Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hen Harriers Nest Failures & Predation On Skye. From Scottish Birds Magazine Feb 14

Uploaded by

rob yorkeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hen Harriers Nest Failures & Predation On Skye. From Scottish Birds Magazine Feb 14

Uploaded by

rob yorkeCopyright:

Available Formats

Scottish Birds 30

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

Hen Harriers on Skye, 200012:

nest failures and predation

R.L. McMillan

Hen Harrier nesting success was studied on Skye from 2000 to 2012, during which period there

were 88 breeding attempts, 47 of which resulted in nest failures, with predation the most likely

cause. To obtain more accurate information on predation at Hen Harrier nests, four cameras were

used at nests between 2009 and 2012. Evidence from these cameras and post-mortem

examinations showed that predation by Red Foxes was the commonest cause of nest failure, 65%

of failures being attributed to foxes. In 75% of cases predation took place after dark. Foxes killed

two incubating adult females on the nest. Foxes mainly predated young from two to four weeks

old, but as recently fledged young return to the nest site to roost, they are also at risk. As fledglings

increased in size, nest sites became more detectable by foxes. In the absence of nest camera

evidence, it was often impossible to attribute a cause of failure, as no conclusive evidence was left

at the nest site. In one instance, foxes visited nest sites over a period of up to 10 days until all

the young were removed. At another site an adult fox brought cubs to a nest when small young

were removed. There was little evidence that adult Hen Harriers can successfully defend their

young against an incursion by a fox either in daylight or darkness.

Plate xx. Caption. Laurie Campbell

31 Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

North

Skye

study area

Sleat

Strathaird

Struan

Portree

Waternish

South

Skye

study area

North

Skye

study area

South

Skye

study area

Figure 1. The Hen Harrier study areas on Skye, 200012.

Introduction

The Hen Harrier Circus cyaneus is a Scottish Biodiversity List Species and meets criterion 3a of

the Species Action Framework as a threatened species which is a focus of conflicts of interest with

stakeholders with other objectives notably game management. It is included in the statutory list

of the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. The Hen Harrier Conservation Framework (Fielding et al. 2011)

considered eight factors potentially affecting their distribution. Constraints ranged from grazing

pressure which might reduce the heathery habitat important for prey species, to wind farms. Illegal

persecution was a significant constraint in some areas, whilst in others, shortage of prey and

suitable nesting habitat were identified. Predation by mammals such as foxes, and avian predators

such as crows, was identified as a possible constraint on breeding success.

Hen Harriers have been studied on Skye, Highland, since 2000 where breeding sites have mainly

been associated with forestry plantations. Although persecution is a significant problem in some

parts of the UK, during the course of this Skye study, there was only one known instance of

human interference. This paper concentrates on nest failure rates and predation by Red Fox Vulpes

vulpes. Unlike other islands in the Hebrides, the fox is well distributed on Skye (Scott 2011).

Scottish Birds 32

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

Study area

When the study commenced in 2000 all the known breeding sites were located in the Sleat and

Strathaird areas of south Skye, but the last of these was successful in 2004. Harriers were also

known to nest in north-central Skye and from 2005 a study area evolved, eventually extending

to 15,000 ha, lying north of the B885 Portree-Struan road and extending to Waternish. As in the

south, the North Skye study area was associated with forestry plantations and moorlands

immediately adjacent. Both study areas are shown in Figure1.

Methods

Fieldwork was conducted under licence issued by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) and followed

current best practice guidelines (Hardey et al. 2009), which recommend a minimum of four visits

to territories to check site occupancy, to locate nests early in incubation, to check for young, and

to check for fledged young.

Green & Etheridge (1999) acknowledged the high risk of predation to this ground nesting species

and emphasised the importance of observing and counting young in flight before determining

fledging success. Hardey et al. (2009), Whitfield & Fielding (2009) and Baines & Richardson (2013)

all provide examples of evidence found at nest sites which could allow causes of failure to be

determined. Attributing causes of failure can be extremely challenging, and not all types of

evidence found can be described as conclusive. A thorough search of nest surrounds was carried

out for evidential traces when a nest failure was discovered. However, with many nest failures

there was no conclusive evidence of causal factors.

In 2008, a successful grant application was made to SNH for nest site cameras in respect of an

action which improves, protects and manages native species and habitats. Four nest site cameras

were purchased from the RSPB Technical Department. Nigel Butcher of the RSPB provided

training and support; for further information on the technology see Bolton et al. (2007). Nest site

cameras were used at selected sites between 2009 and 2012.

