Despite rapid economic growth, gender disparities have remained deep and persistent in India and other South Asian countries. The UN Gender Inequality Index has ranked India below several Sub-Saharan African countries. Gender disparities are even more pronounced in economic participation and women’s business conditions in India. Using data from the 2011 Global Gender Gap report, Figure 1 shows that while India scores around the mean gender gap index overall (horizontal axis), its score for women’s economic participation and opportunity is below the 5th percentile of the distribution (vertical axis).

What explains these huge gender disparities in women’s economic participation in India? Is it poor infrastructure, limited education, and gender composition of the labor force and industries? Or is it deficiencies in social and business networks and a low share of incumbent female entrepreneurs?In a recent paper we examine gender disparities in women’s business conditions in India. We use detailed micro-data on the unorganized manufacturing and services sectors to explore the drivers of female entrepreneurship across districts and industries.

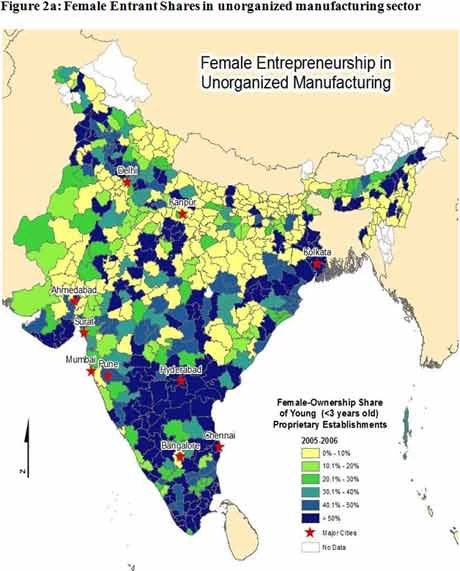

The good news is that the overall India average female business-ownership share has improved over time from 26% in 2000 to 37% in 2005. On an employment-weighted basis, the rate has increased from 17% to 25%. Figures 2a and 2b show, however, that there is wide variation across states in the role of women in local entrepreneurship.

Which industries attract female entrepreneurs? Within the manufacturing sector, female shares are highest and typically exceed 50% in industries related to paper and tobacco products. At the opposite end, female shares of 2% or less are evident in industries related to computers, motor vehicles, fabricated metal products, and machinery and equipment. In services, female ownership rates in major cities tend to be higher than overall state averages and exceed 30% in industries related to sanitation and education. Industries related to research and development, and transportation have the lowest rates at 1% or less.

Main Results

The focus of our analysis is on the extent to which local industrial conditions (e.g., Glaeser and Kerr 2009) influence the gender balance of new enterprises. We develop metrics that condense complex local industrial structures into simple indicators of the suitability of a given area for an industry in terms of local labor force compatibility or input-output connections. We develop these metrics separately using female- and male-owned incumbent businesses to identify how gender-specific agglomeration benefits are for new entrants.1

Table 1 summarizes our primary results. The outcome variable is the female-run young establishments share in the district-industry. These estimations control for industry-year fixed effects. Our working paper describes results that use more rigorous models and instrumental variable strategies that confirm these findings.

Note: Coefficient direction and significance level shown. “+++” implies positive coefficient significant at the 1% level. Two and one +/- signs imply 5% and 10% significance, respectively.

We find that a district-industry with more incumbent female employment has a greater female entry share. Among district-level traits, a higher female-to-male sex ratio, a higher working-age to non-working age population ratio (demographic dividend), better quality infrastructure, and more stringent labor regulations appear important. The relative female entry rate declines with high population density. Education and female literacy rates are not associated with gender differences in manufacturing.

The infrastructure correlation is the most policy relevant. Inadequate infrastructure affects women more than men, perhaps because women often bear a larger share of the time and responsibility for household activities. It is notable that while the within-district infrastructure access is prominent, access to major cities is not found to influence the gender balance. Additional work finds that transport infrastructure and paved roads within villages are especially important. Travel in India can be limited and unpredictable, and women face greater constraints in geographic mobility imposed by safety concerns and/or social norms. Better transport infrastructure may alleviate a major constraint for female entrepreneurs accessing markets.

The agglomeration metrics suggest that female connections in labor markets and input-output markets contribute to a higher entry share. A one-standard deviation increase in either of these incumbent conditions correlates with a 2%-3% increase in the share of new entrants that are female. This compares to a base female entry ratio of 21%. Most of the basic district-level linkages observed for manufacturing continue for services. Somewhat surprisingly, a higher female entry ratio is not associated with a greater female sex ratio in the district, but female literacy rates and general education levels are more predictive. This link may be due to services being more skill intensive than manufacturing in India. Stronger female-owned incumbent businesses again predict a greater female entrepreneurship in service industries.

Policy Implications

A central driver of economic growth over the past century is the increased role of women. This growth in the role of women comes in many forms: better education and health that increase female labor force participation, reduced discrimination and wage differentials that encourage greater effort, and improved advancement practices that promote talented women into leadership and managerial roles. Simply put, empowering half of the potential workforce has significant economic benefits beyond promoting gender equality (Duflo 2005, 2011; World Bank 2012).

Infrastructure and education predict higher female entry shares in India. We find evidence of agglomeration economies in both manufacturing and services, where higher female ownership among incumbent businesses within a district-industry predicts a greater share of subsequent entrepreneurs will be female. Moreover, higher female ownership of local businesses in related industries (e.g., similar labor needs, input-output markets) predict greater relative female entry rates even after controlling for the focal district-industry’s conditions.

Gender networks thus clearly matter for entry into entrepreneurship. However, we need to develop a better understanding of how gender networks influence aggregate efficiency. An important message of our paper is that these linkages and spillovers across firms can depend a lot on common traits of business owners. Likewise, interactions between the informal and formal sectors may not be as strong as interactions within each sector. Further research needs to identify how these economic forces vary by the composition of local industry. This will be especially helpful for evaluating the performance of industry concentrations in developing economies and guiding appropriate policy actions.

Recent work emphasizes the role of women in development. India’s economic growth and development depends upon successfully utilizing its workforce, both male and female. Despite its recent economic advances, India’s gender balance for entrepreneurship remains among the lowest in the world. Improving this balance is an important step for India’s development and its achievement of greater economic growth and gender equality. While achieving economic equality sometimes requires tough choices (e.g., progressive taxation that may discourage effort), the opposite is true here.

(The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily The World Bank or any other institution they may be associated with)

1 Ghani et al. (2011a) and Mukim (2011) consider many of these district factors and industrial conditions in their studies of general rates of entrepreneurship across India. Our work in this paper focuses specifically on explaining the gender balance of entrepreneurship. Beyond this direct application, we apply in the local industrial conditions framework a sub-population like gender, and our results suggest this is an attractive avenue for future research.

Join the Conversation