Leah is a diligent 13-year-old student in rural Liberia. She walks to the school near her village every day. She pays attention in class. She hopes to be a teacher one day. Yet, there is a problem. Leah is still in first grade.

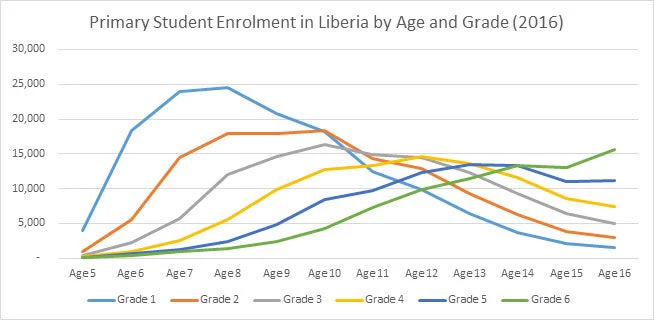

Her case isn’t an isolated one. Almost all Liberian students (82% of students in primary school) are too old for their grade. In fact, the average first grader in Liberia is 9 (three years older than the appropriate age for a first grader).

Causes of over-age enrolment

Like many post-conflict countries, ripples from the civil war are being felt in Liberia to this day. During the conflict, children had to emigrate to neighboring countries to continue their education, depend on makeshift community schools or temporarily stop their education. As a result, especially at the secondary education level, over-age enrolment has continued to remain a civil war legacy.

However, that’s a transitory part of the present story. There are other more fundamental and persistent challenges that are pertinent for younger children in Liberia. Primary education in public schools is free. However, early childhood education (ECE) is not. Also, because of stunting and malnutrition, some children may not be ready for first grade. Schools, therefore, have both incentives and justification to keep children in early childhood education programs and enroll over-age children in ECE programs rather than in primary.

There are economic and social reasons as well. Parents have to save up money to send their children to school and it takes time to save enough to pay the fees for ECE (approximately $35 per year), and the costs for transportation and uniform.

Liberia’s Household Income and Expenditure Survey data (2014 – 15) reveals that, if schools are far from people’s homes, parents feel worried about sending their young children on foot and prefer to hold them back for a few years. Also, school-aged children are sometimes required to babysit their toddler siblings or do household chores. Girls bear a disproportionate burden as parents are far more likely to hold back their daughters from schools as compared to their sons.

Progress

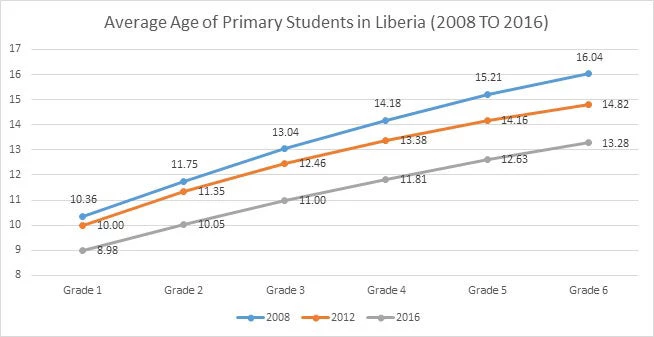

The problem of over-age enrolment isn’t as severe as it used to be even about a decade ago. As the chart below shows, the average first grader in 2008 was more than 10 and the average sixth grader was 16. Improvement has been gradual but continuous as the impact of the civil war has receded.

Yet, the issue of over-age enrolment isn’t going away because the fundamental challenges in the education sector remain. And so, this remains a matter of priority for the Ministry of Education and its development partners.

Over-age children are more vulnerable and at greater risk of dropping out either because they get dissuaded or because they are pulled into the labor market to financially support their family. Girls, in particular, are at even greater risk due to teenage pregnancy, early marriage or being approached for transactional sex in return for grades.

Moreover, teaching a teenager and teaching a young child require different pedagogical approaches and pose additional challenges for teachers in already crowded classrooms.

Addressing the problem

It is still better to send children to school even if they are over-age. The benefits are not just measured in education attainment and literacy, but in other skills such as better family health and better attitudes towards educating one’s own children.

On the demand side, changing the perception of parents remains key to tackling this issue. We have both global and Liberia-specific evidence that educating/training parents (especially mothers) leads to better attitudes about sending their own children to school. For instance, the Economic Empowerment of Adolescent Girls and Young Women (EPAG) Program, a World Bank project focused on improving incomes for adolescent girls, has not only led to higher incomes but has also changed young mothers’ attitudes about sending their own children to school.

Creating other individual and household incentives (like conditional cash transfers) is difficult because of budget constraints in a post-conflict country. The Ministry of Education and the World Bank, under the auspices of the Global Partnership for Education, have recently started work on identifying cost effective ways of reducing and eliminating ECE fees, particularly for disadvantaged and rural communities. At the same time, the sudden reduction or elimination of ECE fees may lead to a substantial increase in demand that public schools may not be able to meet.

On the supply side, the government has focused on the provision of alternative education programs to absorb over-age students and accelerate their learning through parallel education programs. Efforts to improve school sanitation, hygiene and student safety are also underway and need to remain a priority.

Pratham (India) and the Teacher Community Assistant Initiative (Ghana) have shown that innovations like remedial lessons for over-age and other vulnerable students need not be expensive or difficult. We are also working towards providing greater support to teachers and schools to be able to cope with children in the same classroom of different ages and at different grade levels.

There are no easy solutions. For Leah’s sake, and that of more than a million children like her, combatting over-age enrolment will remain an important priority for the joint effort between the Liberia and the World Bank.

Find out more about the World Bank Group’s work on education on Twitter and Flipboard.

Join the Conversation