Results

200508

Hen Harriers had been monitored on Skye for

nine years from 2000 to 2008. The mean failure

rate of nests was 51% (Table 1). Looking

exclusively at the North Skye data from 2005 to

2008, the failure rate was higher at 62%. The

percentage failure rate peaked at 80% in 2006,

when from the five pairs which laid eggs, 22

young hatched. Two broods failed at less than

two weeks and another two failed at greater

than two weeks, the latter suspected by fox

predation, and only two young fledged. Failure

rates in the next two years remained high and

there was growing concern that predation by

foxes was the main cause of failure (see Fig 2).

However, the evidence was weak, as it was

often impossible to attribute causes.

Plate 2. Evidence of Red Fox predation of Hen Harrier

chick, with bitten and chewed feathers in quill, Skye,

August 2008. R. McMillan

33 Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

Hardey et al. (2009) suggest that predation risk increases as young increase in size. If a predator has

taken large young, evidence may include bitten off feather quills and trails of down feathers. They

also conclude that there may be no signs to indicate small young are taken. In their study in Wales,

Whitfield & Fielding (2009) suggested that partially eaten remains or chewed feathers of the

incubating female and/or nestlings were assumed to be evidence of predation by a mammal (Figure

2). Whitfield & Fielding had also asked observers to record corroborative evidence of the predator

involved such as faeces, hair, feathers or distinctive scent. In the Langholm study, Dumfries &

Galloway (Baines & Richardson 2013), a number of criteria were applied to assign causes of failure.

In the Skye study, the only evidence found by the author was bitten and chewed feathers (Figure 1),

or dead young or adults. In the majority of failures, and despite intensive searches in the vicinity of

nests, there was no evidence of predation, which led to the decision to install digital nest-site cameras.

200912

The data shown in Table 2 from 2009 to 2012 were drawn exclusively from the North Skye study

area. Camera evidence was available for several nests each year, and this was supported by other

evidence such as chewed feathers and post mortem results. Over the four-year study, cameras were

installed at 61% of nests. During the four year period the overall nest failure rate was 57% and

based largely, but not exclusively, on camera evidence, 65% of failures could be attributed to foxes.

A total of eight camera activations resulted from fox intrusions, two when the young were less

than two weeks old, and six when the young were more than two weeks old. After 2009, cameras

were installed only on nests with young as this was considered to be the most vulnerable stage.

However, a female incubating eggs was killed by a fox in 2010, confirming that nests with eggs,

Table 1. Summary of Hen Harrier breeding success, all Skye, 200008.

Year Active Nests Mean Total Total Mean Failed Failed Total Cause

territories clutch young young fledged with with nests of failure

size hatched fledged per nest eggs young failed

2000 4 4 3.7 12 11 2.75 0 1 1 Predator

2001 3 3 3.7 5 5 1.66 1 0 1 Unknown

2002 5 3 2 2 2 0.66 1 1 2 Predator

Unknown

2003 8 7 ? ? 8 1.12 3 1 4 Predator

Unknown

2004 8 8 ? ? 20 2.5 2 0 2 Unknown

2005 10 9 5.4 21 16 1.8 1 2 3 Predator

Unknown

2006 8 5 5.4 22 2 0.40 0 4 4 Weather

Predator

2007 11 9 4.7 42 10 1.1 0 6 6 Predator

2008 11 10 4 28 8 0.8 1 6 7 Predator

Table 2. Summary of Hen Harrier breeding success, North Skye study area, 200912.

Year Active Nests Mean Total Total Mean Failed Failed Total Cause

territories clutch young young fledged with with nests of failure

size hatched fledged per nest eggs young failed

2009 7 6 5.6 16 9 1.5 2 2 4 Fox 2

Unknown 2

2010 12 10 5.4 36 10 1.0 1 6 7 Fox 6

Unknown 1

2011 12 9 5.25 25 15 1.6 0 3* 3 Fox 1

Unknown 2

2012 5 5 5.00 19 8 1.6 1 2 3 Fox 2

Unknown 1

*though RB3 was predated by a fox and two young killed, a single young fledged, so the site is regarded as successful.

Scottish Birds 34

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

as well as brooding adults, can be vulnerable to foxes. In 2011, a nest was deemed to be

successful as a single young fledged despite its two siblings being killed by a fox on camera. Of

the eight recorded predations on camera, only four (50%), had other evidence to indicate that a

fox event had taken place. There was no evidence during the study of nests being visited by any

other mammalian or avian predators. In 2012, a single nest failed late in incubation and though

predation by a corvid could have been a factor, this could not be proved. Hooded Crows Corvus

cornix were frequent nesting neighbours. Figure 3 provides examples of the camera evidence.

