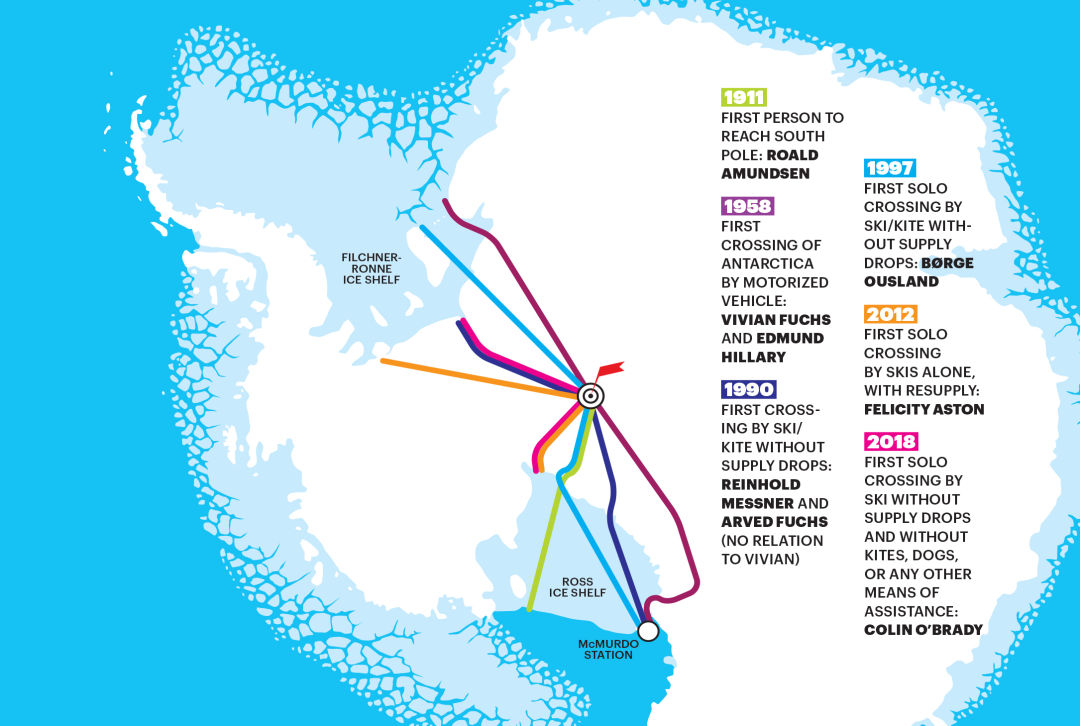

Ever since Norway’s Roald Amundsen first reached the South Pole in 1911, adventurers have dreamed of crossing the continent in a single go. English explorer Ernest Shackleton’s famous multiyear survival story started as an attempt to cross Antarctica by foot in 1915. (He considered the crossing “the last great Polar journey that can be made.”) In 1958, five years after Edmund Hillary summited Everest, the New Zealander helped drive specially adapted tractors across Antarctica by way of the South Pole.

Norwegian Børge Ousland made the first solo crossing of Antarctica in 1996–97, kite-skiing to travel 1,768 miles in 64 days. In 2016, Henry Worsley made it over 900 miles on just skis in 71 days when he had to be airlifted out, exhausted and sick. He died of bacterial peritonitis, a serious abdominal infection, in a hospital in Chile.

Nobody had yet checked all the boxes: cross the continent alone, without resupply, using nothing but muscle power. To O’Brady, it was the perfect challenge.

O’Brady knew he’d have to train differently than before. He enlisted the help of Mike McCastle, a Portland-based performance coach and former navy petty officer. The soft-spoken trainer, who resembles an action-figure version of Jordan Peele, holds four world records himself, including completing 5,804 pull-ups in 24 hours while wearing 30 pounds of weights, and finishing a rope climb equal to the height of Mount Everest in under 27 hours. He once pulled a Ford F-150 pickup 22 miles across Death Valley in 19 hours. They’re all part of what he calls his 12 Labors Project, to raise money for wounded veterans and for cancer and Parkinson’s research.

Starting in March 2018, McCastle and O’Brady worked together three times a week. “Colin is probably one of the most adaptable athletes I’ve worked with,” McCastle says. On top of the raw materials of fitness, discipline, and commitment, O’Brady brought something else: consistency. “He can do the basic, mundane things very well.” In Antarctica’s extreme conditions, simple tasks like lighting a stove or clipping into a ski can mean the difference between life and death. Tension and fatigue erode coordination and cognition; tunnel vision sets in, memory slips, fingers fumble.

McCastle’s challenge was to replicate as closely as possible the stressful situations O’Brady would encounter on the ice, teaching him skills to stay focused enough to do what he had to do to survive. He also drew from his experience with Parkinson’s patients, who can struggle with the loss of fine motor skills.

