/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/33021677/1--ostracod-sperm-140513-670x440.0.jpg)

Australian researchers have found a 16 million-year-old fossilized female ostracod — a millimeter-long, clear crustacean, related to shrimp — filled with sperm.

The specimen, embedded in limestone, was excavated from an archaeological site in northwest Australia way back in 1988, but only identified recently. Now described in a paper published in the the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, it contains the oldest rock-preserved sperm that's ever been found.

The ostracod was found along with four males, all filled with the species' characteristic giant sperm cells — longer than the creatures' bodies, but tightly coiled up inside. These delicate features, which seldom survive the fossilization process, were preserved by layers of bat guano.

Inside the rare discovery

Renate Matzke-Karasz

The fossil, shown above, was found by a group of University of New South Wales archaeologists at the Riversleigh archaeological site decades ago, and recently sent to a team of ostracod specialists led by Renate Matzke-Karasz.

Although the creature's outer shell was mostly preserved, a piece of it had been cracked off — fortuitously exposing the sperm and other soft tissues preserved inside. Using X-rays and microscopes, the specialists were able to peer inside the fossil and identify sperm cells — complete with intact nuclei — and other internal structures.

The fact that the female contained sperm cells indicates she was killed shortly after copulating. They aren't the oldest fossilized sperm cells ever found — that title goes to 40 million-year-old sperm preserved in amber that once belonged to an insect called a springtail — but they are the oldest petrified sperm (that is, preserved in rock).

That makes two sperm records that ostracods are runners up for: after a species of fruit fly, ostracods have the second-longest sperm, relative to their body size, in the animal kingdom.

Why scientists are so excited about these giant sperm

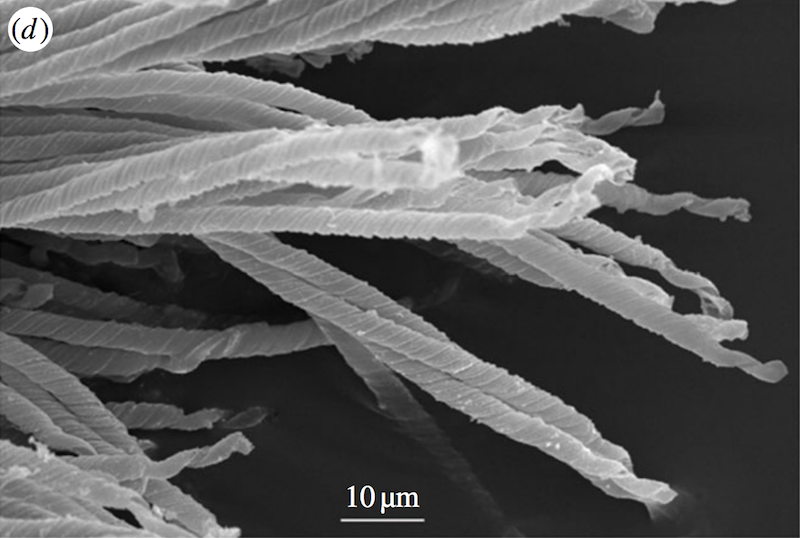

A microscopic close-up of the sperm. Renate Matzke-Karasz

Apart from the novelty of finding such ancient sperm, the discovery actually provides real scientific value.

For one, the discovery helps scientists better understand ostracods and how they evolved such unusual gametes over time. Until now, the only parts of ancient ostracods that had been found were generally their shells, rather than any remnants of their living tissue inside.

But in this case, along with the sperm cells, the fossils include Zenker organs, muscular pumps still used by male ostracods today to inject the giant sperm cells into females. This shows that a similar mechanism was in place at least 16 million years ago.

There's also the remarkable fact that the sperm cells could be preserved completely intact in three dimensions, rather than flattened, as many fossils are. The researchers say that the high levels of phosphorus in the bat feces that rained down and hardened atop the fossils likely helped mineralize the soft tissues.

Previously, the archaeological site — which was once a cave at the center of a biodiverse rainforest — has yielded fossilized insects with their internal muscles intact, perfectly preserved leaf cells, and fossilized marsupials with soft tissue still present in their eye sockets. This new discovery, along with the others, suggests that Riversleigh contains many more interesting fossils waiting to be found.