Is NASA's Plan to Lasso an Asteroid Really Legal?

NASA's ambitious asteroid-capture mission is seemingly being blueprinted with little dialogue about whether or not it is actually legal.

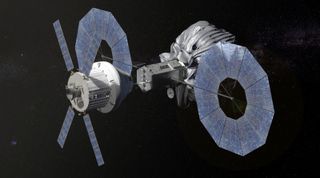

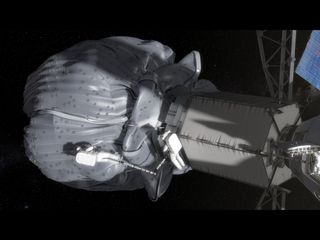

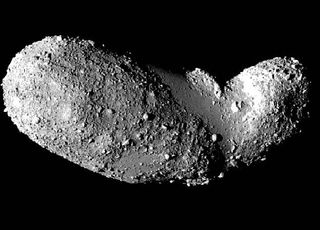

NASA intends to grab an asteroid and drag it to a stable orbit near the moon, where it can be visited by astronauts, perhaps as early as 2021. But does this bold plan run afoul of 1967's Outer Space Treaty (OST), which provides the basic framework of international space law, or 1972's Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects?

SPACE.com asked several lawyers with space specialties to offer views about the legality of tagging, bagging and shoving an asteroid around. [NASA's Asteroid-Capture Mission in Pictures]

Certain to be lawful

"Retrieving an asteroid and placing it in a stable orbit in the Earth-moon system for additional exploration is nearly certain to be lawful under the Outer Space Treaty at this stage of space exploration," said law professor Matthew Schaefer, director of the Space, Cyber and Telecommunications Law Program at the University of Nebraska College of Law in Lincoln.

As enshrined in the Outer Space Treaty, Schaefer said, countries have freedom of exploration and use of celestial bodies. Critics of such a conclusion, he said, may point to language in Article I of the OST requiring "free access to all areas of celestial bodies" and the nonsovereignty language in Article II.

"However, as a practical matter, any claims based on free access or nonsovereignty obligations will not even arise unless two nations are both targeting the same asteroid or same area of a celestial body for exploration," Schaefer said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Given the large number of asteroids and the limited number of nations with the requisite capabilities to execute such a challenging mission, Schaefer said that it is unlikely at this stage of space exploration that two nations would target the same asteroid at the same time. [Animation of NASA's Proposed Asteroid-Retrieval Mission (Video)]

Free access

Schaefer added that if one nation is seeking to move or mine the very same asteroid another country is already moving or mining, then the latecomer must show "due regard" for the interests of the party conducting the initial asteroid retrieval and mining mission.

In fact, if the second nation's activities "would cause potentially harmful interference" with the first nation's activities, the second nation is required to consult in advance with the other country, Schaefer said.

Furthermore, if an asteroid is so small that it allows only one mining or exploration operation, Schaefer said it would be hard to argue that a nation that does so first is somehow infringing on others' "free access" because "such an interpretation would strip away the guaranteed freedom of the first nation to explore and use." [How Asteroid Mining Could Work (Infographic)]

In sum, Schaefer said that there are "no definitive, significant legal barriers" to an asteroid-capture mission at this stage of space exploration.

Oops factor

But what happens if an asteroid-retrieval effort goes wrong and ends up threatening the Earth?

"If such retrieval accidentally put the asteroid in an uncontrolled orbit and it caused damage to space objects in orbit, itself a highly unlikely event, the question can be raised whether the party moving the asteroid is now liable for damages caused to the space objects by the asteroid," Schaefer said.

Schaefer said that the Liability Convention establishes a "fault-based standard" for damage in space, and that a variety of factors would likely affect liability, including any advance warnings given.

"Additionally, the space treaties liability provisions refer to 'space objects' and 'launching of a space object' and an asteroid that has been moved does not fit comfortably within those terms," Schaefer said. Thus, the specific liability rules of the space treaty might not apply at all, he added, so general international law may come into play.

Playing catch-up

"Space law is a relatively new area of law. It is still playing catch-up with the new space activities on the horizon," said Michael Listner, the founder and principal of the firm Space Law and Policy Solutions, based in New Hampshire. "NASA's proposed retrieval mission is no exception."

Listner told SPACE.com that while there are no specific laws that address moving an asteroid, the current body of space law would have some relevance. For example, the United States is a signatory to the Outer Space Treaty, and some of the provisions may thus apply, he said.

