Among other things, Albert Camus would remind his fellow Frenchmen of the poisonous legacy of the Algerian war that did great damage to society in both Algeria and metropolitan France, as the French empire unraveled in the 1950s. He is in fact reminding us of the bitter history that he -- an Algerian-born Frenchman -- lived through, via the 2013 English translation of his fascinating, long-forgotten book Algerian Chronicles.

Among other things, Albert Camus would remind his fellow Frenchmen of the poisonous legacy of the Algerian war that did great damage to society in both Algeria and metropolitan France, as the French empire unraveled in the 1950s. He is in fact reminding us of the bitter history that he -- an Algerian-born Frenchman -- lived through, via the 2013 English translation of his fascinating, long-forgotten book Algerian Chronicles.

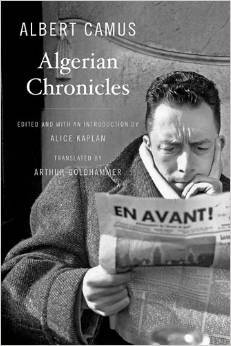

His decision to compile the book -- a collection of his journalism from rural Algeria dating back to the 1930s and his urgent occasional writing as the situation deteriorated through the 1940s and 1950s -- was an act of integrity and of faith, unrequited at the time, as its publication sank like a proverbial stone because radicalized factions on all sides were refusing to hear voices of moderation. But the translation by Arthur Goldhammer and publication by Harvard University Press amplify the great moralist's enduring relevance by displaying the power, or at least the human value, of moral and intellectual clarity and honesty, even when these qualities are demonstrably ineffectual in political terms.

What Camus saw clearly above all was the moral vacuousness of us-versus-them factional rhetoric. "The truth, unfortunately, is that one segment of French public opinion vaguely believes that the Arabs have somehow acquired the right to kill and mutilate, while another segment is prepared to justify every excess," he wrote. "Each side thus justifies its own actions by pointing to the crimes of its adversaries."

The proximate occasion for my publishing this short appreciation is, of course, the terrorist murder of a dozen staff of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris on January 7. But Camus speaks to us far beyond France, and beyond any particular event. To those Americans who are still confused about or oblivious to the implications of the recent Senate torture report, he has this to say:

The reprisals against the civilian population of Algeria and the use of torture against the rebels are crimes for which we all bear a share of responsibility. That we have been able to do such things is a humiliating reality that we must henceforth face. Meanwhile, we must refuse to justify these methods on any grounds whatsoever, including effectiveness. Once one begins to justify them, even indirectly, no rules or values remain. One cause is as good as another, and pointless warfare, unrestrained by the rule of law, consecrates the triumph of nihilism.

The tragedy and poignancy of Camus's writings on Algeria is that few on any side listened to him at the time. But therein also lies his relevance to us right now, half a century later. He refused to "grandstand for the sake of an audience," as he put it: "I have decided to stop participating in the endless polemics whose only effect has been to make the contending factions in Algeria even more intransigent and to deepen the divisions in a France already poisoned by hatred and factionalism." In today's world, a writer like the Pakistani novelist Bina Shah is in a similar position. We can hear echoes of his attitude in her January 7 series of tweets :

I refuse to condemn/apologise as a Muslim. The people that did this stand for the polar opposite of what I believe in. ... Those of you asking us "peaceful Muslims" to condemn terrorists rather naively assume they're actually going to listen to us. ... I do not apologise for Islamist terrorists because I live my life in opposition to everything they stand for. That is braver.

Camus's credibility, then and now, lies largely in his willingness to deploy his moral authority, as both a prominent French liberal and a longtime public sympathizer with the Algerian cause, to condemn terrorism explicitly and forcefully:

The massacres of civilians must first be condemned by the Arab movement, just as we French liberals condemn the massacres of the repression. Otherwise, the relative notions of innocence and guilt that guide our action would disappear in the confusion of generalized criminality, which obeys the logic of total war. ... When the oppressed take up arms in the name of justice, they take a step toward injustice.

Most poignant, and most relevant, to us and our times, and what comes through most clearly in Camus's Algerian writings, is the writer's humanity. In her 1985 essay "The Essential Gesture," reflecting on the variety a ways to involve oneself, as a writer, in events and the times and activism, Nadine Gordimer reminds us that it was Camus who famously said, "It is from the moment when I shall no longer be more than a writer that I shall cease to write."

Much of the enduring human appeal of Camus lies in his unwillingness to distance himself as an intellectual from his own visceral and particular loyalties -- and why should he? Why should any of us? The correct version of the response he gave to an Algerian student at a press conference in Stockholm in 1957, much misquoted and misunderstood at the time, illustrates how his moral and political positions arose directly out of his personal agony as a pied noir or Frenchman born in Algeria: "People are now planting bombs in the tramways of Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, then I prefer my mother."

--

Ethan Casey is the author of Alive and Well in Pakistan: A Human Journey in a Dangerous Time (2004), called "intelligent and compelling" by Mohsin Hamid and "wonderful" by Edwidge Danticat, and Home Free: An American Road Trip (2013), about which Paul Rogat Loeb said: "Ethan Casey listened hard and well in his books on Haiti and Pakistan. Now he's listening to America." He is also the author of Bearing the Bruise: A Life Graced by Haiti (2012). Web: www.ethancasey.com. Facebook: www.facebook.com/ethancasey.author.