Tatsumi Yoshihiro, one of comics history’s greats, passed away on March 7, 2015. He was seventy-nine years old. He died of malignant lymphoma.

Tatsumi is famous as the artist who helped fashion a new style of manga known as “gekiga” (dramatic pictures), a term he coined in 1957. He played a major role in broadening the possibilities of the medium to accommodate mature-reader genres like mystery, action, and horror, oftentimes in 100-plus-page, single-story books that predate the advent of the “graphic novel” by many decades. Though there was hardly a genre Tatsumi didn’t try his hand at, he is best known for the stories he created in the late '60s and early '70s about the bleak lives and perversions of aging white-collar and low-level blue-collar workers. French and Spanish translations of these stories in the early '80s first introduced Tatsumi’s work to an outside audience. But the artist’s star took off like a comet only with new and expanded editions of this material in Japanese and English in 2004-05. A Drifting Life (2008-09), his massive 850-page autobiography in comics form, cemented Tatsumi’s reputation as one of the comics medium’s most important artists. Late in life, Tatsumi was awarded three of the industry’s top awards: a special prize at Angoulême (2005), the Tezuka (2009), and the Eisner (2010).

Born on June 5, 1935, Tatsumi grew up primarily in Toyonaka City on the northern outskirts of Osaka. Like many of his generation, Tatsumi was a passionate fan of the work of Tezuka Osamu and the magazine Manga Shōnen. Already at the age of fifteen, Tatsumi was frequently publishing four-panel humor strips in national manga magazines and regional children’s newspapers. In March 1954, his first book, Children’s Island (Kodomo jima), a Treasure Island-type tale for kids, was published by Tsuru Shobō in Tokyo.

It was within the rental kashihon market in Osaka, however, that Tatsumi made history. His fate was sealed later in 1954 upon submitting an unpublished manuscript, a riff on Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin and Edogawa Ranpo’s Youth Detective League, to Yakkō Publishing (more popularly known as Hinomaru Bunkō) in Osaka. Numerous mystery, humor, and martial arts titles followed, establishing Tatsumi as one of Hinomaru’s leading talents, alongside Matsumoto Masahiko and Saitō Takao, also luminaries-to-be. Having come of age amidst the ruins and hardships of a defeated Japan, and steeped in the decadent Americanized entertainment of the postwar period, these cartoonists could not bring themselves to uphold the model of existing children’s comics. They saw a field dominated by frivolous slapstick, an over simplistic division between good and evil, and flights of fantasy at the expense of contemporary Japanese actuality.

For something new, they turned to the psychological dramas, moral ambiguities, and violence of contemporary detective fiction and suspense films. They envisioned a readership older than the grade school students who typically consumed manga as an after-school snack. A new visual language was required, one based in the breakdown methods and character animation of Tezuka’s work, on which they all had been weaned, but less reliant on humor and looser in its handling of form. It was Tatsumi’s name for this new genre of adolescent comics that stuck: “gekiga,” meaning “dramatic pictures.” Though Tatsumi only began presenting his stories under that rubric in 1957, it was a full-length book published in November 1956 titled Black Blizzard (Kuroi fubuki), about a piano player wrongly convicted of murder and his desperate flight from the police through the snow, that the artist later identified as the epitome of this new gekiga style. This 128-page flurry of expressionistic lines and anxiety-ridden breakdowns was drawn in a mere twenty days.

The gekiga style caught on like wildfire. Within a couple of years, most artists working in the mystery genre were using the term and a Tatsumi-inflected language. One publisher after another began emulating the detective anthologies Tatsumi contributed to, namely Shadow (Kage, founded in 1956) and The Street (1957). For a time, Tatsumi edited these and similar publications, thus shaping the manga scene not only as an artist but also as a mentor and curator.

In 1959, Tatsumi and many of his peers moved to Tokyo to be closer to the big publishing houses. There, he helped form the Gekiga Studio (Gekiga Kōbō), an artist-run publishing collective based on profit-sharing and editorial control, with a view ultimately to self-publish. Amongst the many publications produced by the Gekiga Studio was the mystery and gangland anthology Skyscraper (Matenrō) from Togetsu Shobō. The organization was short-lived, disbanding after just six months, but its influence was great. It catalyzed the formation of some of the manga industry’s first formal production studios. Its publications established its contributors’ reputations in Tokyo, paving the way for the creation of their own (again short-lived) publishing houses and subsequently their move into the big time of mass print magazines.

