"Writing laws is easy, but governing is difficult," wrote Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace. We agree.

Our recently finished study highlights how differences in the enforcement of a strict labor code across Russia’s numerous administrative regions has affected hiring and firing decisions. More specifically, we examine how the varying capacity to enforce the labor code affected labor adjustment by firms in response to industry-wide surges and slumps.

Such adjustment is part of the all-important churn of jobs needed to adapt to the frequent and vertiginous ups and downs that characterizes the Russian economy. It is important to point out that the data used in the preparation of the note date back a few years and does not reflect current conditions. Russia has been an aggressive and successful regulatory reformer in recent years. However, these data from the recent past are interesting for policymakers because it emphasizes the need to pay attention to the implementation and enforcement of reforms as well as their design.

The growing body of research on the impacts of labor laws largely ignores how well they are enforced. But enforcement capacity can be variable in low and middle income countries. A case in point is Russia: some regions in Russia have the capacity to enforce their labor regulations more stringently than others. One way to tell is by looking at the ratio of labor inspectors per hundred thousand covered employees. This ratio varies from a minimum of 11 to a maximum of 50 employees per inspector across regions. Similarly, the capacity of courts to handle labor disputes also varies across regions.

During the time period these data cover, regulatory enforcement seemed weak in Russia; for example, its score in the World Justice Project’s Effective Regulatory Enforcement Index is 0.5, while most high-income countries have a score near 0.8. At that time, Russia’s labor code was relatively strict, especially when it comes to letting go of workers. According to the Doing Business report, during 2006-2009, Russia was approximately in the bottom third of countries in terms of costs and other restrictions imposed on firms making changes to their labor force (World Bank, 2010)[1] Those Doing Business reports indicate that Russia’s labor code requires that when a worker is declared redundant, that worker must be paid 13-14 weeks’ worth their salary. It is also difficult to hire workers on fixed term or flexible contracts. Fixed term contracts are prohibited for permanent tasks, and the maximum length of fixed term contracts is 60 months, while other flexible forms of labor contracting are restricted or not allowed. We stress again that in recent years, Russia has made improvements to its labor code and made it easier for companies to start a business. This study is based on available data from 2010 to look generally at the impact of weak enforcement on strict labor laws. While the study is recently released, the data is not.

A strict labor code is expected to mute the hiring and firing of workers in response to changing economic fortunes. Because it imposes high firing costs on firms, it should dampen layoffs during downturns. The strict labor law, which prohibits flexible term contracts, is also expected to force firms to be more cautious about hiring in upturns. This is because firms would worry about having to lay off workers hired during an upsurge when conditions turn leaner.

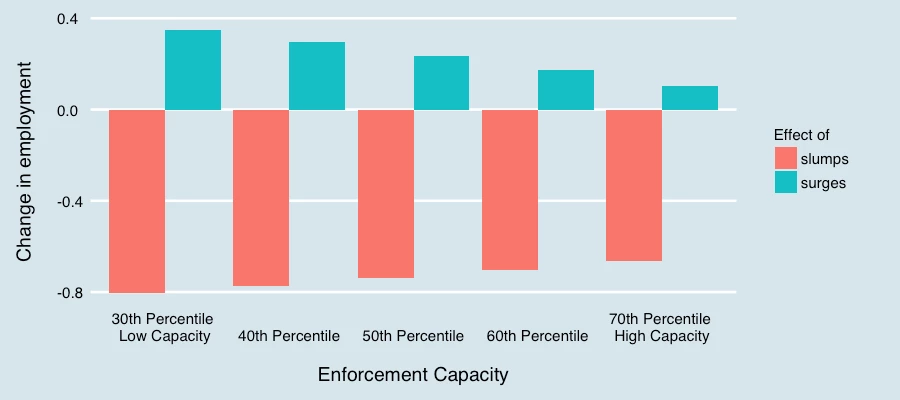

The point we make in this paper is that while the law may be strict, its enforcement is what matters to firms as they make hiring and firing decisions. In administrative regions where enforcement capacity is compromised, the strictness of the labor code is less binding and firms can hire and let go of workers as if a more lenient labor code was in place. The opposite is the case when enforcement capacity is high. Here, the contracting and the shedding of workers is expected to be relatively more muted.

We found that the extent to which firms hire during industry upswings and let go of workers during down swings is smaller in regions with stronger enforcement capacity (or, stricter de facto employment protection). The effect of enforcement is sizable: for example, increasing enforcement capacity from the 25th to the 75th percentile dampens employment adjustment in a downswing by 34%. Thus, while restrictive regulation on hiring and firing reduces the ability of firms to adjust employment, the extent to which it does so depends on enforcement.

Reforming draconian labor laws is important for bringing about more efficient labor reallocation. However, one implication of our result is that a reduction in the stringency of labor regulations might have unexpectedly small impact in places where the existing law is already weakly enforced. Moreover, to the extent that enforcement capacity is weaker in poorer countries, we run the risk of attributing too much blame to their stringently formulated labor laws. We also risk being too complacent about regulations that look good on paper but are not well-enforced.

Our study thus underlines the importance of including regulatory enforcement more comprehensively in the research agenda on productivity and growth in low and middle income countries. The role of institutional enforcement capacity in determining the effectiveness of regulations–and its measurement–is another largely untapped field of research.

Follow the World Bank Jobs Group on Twitter @wbg_jobs.

Join the Conversation