This is the sixteenth in our series of posts by students on the job market this year.

The importance of history in economic development is well-established (Nunn 2009; Spolaore and Wacziarg 2013), but less is known about the specific channels of transmission which drive this persistence in outcomes. Dell (2010) stresses the negative effect of the mita (mining labor system) in Latin America, and Nunn and Wantchekon (2011) document the adverse impact of African slavery through decreased trust. But might other colonial arrangements lead to positive outcomes in the long run?

I address this question in my Job Market Paper by analyzing the long-term economic consequences of European missionary activity in South America. I focus on missions founded by the Jesuit Order in the Guarani lands, in modern-day Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. This case is unique in that Jesuits were expelled from the Americas in 1767 and never returned to the Guarani area, thus precluding any direct continuation effect. While religious conversion was the official aim of the missions, they also increased human capital formation by schooling children and training adults in various crafts. My research question is whether such a one-off historical human capital intervention can have long-lasting effects.

Key Findings

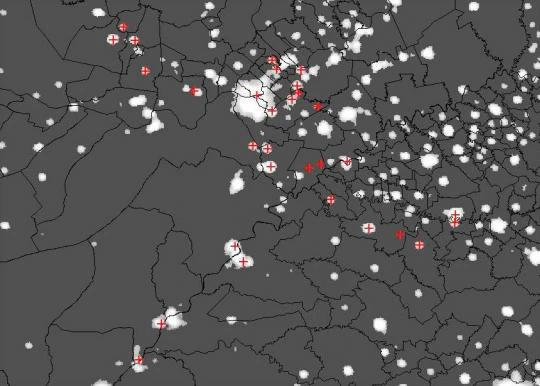

Using municipal level data for five states (Corrientes and Misiones in Argentina, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and Itapúa and Misiones in Paraguay), I find substantial positive effects of Jesuit missions on human capital and income, 250 years after the missionaries were expelled. In municipalities where Jesuits carried out their apostolic efforts, median years of schooling and literacy levels remain higher by 10-15%. These differences in educational attainment have also translated into higher modern per capita incomes of nearly 10% (as can be seen in the Figure, using nighttime satellite data). I then analyze potential cultural mechanisms that can drive the observed results. To do so I conduct a household survey and lab-in-the-field experiments in Southern Paraguay. I find that respondents in missionary areas have higher non-cognitive skills and more pro-social behavior.

Note: The maps depict the nighttime satellite images of the Guarani Jesuit missionary areas, other areas, and municipal level boundaries for the states of Corrientes and Misiones (Argentina), Itapua and Misiones (Paraguay) and Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil), denoting the location of the Guarani Jesuit Missions (red crosses).

Setup

To disentangle the national institutional effects from the human capital shock the missions supplied, I use within country variation in missionary activity in three different countries. The area under consideration was populated by the same semi-nomadic indigenous tribe, so I can abstract from the direct effect of different pre-colonial tribes (Maloney and Valencia 2012; Michalopoulos and Papaioannou, 2013). The Guarani area also has similar geographic and weather characteristics, though I control for these variables in the estimation.

Endogeneity

Even though I use fixed effects and geographic controls, Jesuit missionaries might have chosen favorable locations beyond such observable factors. Hence the positive effects might be due to this initial choice and not to the missionary treatment per se. This does not appear to be the case using Altonji ratios (Altonj et al. 2005), which suggest that selection on unobservables would have to be more than four times larger than selection on observables to drive the results.

Still, to address the potential endogeneity of missionary placement, I conduct two empirical tests. The first one is a placebo that looks at missions that were initially founded by the Jesuits but were abandoned early on (before 1659) mostly due to attacks by Portuguese bands or bandeirantes (I also analyze the attacks themselves in a separate section in the paper). I can thereby compare places that were initially picked by missionaries with those that actually received the missionary treatment. I find no effect for such “placebo” missions, which suggests that what mattered in the long run is what the missionaries did and not where they first settled.