Predation of incubating adults

In 2010, an empty nest was located on 16 May with an adult female dead beside it (Plates 4 & 5).

As this female was in moult, it was thought that it had been incubating a clutch of eggs and that

these were subsequently removed by the fox.

Plates 45. Dead female Hen Harrier at the nest, Skye, May 2010. R. McMillan Inset. Same dead female Hen

Harrier as Plate 4 (Skye, May 2010) at the time of the post-mortem, with a fox skull and canines superimposed on

the puncture marks. A.M. Wood

Plate 3. Intrusion of Hen Harrier nest by Red Fox, RBT site, Skye, 23 July 2010. (a) The initial intrusion at 02:24, then

(bc) fox returning at 21:28 to uplift the final dead youngster, which it had concealed. R. McMillan

35 Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

The carcass was examined by A.M. Wood, an avian specialist at the Animal Health and Veterinary

Laboratories Agency, Lasswade, Midlothian. The pattern of injuries found, with fairly symmetrical

distribution of puncture wounds on both sides just behind the wings/axillae, together with the

often paired puncture wounds in the skin and underlying muscles, suggested the bird had been

killed by a fox. In the case of this territory, the male was then successful in attracting another

female, which laid four eggs in a new nest some 200 m further west. Although four young

subsequently hatched, the nest was predated by a fox on camera (see Plate 3).

On 2 June 2011, a nest containing six small young was found and a camera was installed (RB4 in

Table 3). On 10 June, the nest was found to have been predated and the female was dead beside

the nest. All the small young had been removed. Again the carcass was examined by Mr. Wood.

The appearance was consistent with fox predation though maggot activity had enlarged some of

the wounds. The bites on the neck indicated an experienced animal rather than a cub.

In each case, the dead female was left beside the nest. Because the carcasses were discovered and

removed soon after the event, it is possible that a fox would have returned to uplift a carcass as food.

Discussion

Nest sites with cameras were visited more regularly than other sites. There is a view that foxes

may have been attracted to these nests by human scent and trampling of vegetation. The

introduction of larger batteries reduced the frequency of visits from every 5 or 6 days to every

7 or 8 days. As far as is practicable, walk-in approaches to sites were varied. Cameras were used

at 19 nest sites during the study and 52% of these nests were successful. Prior to the camera

study, between 2005 and 2008, of 31 nests which hatched young, only 14 nests were successful

(45%). There was therefore no evidence to suggest that the installation of cameras increased the

failure rate or predation risk.

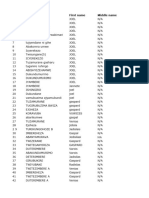

Table 3. Evidence of Hen Harrier breeding success from nest site cameras, Skye, 200912.

Year Nest Date camera installed Result Remarks

code

2009 CH1 29 May on 6 eggs Failed on eggs Female deserted 6 June

(lack of provisioning)

RB1 29 May on 5 eggs Fledged 4 young

RB2 4 June on 3 yg & 2 eggs Fledged 5 young

GR1 4 June on 5 eggs Fox predation 4 June @ 23:15 All 5 young killed

2010 RBL 14 June on 5 young Fox predation 28 June @ 21:31 All 3 remaining young killed

RBU 14 June on 3 yg & 3eggs Fox predation 1 July @ 19:30 All 3 young killed, cubs brought to nest

FB 18 June on 6 young Fox predation (other information) Camera malfunction, but all young killed

CH1 18 June on 4 young Fledged 3 young

GR1 25 June on 4 young Fledged 4 young

RBT 12 July on 3 yg & 1 egg Fox predation 23 July @ 02:20 All 4 young killed

2011 RB4 2 June on 6 young Fox predation 4/5 June Incubating & & 6 young killed (infra-red

failure)

RB1 10 June on 4 young Fledged 4 young

CH1 10 June on 4 young Fledged 3 young

UIG 14 June on 4 young Fledged 3 young

RB3 29 June on 3 young Fox predation 13 July @ 02:00 Killed 2 young, but 1 on wing & fledged

2012 RB3 17.6 on 5 young Fledged 3 young Probably natural brood depletion

RB5 12.6 on 5 young Fox predation 2.7 @23:30 All 4 young killed

CH1 12.6 on 5 young Fledged 5 young

CH2 12.6 on 4 young Fox predation 22.6 @ 01:00 2 young killed & & defended

nest but fox returned 10 days later

& killed remaining 2 young

Scottish Birds 36

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

In Galloway, Watson (1977) provided some evidence of fox predation. He also discussed nest

failures, but attributed this to crows rather than foxes and suggested that successful nesting had

occurred in areas where foxes are plentiful. In later years in Watsons study area, fox predation

became an increasingly important factor and may well have been implicated to some extent in the

extinction of forest-breeding Hen Harriers in Galloway by the mid-1990s (C.J. Rollie pers. comm.).