Article VI of the OST stipulates that as a signatory, the United States bears international responsibility for its national activities in outer space, including operations on or around the moon and other celestial bodies, Listner said, "whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by nongovernmental entities."

NASA is an agency of the United States, and moving an asteroid would be considered a space activity, Listner said, so the United States would bear international responsibility to ensure that NASA's activities conform to the OST.

National appropriation?

"There might also be a question of whether snagging an asteroid and relocating it could be considered national appropriation in violation of Article II of the Outer Space Treaty," Listner said. "If a target asteroid has some tangible value in terms of mineral resources, some of the signatories to the OST could raise concern that capturing and relocating an asteroid equates to national appropriation."

"However, on the flip side, if NASA were to capture a small asteroid and relocate it without raising international objections, it could create a foundation for an international customary norm in terms of space property rights," he added.

As far as the "oops" factor goes, Listner said that the maxim of expecting the unexpected should be heeded. The possibility exists that attempting to place an asteroid into an orbit close to Earth or around the moon could lead to some unforeseen consequences, he said. For example, the space rock could be jostled out of orbit and interfere with satellites in the geosynchronous belt, or, even worse, head toward Earth and cause damage on the planet's surface.

Normally, in either situation, the Liability Convention would apply, but this activity is outside the norm and the question is whether an errant asteroid could be considered a "space object" under the definition Article 1(d) of that Convention, Listner said. Also, it is questionable whether the United States could be viewed as the "launching state" under Article 1(c), he said, considering that the asteroid technically was not launched from the United States.

It should also be pointed out, however, that NASA is currently planning to grab a roughly 25-foot-wide (7.6 meters) asteroid that weighs about 500 tons. Such a small space rock would almost certainly burn up completely in Earth's atmosphere if it somehow ended up coming toward Earth.

Rule of thumb

One other pertinent consideration, Listner said, is whether the United States should invoke Article IX of the OST to brief other spacefaring nations on the proposed activity, since it could potentially contaminate the outer space environment.

"Article IX has only been invoked once and that was after the fact by Japan when China performed its notorious anti-satellite test in 2007," Listner said. Article IX has never been invoked pre-emptively by any signatory to the Outer Space Treaty, he added.

"The general rule of thumb when it comes to this proposed mission is to assume the worst from a legal perspective and be prepared to deal with it if the worst actually comes to pass," Listner said.

Simple and complex

George Robinson, a space law practitioner and retired Associate General Counsel for the Smithsonian Institution, said the law regarding NASA's current agenda to undertake an asteroid retrieval initiative is both simple and complex.

Most practicing and academically oriented space lawyers, Robinson told SPACE.com, believe the related issues are complicated and that potentially applicable laws are anything but clear, "if at all existent beyond the provisions in the seriously outdated 'mother treaty for space,' the 1967 Outer Space Treaty."

A more realistic assessment of potentially applicable space-related laws is that treaties, conventions and relevant public and private international laws tend to emphasize everything being for the benefit of all nations and all humankind, Robinson said.

"The moribund nature of the [1972] Seabed Treaty reflects the unlikelihood of private, and even governmental, investment in necessary research and extrapolation/conversion to useful/profitable products that must be shared by noninvesting, nonparticipating nations," Robinson said.

Agreements are intended — indeed, designed — to be broken or ignored in whole or in part at some point, either by signatories or nonsignatories, Robinson suggested.

"Paper tiger with no teeth"

Reference to the 1967 OST "offers no real help in answering questions of law related to asteroid retrieval and/or mining," Robinson added. "In this context, a variety of academicians and practitioners of space law have an equal variety of opinions regarding asteroid mining and ownership of exploited space resources, whether by governments or the private sector."

Robinson believes that the OST, now more than 45 years old, is in dire need of "extensive re-evaluation and amending, or trashing altogether and starting over again" to meet current and projected realities of space research, migration, habitation and resource exploitation capabilities.

"The OST at present is a paper tiger with no teeth and little interest in dental implants that would allow substantive answers to pressing legal questions and answers, such as those presented by plans for asteroid mining and potential retrieval for a near-Earth trajectory," Robinson said.

For readers interested in more information regarding space law, go to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs:

http://www.unoosa.org/pdf/publications/st_space_61E.pdf

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin's new book "Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration" published by National Geographic. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He was received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.