The early-mid '60s, however, were a period of hardship for Tatsumi and his peers. Their mothership, the kashihon market, was rapidly sinking. Designed to provide entertainment at an affordable price to kids regardless of their economic situation, rental bookstore chains found their clientele disappearing as Japan got richer and children gained the luxury to buy rather than rent their entertainments. There was also new competition from free-to-watch television and, its partner in print, the cheap, weekly, newsstand manga magazines. In the early '60s, Tatsumi continued producing dark and inky stories culled from the world of hardboiled fiction and Nikkatsu Action-type films. Iconic amongst the many titles were Dynamic Action and Tatsumi Yoshihiro Action, both published by Sanyōsha, which would later become Seirindō, the future publisher of Garo. Amongst the many gangland stories he made in this period, there are many starring precocious boxers compromised by family poverty and underworld connections. Tatsumi himself had also recently taken up boxing.

In 1963, Tatsumi founded Dai’ichi Pro (Number One Productions), his own publishing house. It would later be renamed Hiro Shobō, and continued until 1971. Its catalogue is a clear indication that the leader had become the follower. The best known title from Dai’ichi Pro has nothing to do with gekiga: Youth (Seishun), a semi-monthly romance anthology for high school students. His own work for Dai’ichi and Hiro Shobō, while harboring some gems, comprised mainly knock-offs of the style and types of former kashihon peers who had successfully moved into magazines: Saitō Takao’s playboy detectives, Mizuki Shigeru’s suburban yōkai, and Shirato Sanpei’s violent ninja. Tatsumi also published many rewrites of his own work from earlier in the decade – another sure sign that the artist had lost steam.

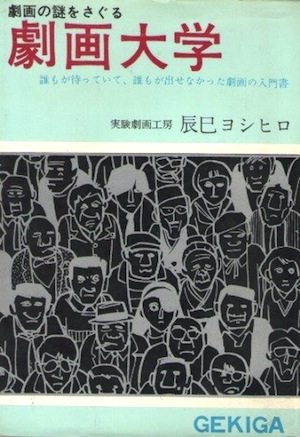

Adding insult to injury, by the mid '60s Tatsumi had completely lost control over the term “gekiga.” The name was used to describe pretty much anything that was action-based for young men. This is important to remember when considering Tatsumi’s popularity in recent years. Most Japanese men have read lots of “gekiga,” but these are mainly by artists like Saitō Takao, Kamimura Kazuo, and Kojima Goseki, and their latter-day descendants in the '70s and '80s. Tatsumi might have respected these artists, but he found in mainstream “gekiga” a corruption of what he intended for that term. In 1967, he self-published Gekiga College (Gekiga daigaku) to set the record straight. Its texts and interviews presented a set of normative principles of what gekiga was intended to be: cinematic, for an older audience, realistic in terms of setting and character, no humor. The book was highly influential, and became a foundational text for the critics of the small self-published coterie magazine Manga-ism, founded in 1967. It was they, circa 1970, who first framed Tatsumi and kashihon gekiga as the beginning of an “alternative” comics lineage and an authentic popular cultural expression of the pre-high economic growth '50s.

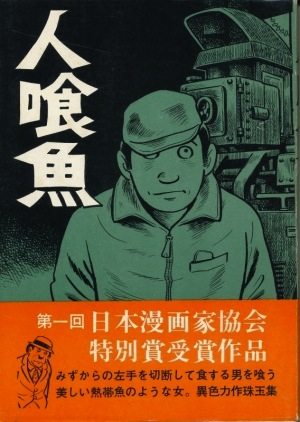

The stories translated in Push Man and the other D&Q volumes were made soon after Gekiga College. Some of these were first published in an obscure, B-grade magazine named Gekiga Young in 1968. Others appeared in Garo, a magazine with strong roots in the kashihon past. In 1971, Garo honored Tatsumi with a special issue dedicated to his work. The best-selling Weekly Shōnen Magazine also gave Tatsumi a shot, but he was purportedly blacklisted after sales dropped following the inclusion of his bleak narratives. Nonetheless, a collection of these stories titled The Man-Eating Fish (Hitogui zakana, 1970) landed the artist a prize from the Japan Cartoonists’ Association in 1972. These stories are ostensibly Tatsumi’s attempt to reclaim “gekiga” from the culture industry. This he succeeded in doing, though it took almost four decades and the help of foreign publishers, such that now, outside Japan at least, “gekiga” is practically synonymous with the artist’s name.

