Wot I Think: Metal Gear Solid V - The Phantom Pain

Boss battles

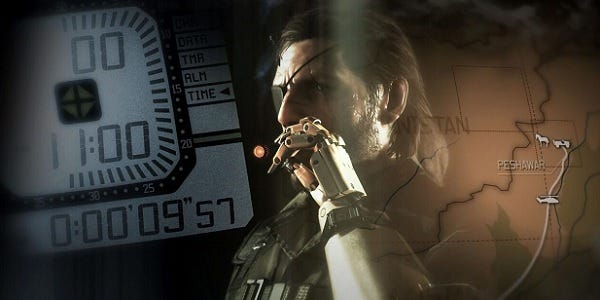

Like Snake with the open expanse of Soviet-occupied Afghanistan stretching out before him, we've got a lot of ground to cover. Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain [official site] is a massive game, both in terms of the systems that drive it and the number of plot threads it feels obligated to weave together. This breadth is the game's triumph, as well as its downfall. The Phantom Pain is the best stealth-action game ever made, and one of the worst Metal Gear stories ever told.

There are two distinct narratives here. One is more easily accessible for those unfamiliar with the series. It's the story of a legendary soldier building a private army to track down a villain and save the world from his secret weapon. Behind that plot is an attempt to fuse together over 25 years of often nonsensical Metal Gear lore.

This is a series which has previously featured a man who shoots bees out of his mouth, a seemingly-immortal shirtless villain named "Vamp", and more retcons than almost any comic book continuity in existence. But here's the thing: I still invested in and actively enjoyed all of that - until now. To go into specifics would entail spoilers, but take it from me, a die-hard Metal Gear fan, that The Phantom Pain is where the series jumps the shark.

It's not just the narrative content that is nonsense, but often the way it's actually told. Snake (AKA "Venom Snake", AKA "Big Boss", AKA Jack, AKA John...are you still with me?) remains oddly mute for many of the game's pivotal dramatic moments. Characters continue to talk at him as though they've heard his imaginary responses, and nothing about the dramatic glances Snake returns make these cutscenes any less awkward. It's bizarre, in a way that does not feel intentionally Metal Gear.

And yet, for a Metal Gear game, these cutscenes are surprisingly rare. In a way, it's refreshing; rarely does The Phantom Pain's narrative interrupt your stealthy sorties. Much of the characters' lengthy exposition has been relegated to optional cassette tapes, which you can listen to while crawling on your belly through the underbrush. But this delivery from the backseat also results in a disjointed plot, the overt complexity of which does not benefit from this structure.

Dramatic pacing is shot to hell, too: the story moves along like a learner driver's first time behind the wheel, alternately slamming the accelerator and brake every few seconds. The Phantom Pain's less-linear, mission-based structure is responsible. You're tugging at multiple plot threads at once, with dramatic revelations repeatedly interrupted by your need to constantly exfiltrate from one mission and redeploy via chopper to the next.

Once your boots have touched the ground and your helicopter departs, leaving you vulnerable in a vast, open, and hostile world, The Phantom Pain offers a transcendent experience. While the game's plot collapses under the weight of 25 years of canon, the stealth systems at play are the result of just as many years of experimentation and refinement. You've seen many of these systems before, both in Metal Gear and in other open world games, but never before have they coalesced with such polish and purpose as they do here. Light and shadow, camouflage and stance, guards who get suspicious if their colleagues don't report in via walkie talkie, outposts which can call one another for reinforcements via radios which you can sabotage.

There is so much happening in The Phantom Pain, but it's never overwhelming. Every single interaction, from a single guard investigating a noise, to an entire fortress being sent into alert mode, is depicted with perfect clarity. Radial awareness markers on the interface, each guard's animations, and the radio calls they make between one another, provide enough information to play intentionally on the micro level. And yet, an intoxicating ambiguity underpins these interactions - for without such doubt, there would be little tension.

Camouflage is still important, but the percentage index which communicated how hidden you are on-screen is gone. Even still, as I held my breath and prayed that I was fading away into the terrain, there was never a moment that didn't play out entirely logically. When a guard hears a noise, you don't immediately know whether he'll investigate it himself, or broadcast on his radio that he's about to check it out. If it's the latter, and he doesn't report back, you can expect company.