Second, I conduct a comparison with the neighboring Guarani Franciscan Missions, which were founded even earlier from 1580 to 1615. The comparison is relevant in that both orders wanted to convert souls to Christianity, but Jesuits emphasized education and technical training in their conversion. Contrary to the Jesuit case, I find no positive long-term impact on either education or income for Franciscan Guarani Missions. This suggests that the income differences I estimate are likely to be driven by the human capital gains the Jesuits provided.

I also employ an IV strategy, where I use as instruments the distance from early exploration routes and distance to Asuncion. Distance from the exploration routes of Pedro de Mendoza (1535-1537) and Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca (1541-1542) serves as a proxy for the isolation of the Jesuit missions (in the spirit of Duranton et al. 2014). Asuncion, in turn, served as a base for missionary exploration during the foundational period, but became less relevant for Rio Grande do Sul after the Treaty of Madrid (1750) transferred this territory to Portuguese hands. For this reason and to avoid the direct capital – and Spanish Empire – effects, I use this variable only for the Brazilian subsample of my data (as in Becker and Woessmann 2009; Dittmar 2011). The first-stage results are strongly significant throughout (with F-statistics well above 10), and the coefficients for literacy and income retain their sign and significance – appearing slightly larger – in the IV specifications.

Extensions and Mechanisms

Using historical censuses I am able to trace the human capital effect through the intervening period between the missionary era and today. I use data from the 1895 Census of Argentina, the 1920 Census of Brazil, and the 1950 Census of Paraguay. I find that Jesuit missions had an even larger effect on human capital during intermediate historical periods and that these effects are concentrated on local inhabitants rather than foreigners, as expected.

To complete the empirical analysis, I examine cultural outcomes and specific mechanisms that can sustain the transmission of human capital from the missionary period to the present. I find that respondents in missionary areas possess superior non-cognitive abilities, as proxied by higher “Locus of Control” scores (Heckman et al., 2006). Using standard experiments from the behavioral literature, I find that respondents in missionary areas exhibit greater altruism, more positive reciprocity, less risk seeking and more honest behavior. I use priming techniques to further investigate whether these effects are the result of greater religiosity – which appears not to be the case.

In terms of mechanisms, I find that municipalities closer to historic missions have changed the sectoral composition of employment, moving away from agriculture and towards manufacturing and services (consistent with Botticini and Eckstein, 2012). In particular, I document that these places still produce more handicrafts such as embroidery, a skill introduced by the Jesuits. People closer to former Jesuit missions also seem to participate more in the labor force and work more hours, consistent with Weber (1978). I also find that indigenous knowledge — of traditional medicine and myths — was transmitted more from generation to generation in the Jesuit areas. Unsurprisingly, given their acquired skills, I find that indigenous inhabitants from missionary areas were assimilated differentially into colonial and modern societies. Additional robustness tests suggest that the results are not driven by migration, urbanization, or tourism.

Limitations

Though I scrutinize the case of Jesuit Missions in the Guarani area, it would be interesting to assess the external validity of my results in other contexts. I focus on human capital and rule out other channels of transmission, but pre-existing power structures, attitudes towards foreigners and collective action mechanisms may still be playing a role in my findings. In terms of data, due to financial constraints, my household survey only covers the Paraguayan area, but I am planning to extend it to Argentina and Brazil in the future.

Policy Implications

Though one has to be careful when extrapolating policy implications from historical studies, there are important lessons to be learnt from the Guarani Jesuit Missions. The findings support the view that investments in human capital can have very long-lasting consequences by altering the culture of communities and individuals. This adds to the public finance debate on how to allocate scarce government resources, while being aware of the differences observed could aid governments to better target their educational and labor training programs. Far from advocating historical determinism, a thorough understanding of these historical forces offers the opportunity to make development policies more targeted and effective.

Felipe Valencia is a Job Market candidate at Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Join the Conversation