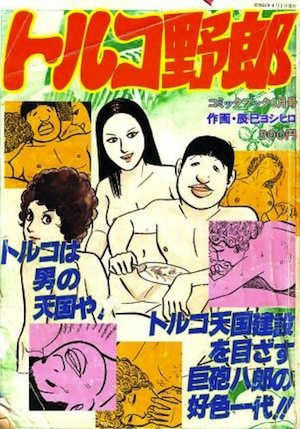

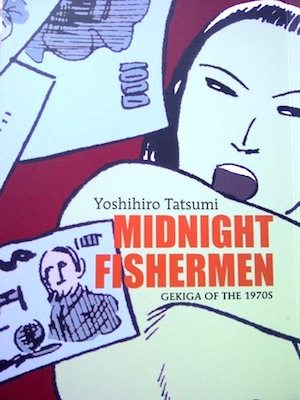

Back in the '70s, however, Tatsumi was struggling to keep his head above water. He tried to continue the short story magic, but after 1972 his vignettes fizzle. One is grateful that some of these have been made available in English in Midnight Fishermen, from Singapore’s Landmark Books (2013), but the content definitely pales against the classic 1968-72 work found in the D&Q trilogy. Meanwhile, the definition of gekiga slipped ever further from Tatsumi’s grasp. As the men’s comics industry was virtually saved from dissolution by shifting increasingly to pornography, so “ero” (as in “erotic”) became a standard prefix appearing before “gekiga.” Ask your average Japanese person today the meaning of “gekiga,” and many will respond by saying something like “pornographic comics for dirty middle-aged men.” This is partly because, by the early '90s, the term had fallen into disuse and remained associated with its last major development. The rise of gag comics and kawaii in the late '70s and '80s practically buried the term.

I have heard Tatsumi had mixed feelings about the work he produced in the late '70s and '80s, but I find its super-pulpiness quite fun. Needing work, Tatsumi created a number of erotic manga. Perhaps the fact that these are largely comical (a feature of manga rather than gekiga in Tatsumi’s mind) was the artist’s way of making money without compromising the idea of gekiga. He also produced a number of bizarre serials, foremost amongst them being The Army of Hell (Jigoku no gundan, 1982-83) about a man raised by sewer rats who decides to rain hell on human civilization. As for the science fiction work he made in this period, Tatsumi pretty much disowned it in later years. However, one such title, Shoot the Sun (Taiyō o ute, early-mid '80s), about bioengineering designed for alleviating starvation in Africa being used to create mutant humans for world domination, would probably have an audience today. Sadly, since its initially serialization in Weekly Yomiuri, Shoot the Sun has never been reprinted and one has to go to the magazine department of the Tokyo Central Library to read it.

And then was another low period, lower even than the mid '60s. This era, as it immediately precedes the commencement of A Drifting Life and thus Tatsumi’s rise to global fame, is worth recounting despite its poverty of noteworthy work. After 1983, Tatsumi’s magazine serials become few and far between. Faced with unemployment, in 1984 he opened a used manga bookstore in Jinbochō named Don Comic. Comics work trickled in. He did layouts and penciling for Mizuki Shigeru for a year beginning in 1986. Shūeisha (publisher of Shōnen Jump) hired him to illustrate one book on international “travel troubles” (1989) and another on understanding criminal law (1994).

A Drifting Life started unglamorously in 1995 as a serial for the quarterly auction catalogue of Mandarake, the vintage manga and related collectibles megastore. The last chapter appeared in 2006, bringing to a close twelve years of work. But during the '90s, Tatsumi’s main work was illustrating the “Buddhist Comics” series from Suzuki Shuppan – which is interesting, because it means that in the years just before and while writing his own life story, Tatsumi was drawing those of the monks Bodhidharma, Kūkai, and Saichō, as well as introductions to shūgendō (mountain asceticism) and various deities from the Tibetan-Esoteric pantheon. The Don Comic store converted to mail order in 2002. A website still existed online in 2010, there for all to see how Tatsumi made a living before the Drawn & Quarterly books set him free. Looking back, the only hints of the future were the one French (1983), one Spanish (1984), and one American edition (1987) of his work circulating in small print-runs overseas.

