'I Never Told Anyone Not to Vaccinate'

Vaccination is among the few definitive tenets of disease prevention, but because of rampant misinformation, fear, and scientific illiteracy, rare infections have come back to life.

In the way the word cancer quiets a room, polio once did. Now it sounds archaic. So does measles, which can make it difficult to comprehend that a woman from Seattle came down with measles two weeks ago after a Kings of Leon concert. That song "Sex on Fire" that you sometimes still hear on the radio? They were playing that while a woman was developing measles. Which will not impress you if you spent 2011 in France, where there were 15,000 cases of measles. Then, in the U.S. in 2012, almost 50,000 people got whooping cough.

Because parents are choosing to forgo or delay vaccinations, one in eight American kids has not received all that are medically recommended. In trying to understand the drivers of that idea, which is at odds with the science of infectious disease and public health policy, Jenny McCarthy has emerged the most visible detractor. The name of the host of The View now appears in medical journals. This week though, in an unexpected move, McCarthy said she is not against vaccinating children to protect them from infectious diseases. “I am not ‘anti-vaccine,’” she wrote in a column in Chicago Sun-Times Splash section on Sunday. That might seem like a dramatic change of heart, except that she says it’s not. “I’ve never told anyone to not vaccinate.”

That’s a false sentence, but we don’t need to pick that apart. Well, okay, here's just one of her anti-vaccine statements from 2009: “It’s going to take some diseases coming back to realize that we need to change and develop vaccines that are safe. If the vaccine companies are not listening to us, it’s their fucking fault that the diseases are coming back. They’re making a product that’s shit. If you give us a safe vaccine, we’ll use it. It shouldn’t be polio versus autism.”

Really, though; an argument with Jenny McCarthy over consistency has no winners. Vaccines are safe, and widespread vaccination programs are definitely good for public health. Writers at Slate, Time, and other places already exhaustively rebuked McCarthy for backpedaling and hypocrisy in this column. It's a lot of fun to catch someone contradicting herself, but the old statements are in the past. Jenny McCarthy really isn't the enemy; the misinformation she spread is. As long as she ends up on the side of the discussion that leads to the fewest outbreaks of mumps—the discussion which most doctors agree shouldn’t even be happening, and diseases that definitely shouldn’t—fine.

Except they are, and it is. And McCarthy didn’t stop writing there. She turned the argument into one of free speech and rights to raise children as one chooses. She said everyone should be free to dissent. McCarthy quoted a blogger and life-coach named Nancy Colasurdo, whose words, McCarthy said, “echo and articulate my concern with inflexible thinking”:

Here’s how it goes in this country, like everything else—black or white. Those are your choices. You either fall in line with 40-plus vaccines your doctor recommends on his or her schedule or you’re a wack-job “anti-vaxxer.” Heaven forbid you think the gray zone is an intelligent place to reside and you express doubt or fear or maybe want to spread the vaccines out a bit on this tiny person you’ve brought into the world.

We vaccinate kids against 16 diseases. Most vaccinations require three or four doses. The one-poke-per-visit approach is not beneficial and, worse, leaves kids unnecessarily vulnerable during the time between visits. Eminent pediatricians Paul Offit and Kristen Feemster at the University of Pennsylvania wrote last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Pediatrics, “Delaying vaccines offers no clear benefit and puts children at unnecessary risk. The most significant consequence is increasing the amount of time an infant or young child is susceptible to a vaccine-preventable disease, often during the time when a child is most at risk for severe infection.”

Among the untoward effects Offit and Feemster also note but deem less significant: “Delaying administration of measles-containing vaccines increases the risk of fever and seizures.”

McCarthy also wrote, similarly, “I believe parents have the right to choose one poke per visit.”

It’s odd to turn it into an issue of rights in that way. At best that’s like giving a first-amendment defense for referring to Ukraine as “the Ukraine.” Except worse, because you are messing with another person’s life. Parents have a right to let their kids sit on the couch watching Ridiculousness and eating yogurt from tubes all day. In a lot of ways, parents have a right to be bad parents. Last year a German boy named Micah died because of a measles infection. Too young to be vaccinated himself, he contracted measles from a willfully unvaccinated child in their pediatrician’s waiting room. One family’s free choice not to vaccinate resulted in the death of another’s boy.