Simmons (2000) suggests that ground-nesting harrier species are susceptible to ground predators, with

between 9% and 52% of all nests in a sample drawn from seven harrier species, destroyed by predators.

He quotes a figure of 18% in a sample of 480 Hen Harrier nests from Picozzi (1984) in a study in

Orkney, where there are no foxes, although there are ground-nesting crows on the moorlands.

Green & Etheridge (1999) examined Hen Harrier breeding success in relation to grouse moors and

the Red Fox, but their data found no clear evidence for a beneficial effect of the control of foxes

and other predators by moorland gamekeepers, on Hen Harrier nest success. Redpath & Thirgood

(1997) provide some background to the long established study at Langholm. When fox and crow

control ceased on the grouse moor in 2000, it was suggested that higher numbers of generalist

predators impacted on other ground nesting birds including the hen harrier. (Baines et al. 2008).

A later paper (Baines & Richardson 2013) provided a breakdown of nest failure rates and causal

factors in the times when Langholm Moor was keepered and unkeepered, attributing predation

by foxes as the main cause of harrier breeding failure.

In Hen Harrier population studies in Wales, Whitfield & Fielding (2009) found that of 86 failed

breeding attempts where a cause of failure was attributed, 20 nest losses were due to fox.

ODonoghue (2012) found that predation was a significant issue in Ireland, with 19% of nests lost

to predators including foxes. Fielding et al. (2011) referred to previous work (Watson) which

suggested that variation in the aggressiveness with which harriers defend their nests may affect

the susceptibility of eggs and chicks to predation, as may the attentiveness of the parent birds,

which may be influenced by the availability of prey (Amar & Burthe 2001). In the Skye study,

there was no evidence that either of these factors makes any difference. The aggressiveness and

Plate xx. Caption. Laurie Campbell

37 Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

attentiveness of adult females may be a factor during daylight hours, but in the camera study, six

of the eight nest site intrusions by foxes occurred during the hours of darkness. In 2012, a female

harrier aggressively defended her nest to a fox intrusion during darkness but lost two chicks

initially, and the remaining two in the brood, two weeks later. Although not all harriers flee when

a fox intrusion occurs, evidence from this study suggests they offer little resistance to a persistent

fox attack and may well be at risk themselves. Though all the young may not be taken initially,

they will invariably be killed eventually. Of the two intrusions which occurred during daylight

hours, in one instance two live young were left in the nest until the fox returned with cubs two

hours later to remove them. The camera images failed to show any resistance by the adult birds.

In 2005, a webcam at a nest site at Clyde Muirshiel Park recorded the systematic reduction of a

brood of five young Hen Harriers to a single chick, which successfully repelled the fox (C.J. Rollie

pers. comm.). No chick on Skye has been recorded successfully repelling a fox.

The long-established practice of claiming birds have fledged at the point of ringing or when the

young are fully feathered may be unreliable, but remains part of guidance (Hardey et al. 2009).

In 50% of the camera activations in this study, there was no other evidence to suggest that there

had been a fox intrusion at the nest, in other words there had been a clean lift by foxes at the

nest. There is a risk that failures could be attributed to other causes. It might therefore be useful

to include nest failure rates as well as fledging rates, as indicators of the health of Hen Harrier

breeding populations. In areas not managed for Red Grouse, high failure rates at the chick stage

may well indicate a problem of fox predation.