The training regimen included enough standard weight lifting to help O’Brady gain 20 pounds of muscle. But it also involved tasks like making him tie knots after holding a plank position for a full minute with his hands in ice water. O’Brady describes another exercise that started with a hard weight-lifting circuit and ended with him in a chair position against a wall. “Then Mike puts a weight plate in my lap, pulls out a little Lego set and says, ‘You can’t get up until you build this.’”

The creative training continued through 2018, during which O’Brady also did his shakedown ski crossing of Greenland and climbed the highest peak in every US state in 21 days, 9 hours, and 48 minutes, smashing the previous record by three weeks.

More help came from Dixie Dansercoer, a Belgian explorer with numerous record-setting polar expeditions on his résumé. Dansercoer, who has a house two hours from Portland in Oceanside, crossed Antarctica with a partner in 1997–1998 using skis and kites. Ten years later, the pair made the first-ever crossing on foot from Siberia to Greenland via the North Pole.

When O’Brady approached Dansercoer for advice, the Belgian told him: “I think you’re the person to do it, but you’re missing some basics.” He taught O’Brady tricks like a more efficient way to walk when pulling a sled on ropes: a normal stride creates a jerking motion, so “you need to walk like a duck, sink a little deeper with the quads, like a human shock absorber.”

Dansercoer agreed with McCastle that mind-set is critical. “The mental side should take up 80 percent of your training time,” Dansercoer says. “It involves self-knowledge, humility, analyzing your weaknesses. It’s in the moments where everything collapses—you, your equipment, the weather, communications—when it can slide downhill very quickly.”

Above all, he says, “nutrition is the key to success. There’s no way around it.”

On top of the superhuman endurance, strength, and willpower needed to tackle Antarctica, would-be crossers have to wrestle with a simple calculation: given the massive energy expenditures polar travel requires—up to 10,000 calories in a single day—how much food can you haul before it becomes impossible to pull, and how far can it take you?

Early explorers left caches of food for return journeys and dined on sled dogs when things went south. Modern explorers can have supplies dropped by plane ahead of time. Those who go the unsupported route often find nutrition is the limiting factor. As one Wired article put it, “it’s straight-up impossible to take enough calories with you to get across the continent of Antarctica.”

“As I evaluated the others who had attempted and ultimately failed the crossing,” O’Brady says, “I was like, where do people get it wrong?” From the usual trail mix and oatmeal to (in the case of Worsley, by some reports) heavy luxuries like cigars and whiskey, the answer was food.

O’Brady’s upbringing in the bosom of the natural food industry steered him in the direction of a whole foods supplement company called Standard Process, which had just opened a clinical research facility at its North Carolina headquarters. “We found we were speaking the same language around health and wellness,” O’Brady says.

Starting last March, the company’s researchers put O’Brady through a year-long study worthy of an astronaut: treadmills, allergy tests, body fat measurements, and more than 300 blood tests. The result was the Colin Bar, a 100 percent unrefined, unprocessed food bar specially designed for O’Brady’s personal physiology and the demands of the Antarctic crossing. Each 7.5 oz bar packed in 1,100 calories of cashew butter, rolled oats, dried cranberries, and a high percentage of coconut oil to keep them from turning into frozen bricks.

Image: Courtesy Colin O'Brady

When O’Brady set off for that first waypoint on the Ronne Ice Shelf, his sled was packed with 250 pounds of food and stove fuel. Aside from that, he carried the barest of essentials: his tent, sleeping bag, ski gear, GPS, and satellite phone, as well as a few repair tools, a backup stove, and an extra ski pole and ski binding. “I didn’t even have an extra pair of underwear,” he says.

A mile away, English explorer Louis Rudd was setting off on a solo crossing of his own. The British Army captain, a close friend of Worsley, was 16 years older than O’Brady and had more experience in polar travel. The simultaneous start was the result of a narrow weather window and the complex logistics of polar travel, O’Brady says, even though media accounts pumped up the “race” narrative. Both men had the option of calling for a rescue by solar-powered satellite phones, if necessary. Otherwise, each was on his own.

O’Brady’s days quickly took on an almost hypnotic rhythm. At this time of year, when the sun never set and whiteout conditions reduced the field of view to just his compass, O’Brady drew on his Vipassana meditation training to endure hours on end of sensory deprivation. He listened to podcasts from self-betterment gurus like Rich Roll and Lewis Howes, music (Paul Simon’s Graceland on repeat), or simply ran silent.

For water, O’Brady melted six liters of Antarctic snow every day. Breakfast was a special blend of oatmeal with added fat and protein, also courtesy of Standard Process. Then came 12 hours of sled-pulling, fueled by 100-calorie chunks of Colin Bars every 15 to 40 minutes. A lunch of ramen in the middle of the day provided a hit of warmth and salt. After stopping around 8 p.m., O’Brady set up his tent and made dinner: a protein powder drink, chicken noodle soup, and a freeze-dried dinner. After downing the last of 7,000 daily calories, he crawled into his sleeping bag, checked in with Besaw, uploaded an Instagram post for his 157,000 followers, and fell asleep under the glow of the midnight sun.

