“I know there’s a bad reputation out there in some circles about online courses,” says Frisch, an instructor who teaches online courses in the Speech Department at Central Lakes College, a two-year community college in Brainerd, Minn.

But Frisch says she is motivated by the criticism of online courses, deemed to be ineffective and more prone to being dropped by students.

“That damaging stereotype is, in part, what kept driving me to do what I could to make my course something to be proud of and that would make a positive difference in students’ lives, not just academically,” explains Frisch, who has been teaching online courses at Central Lakes College since 2009.

Evidently, Frisch’s work is paying off.

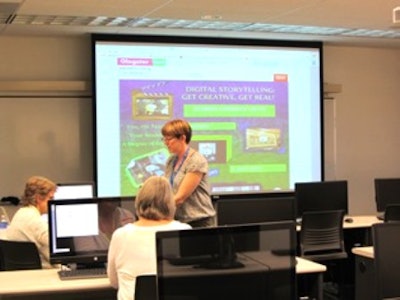

At a time when questions remain about the value and effectiveness of online education, Frisch is increasingly being called on to give presentations on how to keep students engaged in online courses for the long haul.

For instance, last month, Frisch presented at the 7th Annual Emerging Technologies for Online Learning International Symposium. The event is staged by the Sloan Consortium, an organization that advocates for the mainstreaming of online education.

The title of Frisch’s presentation, “How’d You Do That? Tips and Tricks That Might Account for My 95 Percent Retention Rate,” drew from the fact that attrition in her courses is 3.9 percent—well below the 10.08 and 6.02 percent attrition rates for online and land-based courses, respectively, on her campus.

Tips from Frisch’s presentation include:

• Setting firm but reasonable deadlines. In Frisch’s courses, for instance, she shuns the “midnight” deadlines and instead sets two due dates for assignments—at 1 p.m. on Wednesdays and Fridays—to make sure that online technical support is available in case students need assistance. “If the procrastinators have technical issues, who is there to help?” Frisch asks. “Weekday deadlines also ensure that students have adequate time during the week to complete work.

• Releasing course information weekly to keep students engaged but not overwhelmed.

• Using a variety of assignments—from having students watch or create videos to doing interpersonal interviews—to keep students engaged and connected to the content.

Frisch, who chairs the Online Instruction and Technology Council, says her presentation grew out of various experiences she has had teaching students from diverse backgrounds. That experience has led to a heightened awareness of potential obstacles for students who face different challenges.

For instance, Frisch makes it a point to release new information at the top of the content instead of at the bottom—a practice she described as more sensitive to standards of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

“This way, they don’t have to scroll down to find new material,” Frisch says, explaining that students with disabilities who use software programs called “readers” won’t have to scroll down to get to the current information for the course.

Frisch also opted to break away from the practice of timed tests—a move she says has been appreciated by various students, including those who suffer from ADHD and those with children.

She also allows open-book tests—and admits she’s a little uneasy about how she will be seen by colleagues for allowing the practice.

“When I travel around doing this presentation, I still get a little nervous presenting that point as if I’m going to be attacked for being ‘a bad teacher’ for not following patriarchal pedagogy,” Frisch says.

But, she adds, “I think this way works for many of my diverse types of students.”

The reality is Frisch and proponents of online education would face criticism regardless, and there’s plenty of ammunition for critics.

For instance, community colleges typically see course withdrawal rates of 20 to 30 percent, with high withdrawal rates for online courses, according to an April 2013 report by the Community College Research Center (CCRC) at Teachers College at Columbia University.

“Course persistence and completion is a particularly important issue in community colleges, where most students are low-income, many are working or have dependents, and few can readily afford the time or money required to retake a course they did not successfully complete the first time,” states the CCRC report, titled “Examining the Effectiveness of Online Learning Within a Community College System: An Instrumental Variable Approach.”

That is certainly the case at Central Lakes College, where 63 percent of all full-time, first-time, degree- or certificate-seeking undergraduate students rely on Pell grants, and 60 percent rely on federal student loans, according to a federal database.

Raising concerns

Beyond issues of retaining students, critics also raise concerns about whether online education provides effective ways to learn and whether it affords students the personalized attention they deserve.

Those issues were debated earlier this month at an Intelligence Squared U.S. Debates event, titled “More Clicks, Fewer Bricks: The Lecture Hall Is Obsolete,” at Columbia University.

One of the debaters was Anant Agarwal, MIT professor and president of Harvard and MIT’s edX—a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) that enables students from around the world to experience courses at MIT, Harvard, Berkeley and other universities. Agarwal spoke of students from around the world who enrolled in classes in order to improve their lives.

Jonathan Cole, provost and dean emeritus at Columbia University and author of The Great American University, argued that there is no evidence of a “democratizing” effect of online education.

“Who in fact takes those courses from all over the world?” Cole asked. “The people who take those courses are people who are already educated.”

Cole also said there is a need for students and instructors to interact and deal with complex subject matter.

Ben Nelson, founder and CEO of Minerva Project, an online learning initiative that involves small interactive video seminars and group discussion, countered Cole, saying, “The close conversation between students and professor in small groups that explore subject matter, it turns out you can do that online as well and you can do it in a [better] way.”

Frisch has no shortage of examples of how she facilitates interaction with her students online and fosters a sense of connectedness. Espousing a “one-degree-of-separation” philosophy in her course on intercultural communication, Frisch uses a video of her interviewing a Buddhist monk and a video of a series of photos from a Norwegian wedding in which she served as the maid of honor.

“Oftentimes, ideas in textbooks seem so ‘removed’ from what students think their life is,” says Frisch. “So bringing it closer makes it hopefully more ‘real,’ more interesting, more engaging.

“Students report that, since they’ve seen me share my travel experiences and know that I, too, was once a student here at CLC, they feel maybe there’s hope for them that one day they, too, could travel and have experiences they wouldn’t otherwise have.”