Nest site cameras were deployed as part of the Langholm project between 2008 and 2013 on a

total of 11 nests, two of which failed, but with no evidence of fox intrusions. However, there had

been intensive control of foxes during this period (A. McCluskie pers. comm.). Whilst it might be

argued that foxes will be intensively controlled on all sporting estates, recent analysis of data

from Atholl Estates in Perthshire (McMillan 2011, pers. obs.) shows that predator control on some

grouse moors can be highly variable and directly relates to the efficiency/commitment of

individual gamekeepers. The possibility that Hen Harrier nests will be predated by foxes on some

grouse moors cannot be excluded, and in the context of Langholm, it appears that in 1999, when

grouse moor management was still in place, there was a sudden occurrence of four nest failures

attributed to foxes, in addition to which, two adults were killed on nests (Baines & Richardson

2013). There had been no fox events in the preceding six years of the study. In the subsequent

unkeepered phase of the study 200007 there was an average of a single identified fox event

each year. At Langholm, 19932007, there were a total of 130 breeding attempts from which there

were 41 nest failures and 56% of these occurred when the birds were on eggs. In the Skye study,

200012, there were 88 breeding attempts with a total of 47 failures, 28% of which were on eggs.

The contrast between the two datasets is interesting. The general view amongst raptor workers is

that most fox intrusions occur when broods are at the later stage of development and that is

supported by results from the Skye study. This is not to say that fox predation did not occur at

Langholm, but human disturbance, deliberate or otherwise, may have been a factor given the

disproportionate number of failures on eggs.

Whilst Fielding et al. (2011) acknowledge that foxes can be important predators they were not

included as a predictor in the harrier distribution model. They also concluded that fox impact seems

to be largely on harrier productivity rather than distribution, supported by observations by P.

Haworth in Kintyre, where breeding harriers and foxes appeared to be abundant. However, these

observations are at odds with studies of two areas of Mid-Argyll and north Kintyre, where breeding

birds have disappeared and this has been attributed to a large proportion of failures due to predation,

possibly by foxes (ap Rheinallt et al. 2007). J. Halliday (pers. comm. 2013) has updated these data

showing that four territories in Kintyre occupied in 19972008, were abandoned and this he

attributed to a high incidence of failure due to predation, with foxes the most likely predator. Also

Scottish Birds 38

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

in Argyll at the Moine Mhor NNR, J. Halliday reported that up to three pairs had bred between 1989

and 1996 when the territories were abandoned. Although birds returned in 2010 and 2011, there were

further failures and J. Halliday suspected that high rates of predation, probably by foxes, and lack

of recruitment to the population also explained the demise of this population. In a study in Cowal,

Argyll, from a population of eight pairs in 2003, only a single pair bred successfully in 2013 and

fox predation is considered to be a factor in the population decline (A. French pers. comm.). During

the course of this study, breeding pairs disappeared from south Skye with the exception of 2011,

when a pair returned after a 10-year gap, but failed.

Madders (2010) noted that the extent of first rotation forestry was in decline in the west of

Scotland and predicted that the loss of this habitat would lead to a reduction in numbers of

harriers breeding. New et al. (2011) modelled the population dynamics at Langholm. In afforested

areas, as the canopy closes and small mammals reduce in numbers, New et al. suggest that in the

long term the population size could not be maintained as there would not be enough young

harriers to replace the older birds lost to the population. However, in the context of the Skye study,

whilst there have been some population fluctuations, clutch and initial brood size has remained

high, suggesting that lack of food has not been a factor. The difficulty has been brood survival

and nest failures as a result of fox predation. In the context of the New model, with fewer young

birds fledging, or occasional breeding adults predated by foxes, the problem of recruitment to the

breeding population would be exacerbated. Evidence from Skye, and a number of other areas,

suggests that successive failures as a result of predation may contribute to the abandonment of

territories, making populations less viable, and in some regions directly impacting on distribution.

Digital nest site cameras have proved to be an extremely useful research tool and the images,

along with other material found at nest sites, provides compelling evidence that fox predation of

Hen Harrier nests on Skye is considerably higher than that apparently recorded in any other area

of the UK or Ireland. The technology would seem critical for any future research into establishing

causes of nest failure or brood depletion.

Hayhow et al. (2013) reported that the breeding population of Hen Harriers in the UK and Isle of

Man declined between 2004 and 2010. They concluded that a 20% decrease in Scotland may be

related to habitat change and illegal persecution. It appears that further declines occurred in 2012

which has prompted SNH to commission additional work on the Hen Harrier Conservation

Framework (SNH 2013). In the Skye study, only three nests were found in 2013, the lowest number

recorded since the study commenced.