That’s if everything went smoothly. Storms swept in with 50 mph gusts, reducing visibility even further. Broken terrain often slowed progress to a crawl. On day 27, O’Brady was struggling through an area of huge sastrugis, wave-like snow ridges carved by wind—“it was like pulling the sled over a mogul slope”—when a whiteout storm descended. Three miles into the day, O’Brady took a bad fall and tore the traction aid off one of his skis, forcing him to take his first rest day of the expedition, having gone only 3.5 miles.

Image: Courtesy Colin O'Brady

By the time he made it to the pole on day 40, 556 miles from the start, O’Brady had established a solid lead over Rudd. From here it was all downhill, literally: the pole peaks at 9,307 feet. For safety, he followed the South Pole Traverse, a marked and graded ice track used to drive supplies to the South Pole, for more than 300 miles.

But the worst part of the journey was still ahead. Five days of terrible weather set in around day 44. “One day of a ground blizzard is hard,” he says. “Five days when you’re already so depleted really pushes you to the breaking point. I didn’t know if I could make it.” He had to re-ration his dwindling food—down to only 6,100 calories for a few days—and had developed the early stages of frost nip on his cheek and nose. The South Pole Traverse turned out to be a deeply furrowed surface mostly covered in soft windblown snow, terrible for skiing.

On day 52, O’Brady could see the tops of the Transantarctic Mountains, his first landscape feature in 34 days. The next morning was Christmas. At his usual pace it would take another three or four days to finish. But as he started to ski down the Leverett Glacier, he felt himself slip into what he calls “a deep flow state,” a kind of mental and physical sweet spot. “The weather was terrible, but I got to a place in my mind of complete peace. I started to wonder if I could finish in two big pushes. Then I thought: what if I just didn’t stop?”

Back home, Brady and Besaw watched his GPS track hit 20 miles, 30, then 40, his longest day yet. He kept going past midnight. On a satellite phone call, his wife and mother tried to figure out if he was still thinking rationally, or if he was so spent and exhausted that he was delusional.

O’Brady covered the final 77.5-mile stretch in a single 32-hour push, an effort with few parallels in modern polar exploration. On December 27, 54 days and 932 miles after setting out, he arrived at a wooden post that marked the edge of the Antarctic landmass and the start of the Ross Ice Shelf. He called Besaw and burst into tears. Two days later he welcomed an exhausted Rudd. The English explorer, who relied on more traditional expedition food, had lost 17 percent of his body weight, compared to O’Brady’s 10 percent.

Image: Courtesy Colin O'Brady

“What [O’Brady] did was truly remarkable,” Rudd wrote on his website later. “I pushed hard and skied longer hours and greater distances than I ever have on any previous expeditions, and yet he was still able to finish two days ahead of me.”

O’Brady returned to Oregon in astonishingly excellent health, according to doctors who examined him. Requests for interviews have come pouring in—more than 1,000 at last count—despite a perhaps inevitable touch of controversy about his record-setting claims (see previous page).

There will be more expeditions in the future, he says. After all, pushing his limits and sharing the experience, online and in person, is what he’s best at. “I’ve started to think about myself less as an athlete and more as a performance artist,” he says. “My canvas is endurance sports.”

Image: Courtesy Colin O'Brady

Closer Look: What Counts as a First?

While most of O’Brady’s Impossible First coverage has been positive, there has been some pushback against his claim of crossing the entire continent unassisted. Shortly after the expedition, Antarctic explorer Damien Gildea published an opinionated report on ExplorersWeb pointing out that O’Brady’s start and finish points were both at the (ice-buried) edge of the Antarctic landmass, far from where each ice shelf met the ocean. This made his route significantly shorter than those of earlier explorers like Roald Amundsen and Børge Ousland, who started and finished at the water’s edge. Gildea also contends that following the established South Pole Traverse route made the journey out from the South Pole easier, undermining the idea of a completely unassisted crossing.

Editor's Note: A lengthy feature in National Geographic published in February 2020 digs deep into O'Brady's claims, speaking with several experts and explorers who took umbrage with O'Brady's book, The Impossible First, which came out in January 2020.

In response, O’Brady says he picked the route for safety—the risk of falling into crevasses is less than on alternate routes. “Coming home alive is more

important than anything else,” he says, adding that, if anything, skiing on the furrowed track was slower and more difficult than an alternative route might have been. (In a statement on his website, fellow 2018 crosser Louis Rudd agreed with both points.)

What nobody disputes is that O’Brady and Rudd both did something extraordinary. “Any criticism should have come beforehand,” says explorer Dixie Dansercoer. “The controversy has nothing to do with the feat itself.”