Economists could draw inspiration from such wisdom: No matter how bad existing conditions in a low-income country are, there are always some areas they can do relatively well. It is much better to identify these areas and scale them up, than to spend time listing all the missing conditions for doing something that they are not good at. Such conditions are often in the image of an idealized advanced economy. Sounds obvious? Unfortunately the history of the discipline shows that researchers have not yet embraced Sir Paul’s optimism.

The first wave of researchers working on low-income countries, which emerged after WWII, focused on structural change by promoting the development of advanced modern industries. They thought the absence of such industries in poor countries was due to market failures and recommended a state-led import-substitution strategy - many of which failed due to inherent distortions in that strategy. By the 1980s, a second wave led a gradual shift to free market policies, culminating in the Washington Consensus, advocating stabilization, liberalization and privatization. It assumed structural change would happen spontaneously as long as markets remained free. Its results were also disappointing.

Despite stark differences in their theoretical foundations, the first two waves of thinking both held up advanced economies as the paragon for poor economies and built their policy frameworks based on the elements that the latter were missing (advanced industries, good business environment and governance, strong human capital, etc.).

I propose to start a third wave --“Development Economics 3.0”, motivated by the success of initially poor countries in Asia and other parts of the world, which aims to refocus on economic transformation. In doing so, the third approach, which I call New Structural Economics (NSE) in my recent book, is consistent with Sir Paul’s optimistic stance. NSE holds that, no matter how bad its current economic situation is, any poor country has sectors that are consistent with its comparative advantage (that is, what they can do well) based on their existing endowments. The government can help private firms scale up those sectors and become competitive in domestic and international markets. In the process of structural change the country can also exploit the benefits of backwardness to achieve sustained dynamic growth.

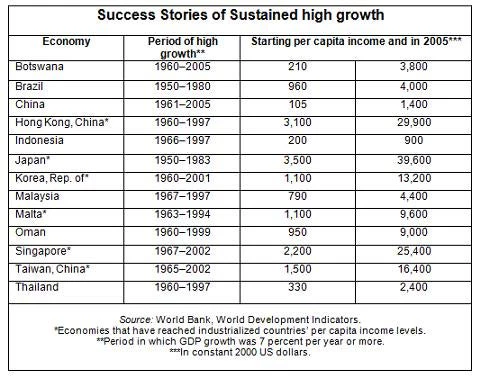

NSE draws on lessons from success, a method taken up by the Growth Report of Michael Spence and others. Their report pinpoints which economies recorded multiple decades of growth in the postwar period. Thirteen economies qualify: Botswana; Brazil; China; Hong Kong, China; Indonesia; Japan; the Republic of Korea; Malaysia; Malta; Oman; Singapore; Taiwan, China; and Thailand.

These cases demonstrate that fast, sustained growth is possible. According to Spence and his Commission colleagues, these economies share five traits. First, they are open. Second, they maintained macroeconomic stability. Third, they mustered high rates of saving and investment. Fourth, they let markets allocate resources. Fifth, they had committed, credible, and capable governments. In fact, the last two are the preconditions for a country to follow its comparative advantages and the first three are the results of doing so.

The ideal industrial structure emerges when all industries are consistent with an economy’s comparative advantages and are competitive in domestic and international markets. Macro stability, high savings and fast capital accumulation ensue, the endowment structure and comparative advantages shift, and eventually it is necessary to upgrade the economy’s industrial structure to a more capital-intensive level. This evolution requires changes in hard (physical) and soft (institutional) infrastructure to reduce transaction costs. Upgrading is inherently beset by outside obstacles and coordination issues that cannot be fixed by individual firms alone, therefore the government needs to play a proactive facilitating role.

At its heart, development economics should be about supporting low-income country governments to set up effective policy frameworks and design interventions that allow the private sector to develop competitive industries and tap into the latecomer advantages. That is the open secret of dynamic and inclusive growth.

Join the Conversation