Problems of human persecution remain a priority for the conservation of this species. However, it

cannot be the exclusive focus when there are clearly other problems in forests and moorlands not

managed for other sporting interests. The challenges facing Hen Harriers are complex, but when

high nest failure rates occur there is a need for a detailed interpretation of causal factors.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Ken Crane and Kate Nellist for detailed observations in the study area. Scottish

Woodlands, Forestry Commission Scotland and J. Robin Dixon provided unrestricted access to the

study area. Access to windfarm roads at Ben Aketil and Edinbane was extremely helpful. The

ongoing monitoring study has been part-funded by Haworth Conservation Ltd. and Ben Aketil

Wind Energy Co. The nest site camera study has been grant-aided by Scottish Natural Heritage,

supported by Atmos Consulting and Haworth Conservation Ltd. Mr A.M. Wood of VLA Lasswade

carried out post mortem examinations of dead adult birds and young. The images are by the

author and Mr. A.M. Wood. I am grateful to other harrier enthusiasts for many useful discussions.

Nigel Butcher of RSPB has provided ongoing help and technical support. Paul Haworth and an

anonymous referee have provided helpful comments on early drafts of this paper.

39 Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds

34:2 (2014)

References

Amar, A. & Burthe, S. 2001. Observations of predation of Hen Harrier nestlings by Hooded Crows

in Orkney. Scottish Birds 22: 6566.

ap Rheinallt, T., Craik, J.C.A., Daw, P., Furness, R.W., Petty, S.J. & Wood, D. (eds.) 2007. Birds

of Argyll. Argyll Bird Club, Lochgilphead.

Baines, D., & Richardson, M. 2013. Hen Harriers on a Scottish grouse moor: multiple factors

predict breeding density and productivity. Journal of Applied Ecology 50: 13971405.

Baines, D., Redpath, S., Richardson, M. & Thirgood, S. 2008. The direct and indirect effects of

predation by Hen Harriers on trends on breeding birds on a Scottish grouse moor. Ibis 150: 2736.

Bolton, M., Butcher, N., Sharpe, F., Stevens, D. & Fisher G. 2007. Remote monitoring of nests

using digital camera technology. Journal of Field Ornithology 78(2): 213220.

Fielding, A., Haworth, P., McLeod, D. & Riley, H. 2011. A Conservation Framework for Hen

Harriers in the United Kingdom. JNCC Report 441. Joint Nature Conservation Committee,

Peterborough.

Green, R.E. & Etheridge, B. 1999. Breeding success of the hen harrier in relation to the

distribution of grouse moors and the red fox. Journal of Applied Ecology 36: 472483.

Hayhow, D.B., Eaton, M.A., Bladwell, S., Etheridge, B., Ewing, S.R., Ruddock, M., Saunders, R.,

Sharpe, C., Sim, I.M.W. & Stevenson, A. 2013. The status of the Hen Harrier, Cygnus cyaneus,

in the UK and Isle of Man in 2010. Bird Study 60: 446458.

Hardey, J., Crick, H.Q.P., Wernham, C.V., Riley, H.T., Etheridge, B. & Thompson, D.B.A. 2009.

Raptors: a field guide to surveys and monitoring. 2nd edition. The Stationery Office, Edinburgh.

Madders, M. 2000. Habitat selection and foraging success of Hen Harriers Circus cyaneus in west

Scotland. Bird Study 47: 3240.

McMillan, R.L. 2011. Raptor persecution on a large Perthshire estate: a historical study. Scottish

Birds 31(3): 195205.

New, L.F., Buckland, S.T., Redpath, S. & Matthiopoulus, J. 2011. Hen harrier management: insights

from demographic models fitted to population data. Journal of Applied Ecology 48: 11871194.

ODonoghue, B.G. 2012. Duhallow Hen Harriers Circus cyaneus - from stronghold to just holding

on. Irish Birds 9: 349356.

Picozzi, N. 1984. Breeding biology of polygynous Hen Harriers in Orkney. Ornis Scandinavica 15: 110.

Redpath, S.M. & Thirgood, S.J. 1997. Birds of Prey and Red Grouse. London, Stationery Office.

Scott, R. (ed). 2011. Atlas of Highland Land Mammals. Highland Biological Recording Group.

Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) 2013. www.snh.gov.uk/protecting-scotlands-nature/species-

action-framework/species-action-list/hen-harrier/

Simmons, R.E., 2000. Harriers of the World: their behaviour and ecology. Oxford University Press.

Watson, D. 1977. The Hen Harrier. T. & A.D. Poyser.

Whitfield, D.P. & Fielding, A.H. 2009. Hen Harrier population studies in Wales. CCW Contract

Science No. 879. www.alanfielding.co.uk/fielding/pdfs/CCW%20contract%20science%

20report%20879.pdf

R.L. McMillan, Askival, 11 Elgol, Broadford, Isle of Skye IV49 9BL.