And then, in some further misappropriation of concerns, McCarthy wraps up the column in a very strange, straw-man way: “Should a child with the flu receive six vaccines in one doctor visit? Should a child with a compromised immune system be treated the same way as a robust, healthy child? Shouldn’t a child with a family history of vaccine reactions have a different plan? Or at least the right to ask questions?”

Closing with these provocations deflects attention from her real argument, but the answers are no, no, possibly, and yes. Addressing these variables, all, is standard practice. Any medical professional is expected to take them into account. It’s counterproductive and polarizing to imply otherwise. When we say vaccines are safe, it doesn’t mean physicians give them at will, without regard to a patient's unique medical conditions. Vaccines are safe, but we don’t give them to kids while they are more than mildly ill with another infection. Bowling is safe, but if your arm is freshly broken it's not the best idea to bowl with it.

Whenever I write on stories like this, people ask me why I give it the time of day. I wrote about a neurologist who says that eating carbohydrates is the cause of most mental illness, because his book was number one on The New York Times bestseller list. As long as Jenny McCarthy has a popular talk show and a newspaper column that can get shared on Facebook seven thousand times like this column did, it’s worth taking seriously. Assume McCarthy isn’t purposefully deflecting to distract from the backpedaling; that she genuinely feels she can’t ask questions about vaccines. And other people feel that way, too. So some of them opt against vaccinating their kids. In that case being dismissive is a failure of health providers and medical journalists. Colasurdo’s prose in referring to “this tiny person you’ve brought into the world” is syrupy but gets to something real. The responsibility of parenthood can be overwhelming. It can stir suspicion and concern that supplant reason among reasonable people.

Exasperating as it can be for experts and journalists who hear about vaccine conspiracy theories and discredited research regularly, for years, concerns are still best addressed seriously. Dismissing concerned parents out of hand is dangerous to the culture on the whole. Go after the misinformation, not the misinformed. McCarthy is not an aberration, in that celebrities without medical expertise have and will continue to shape public health. Often for better, often not; either way it's powerful and the effects are pervasive.

In preventive medicine, there is so, so much we don’t know definitively. What’s the best diet? Minimize added sugar and trans fat, go high on fiber, plants, and omega-3 fatty acids, and that’s nearly all I can say. Should I be taking vitamin D supplements? Wasn't there just a study that said it will make me less likely to die? Well, you'll die, but maybe you should try taking them, in that getting more vitamin D might make you less likely to die of cancer or heart disease, but it’s not generally recommended; and it might accumulate in your organs and cause irreversible kidney damage. How many eggs should I eat? Ah probably not too many, but they’re not as bad as we once thought. How much wine? People say one to two glasses a day, but that is literally a 100 percent difference between one and two glasses. Just tell me the right answer.

Preventive medicine is a world of gray areas, the sort McCarthy advocates in her column. There are not that many absolutes: Sleep seven (eight?) hours a night, get your heart rate up as often as possible, have working carbon monoxide detectors, don’t eat lead paint, and get vaccinated. Among a few other things. The findings of medical science are only relevant to the extent that they can be incorporated into culture. Despite the black-and-white nature of finite scientific questions, knowledge in aggregate, in the context of life, puts answers on continua, spectra, and in gray areas. That's where most medical decisions happen.

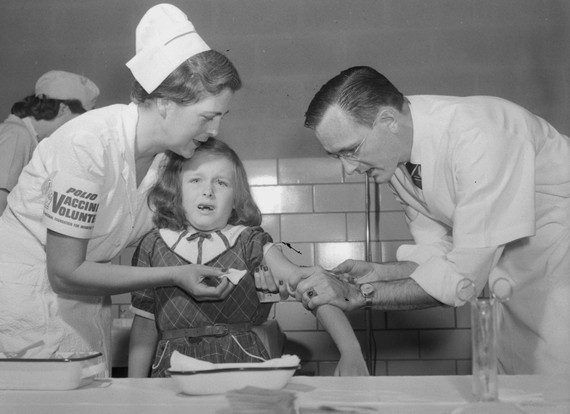

Dissent and constant testing of norms are central to science. It was heterodox thinking across gray areas that led Jonas Salk to the polio vaccine in the first place. Skepticism is a virtue, especially of things simplistic. So is embracing the grayness of uncertainty in health and disease. But this is one place where there's clean contrast, not gray.