As tense as these small interactions are, The Phantom Pain is all about scope. It's about climbing a ridge that overlooks a heavily-guarded compound, observing the area with your binoculars, and devising a plan on the macro level. Upon executing that plan, The Phantom Pain almost never tells you "No." The game's scope is not only incredible because of the size of the physical play area it takes place in, but because of the sheer range of complex possibilities the game actively supports. Sure, the more time you spend planning and preparing, the more rewarding the execution feels. Pulling off the perfect stealth infiltration is heart-pounding. But the game is at its best when those micro interactions, both perfectly clear and deliciously ambiguous, act as springboards for surprising or unexpected turns of events.

In one mission, I was tasked with pursuing an armoured convoy being led by a jeep which carried a prisoner. I dropped in at night, and galloped after the tanks on my horse, keeping out of sight by following a ravine by the road they were taking. Suddenly, the convoy came to a stop - the men in the jeep got out to shoo away some wild goats which were blocking the road. I leapt off my horse, crept up to the armoured vehicles, planted explosives and ran to the stationary jeep. As I detonated the bombs, the men turned back to their convoy - just in time to see me gunning the engine, running them both over and driving the prisoner to safety. "Mission complete - maybe you'll break a sweat next time, Boss."

Even when those unexpected events mean you get spotted and half the Soviet army starts bearing down on you, it never feels like you were cheated or the game was being unfair. Some of the most exciting experiences in The Phantom Pain are to be had upon crawling your way back from partial or total failure to a modicum of control over the situation. Once, after being spotted while attempting to sabotage some vehicles in an outpost, I was completely surrounded by tanks and well-armed men. I called in my chopper to provide air support - a risky move, considering the tanks would down it in a single volley.

As the helicopter arrived, blasting The Cure’s Friday I'm In Love from its onboard speakers, I began a one-man campaign of shock and awe to keep the tanks focused on me while the chopper picked them off with its rocket salvos. Smoke grenades, dramatic dives over hills with bullets and explosive shells impacting the ground around me, panicked calls from the chopper as it began to take damage. But it worked, and it fulfilled the objective. The fact that enemies from that point on started carrying rocket launchers to counter my attack chopper runs was just icing on the cake - a small example of how consequences can ripple through the rest of The Phantom Pain's systems.

They're felt throughout the Mother Base metagame, too, which sees you essentially kidnapping enemy soldiers (via balloon) and brainwashing them into joining your military outfit. Once there, they can be assigned to develop new items, provide intel or support in the field, or be sent on their own off-screen combat missions. Though you also collect resources, vehicles and other pieces of kit in the same way, people are your primary resource.

This solves one of the stealth genre's lingering questions: why would you bother pursuing a careful, non-lethal approach, when so many of your items can kill with greater ease? Because dead men don't deliver supply drops to you mid-mission. Though you can manually assign these minions in order to, say, go all-in on a big weapons development project, for the most part they can be left in their automatically-assigned positions and forgotten about. Regardless, the reward for running an efficient base is worth it, for every new item and upgrade expands your range of possible options in the field.

That scope almost never stops expanding. Entirely new game mechanics are introduced 20, even 30 hours in. I completed all story content after 55 hours, and I still don't feel like I'm done with the game. Never before have I played something that so confidently rests on its mechanics to provide the substance and context for purely emergent drama. In doing so, The Phantom Pain is the rarest of creatures: a Japanese immersive sim. Echoes of Thief and Deus Ex and Far Cry 2 meld with the series' own design to create something entirely unique. Unlike its po-faced Western brethren, The Phantom Pain revels in the often comedic and ridiculous results of its emergent interactions.

This is a game where you can defeat a boss by ordering a supply crate to drop on their head. It's bizarre in a way that feels completely, wholeheartedly, intentionally Metal Gear. I don't have nearly enough space to talk about all of these such moments, and I wouldn't want to - they're for you to discover.

Such player-driven drama, comedy, and action eclipses anything in the disappointing scripted narrative. The Phantom Pain is one of the worst Metal Gear stories ever told. It functions neither as a standalone narrative nor as worthwhile insight into the series overall. And yet, The Phantom Pain is the best stealth-action game ever made, one where playing flawlessly is just as thrilling as outright failure. And boy - what a thrill.