Email: bob@skye-birds.com

Revised ms accepted February 2014

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Trio of Times Letters in Response To The Godfather of MushroomsDocument2 pagesTrio of Times Letters in Response To The Godfather of Mushroomsrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- 'Lemmy's Namsen' - Rough CutDocument4 pages'Lemmy's Namsen' - Rough Cutrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Charles Clover On Chris Packham in The Sunday Times 13.9.15Document2 pagesCharles Clover On Chris Packham in The Sunday Times 13.9.15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Hen Harrier Action Plan. Philip Merricks in Country LifeDocument1 pageHen Harrier Action Plan. Philip Merricks in Country Liferob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Conflicts in Conservation. The Field Magazine Apr 16Document3 pagesConflicts in Conservation. The Field Magazine Apr 16rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- 'Save Tuna Eat Squirrel'. Ben Macintyre in The Times Oct 15Document2 pages'Save Tuna Eat Squirrel'. Ben Macintyre in The Times Oct 15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- 20 Years of Farmland Bird Research in Bird Study Via GWCT and RSPBDocument22 pages20 Years of Farmland Bird Research in Bird Study Via GWCT and RSPBrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Dear Sir...Document1 pageDear Sir...rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Langholm Moor - Interests in Raptor Grouse ChallengesDocument2 pagesLangholm Moor - Interests in Raptor Grouse Challengesrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Waste Food. The Times Leading Article 12.8.15Document1 pageWaste Food. The Times Leading Article 12.8.15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- 'Sweets' Fishing Tackle Shop. The Oldie, August '15Document2 pages'Sweets' Fishing Tackle Shop. The Oldie, August '15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Plant More Trees. 100th Letter in The TimesDocument1 pagePlant More Trees. 100th Letter in The Timesrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Dung Beetles. Farmers Weekly Aug 15Document3 pagesThe Importance of Dung Beetles. Farmers Weekly Aug 15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Humans As Apex Predators - A Need To Embed Our Influence in Trophic CascadesDocument8 pagesHumans As Apex Predators - A Need To Embed Our Influence in Trophic Cascadesrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Fisheries and Farming. CLA Magazine June 15Document1 pageFisheries and Farming. CLA Magazine June 15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Vegetation Burning For Game Management in The UK Uplands. Biological Conservation 2015Document8 pagesVegetation Burning For Game Management in The UK Uplands. Biological Conservation 2015rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- The Times. Nature Notebook Aug 15Document1 pageThe Times. Nature Notebook Aug 15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Challenge of Natural Capital. Letter in RICS Modus 6/15Document1 pageChallenge of Natural Capital. Letter in RICS Modus 6/15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Hay Festival 21 May 15: Affordable Food and Pay More For Wildlife?Document1 pageHay Festival 21 May 15: Affordable Food and Pay More For Wildlife?rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- 'New Demands Old Countryside' by Rob Yorke FRICSDocument78 pages'New Demands Old Countryside' by Rob Yorke FRICSrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Prawn Hunting. 100th Countryfile MagazineDocument3 pagesPrawn Hunting. 100th Countryfile Magazinerob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Hay Festival Food and Farming - B&R Express May 2015Document1 pageHay Festival Food and Farming - B&R Express May 2015rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Bristol Food Connections Festival May 2015 - RY's TalkDocument3 pagesBristol Food Connections Festival May 2015 - RY's Talkrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- 'What's Good For Shooters Is Good For The RSPB' Clive Aslet in The TimesDocument2 pages'What's Good For Shooters Is Good For The RSPB' Clive Aslet in The Timesrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Tension Between Pollinators and Pesticides. RICS Land Journal Spring 2015Document1 pageTension Between Pollinators and Pesticides. RICS Land Journal Spring 2015rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Owen Paterson in The Field Magazine May 15Document4 pagesOwen Paterson in The Field Magazine May 15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Wildlife Management and Habitat Loss. Times Letter 21.5.15Document1 pageWildlife Management and Habitat Loss. Times Letter 21.5.15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Review of 'What Nature Does For Britain' by Tony Juniper in Countryfile MagDocument1 pageReview of 'What Nature Does For Britain' by Tony Juniper in Countryfile Magrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Tilting at Wildlife: Reconsidering Human-Wildlife ConflictDocument4 pagesTilting at Wildlife: Reconsidering Human-Wildlife Conflictrob yorkeNo ratings yet

- Indoor Cows. Times Letter Jan 15Document1 pageIndoor Cows. Times Letter Jan 15rob yorkeNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Awareness on Waste Management of StudentsDocument48 pagesAwareness on Waste Management of StudentsJosenia Constantino87% (23)

- Contract Day Watchman SHS - O. SanoDocument2 pagesContract Day Watchman SHS - O. SanoZaldy Tabugoca100% (2)

- Indus Script - WikipediaDocument55 pagesIndus Script - WikipediaMuhammad Afzal BrohiNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Honda automotive companyDocument2 pagesIntroduction to Honda automotive companyfarhan javaidNo ratings yet

- A Simple Gesture RomanDocument2 pagesA Simple Gesture Romanapi-588299405No ratings yet

- Controller Spec SheetDocument4 pagesController Spec SheetLuis JesusNo ratings yet

- Department of Labor: Logsafe Fall 01Document8 pagesDepartment of Labor: Logsafe Fall 01USA_DepartmentOfLaborNo ratings yet

- Gauda Kingdom - WikipediaDocument4 pagesGauda Kingdom - Wikipediaolivernora777No ratings yet

- Manticore Search Case-Study Layout-InternationalDocument1 pageManticore Search Case-Study Layout-Internationalnilasoft2009No ratings yet

- Common Customer Gateway Product SheetDocument2 pagesCommon Customer Gateway Product SheetNYSE TechnologiesNo ratings yet

- Review Jurnal Halo EffectDocument12 pagesReview Jurnal Halo Effectadinda veradinaNo ratings yet

- Distributes Weight EvenlyDocument5 pagesDistributes Weight Evenlykellie borjaNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Poem by Nissim Ezekiel Summary and AnalysisDocument7 pagesEnterprise Poem by Nissim Ezekiel Summary and AnalysisSk BMNo ratings yet

- Oblicon Chap 1 5Document15 pagesOblicon Chap 1 5Efrean BianesNo ratings yet

- Encoder DecoderDocument6 pagesEncoder Decodermarkcelis1No ratings yet

- Here The Whole Time ExcerptDocument18 pagesHere The Whole Time ExcerptI Read YA100% (1)

- JVC Mini DV and S-VHS Deck Instruction Sheet: I. Capturing FootageDocument3 pagesJVC Mini DV and S-VHS Deck Instruction Sheet: I. Capturing Footagecabonedu0340No ratings yet

- M-Commerce Seminar ReportDocument13 pagesM-Commerce Seminar ReportMahar KumarNo ratings yet

- Earth First's - Death ManualDocument9 pagesEarth First's - Death Manualfurious man100% (1)

- D20 Modern - Evil Dead PDFDocument39 pagesD20 Modern - Evil Dead PDFLester Cooper100% (1)

- Freebie The Great Composerslapbookseries ChopinDocument24 pagesFreebie The Great Composerslapbookseries ChopinAnonymous EzNMLt0K4C100% (1)

- Cutaneous Abscess Furuncles and CarbuclesDocument25 pagesCutaneous Abscess Furuncles and Carbuclesazmmatgowher_1219266No ratings yet

- Data Compilation TemplateDocument257 pagesData Compilation TemplateemelyseuwaseNo ratings yet

- Parallel Worlds ChessDocument2 pagesParallel Worlds ChessRobert BonisoloNo ratings yet

- The Role of Standards in Smart CitiesDocument19 pagesThe Role of Standards in Smart CitiesmeyyaNo ratings yet

- Korean Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesKorean Lesson Planapi-272316247No ratings yet

- Occlusal Considerations in Implant Therapy Clinical Guidelines With Biomechanical Rationale PDFDocument10 pagesOcclusal Considerations in Implant Therapy Clinical Guidelines With Biomechanical Rationale PDFSoares MirandaNo ratings yet

- Sinha-Dhanalakshmi2019 Article EvolutionOfRecommenderSystemOv PDFDocument20 pagesSinha-Dhanalakshmi2019 Article EvolutionOfRecommenderSystemOv PDFRui MatosNo ratings yet

- B2 First Unit 11 Test: VocabularyDocument3 pagesB2 First Unit 11 Test: VocabularyNatalia KhaletskaNo ratings yet

- Jack Welch and Jeffery Immelt: Continuity and Change at GEDocument40 pagesJack Welch and Jeffery Immelt: Continuity and Change at GEPrashant VermaNo ratings yet