A Drifting Life was collected and published as a two-volume set by Seirinkōgeisha in 2008, just as Tatsumi’s star was beginning to rise in the West. Since then, it has gone through multiple printings in Japan and North America. As mentioned before, Tatsumi won a prize at Angoulême in 2005, the Tezuka in 2009, and the Eisner in 2010 – with A Drifting Life itself recipient of the last two. It, along with a handful of Tatsumi’s short stories published by Drawn & Quarterly, inspired an animated film, Eric Khoo’s TATSUMI, which debuted at Cannes in May 2011. Ahead of the movie’s release in Japan, Seirinkōgeisha published a collection of the individual comics animated in Khoo’s movie. In late March 2011, the Japanese television station WOWWOW aired “The Godfather of Gekiga,” a celebratory documentary of the artist focusing on the latter '50s and the period when he, Matsumoto Masahiko, Saitō Takao, and others publishing with Osaka’s Hinomaru Bunko revolutionized comics-making in Japan.

Ironically, it is precisely this early period that is most obscure in Tatsumi’s career. The only book-length example readily available in Japanese or English is Black Blizzard, reissued by Seirinkōgeisha in 2010, and then soon after by D&Q. There’s also two stories in the facsimile reprint of Shadow and The Street from Shōgakukan Creative (2009), and a couple books (and not the most important ones) available as e-books. But that’s it. Unless some publisher takes the initiative to excavate some of the early kashihon work, what “gekiga” originally constituted in artistic terms (rather than what it became in discourse) will remain a mystery for all but an esoteric cabal of manga researchers and collectors.

Tatsumi was a hearty seventy-three when A Drifting Life was first issued in book form. Despite his age, he continued being productive. He published one book of new stories in 2009, Fallen Words (Gekiga yoriseki), which was issued in English translation by Drawn & Quarterly in 2012. He also published a prose autobiography, Gekiga Living (Gekiga kurashi, 2010), which repeats the coverage of A Drifting Life before extending into the '60s and up to the present. That same period was reportedly to be covered in the sequel to A Drifting Life that Tatsumi was working on at the time of his death. It is an immense loss to both fans and historians that this book will not be finished. Dug in deep as an artist, editor, and publisher for many decades, Tatsumi was not only a history-maker but also a living archive, and now he is gone. Happily a twenty-page excerpt of said sequel will appear in the forthcoming 25th Anniversary volume from Drawn & Quarterly. It is not known how much more was completed, but hopefully the remainder will be brought out soon in some format.

Let me close on a personal note.

I had the privilege of meeting Tatsumi twice. The first time was in Jinbochō at a quirky split-level café called Sabouru, which Tatsumi (and also Tezuka) frequented to relax and sketch stories and layouts. This meeting was thanks to the editor-scholar extraordinaire Asakawa Mitsuhiro. Amongst his many many credits, Asakawa was one of the founding editors of Ax and the person who approached Tatsumi to begin writing an autobiography for Mandarake Zenbu. My invitation to Sabouru was actually only an afterthought. I was piggybacking a meeting Asakawa had arranged for Sean Michael Wilson in celebration of the first Ax volume from Top Shelf (which included a late short story by Tatsumi). Asakawa’s idea was to turn the occasion into a casual roundtable on the present state of alternative manga in English translation, so he emailed me at the eleventh hour. But gaga with the opportunity to meet my object of research, I kept pestering Tatsumi with questions about the past, rather than keeping to the assigned topic. I think I am partly to blame for the fact that the conversation never got published.

The second time I met Tatsumi was at the after-party of a talk Tatsumi gave in 2011. This was part of a lecture series on kashihon manga at the Morishita Cultural Center (which houses a small Tagawa Suihō exhibition corner) in eastern Tokyo. That the room was filled with hardcore collectors, researchers, and a few senior comics industry people, totaling not more than fifty people, gives you a sense of how under-appreciated Tatsumi remained in Japan even after the public acclaim of A Drifting Life.

Tatsumi changed many people’s lives as cartoonists. He changed mine as a historian. Asakawa never fails to remind me, whenever the topic of Tatsumi comes up, how I first scoffed at his work. This was back when I first started seriously working on manga, in the early '00s. Through Seirikōgeisha, where he worked for many years, Asakawa had edited two collections of Tatsumi’s '60s and '70s work, titled The Great Discovery (Dai hakken, 2002) and The Great Excavation (Dai hakkutsu, 2003). He gave me a copy of each insisting that if I was going to write about Garo then I must know the roots of “alternative manga” in Tatsumi’s gekiga. I refused the idea outright, for the stupid reason that, as an art history student with a thin understanding of manga history, I could only see Garo in relationship to other visual media and literature. But Asakawa was right. Though I think Tatsumi’s kashihon era is no more “alternative” than say EC Comics, it is very clear to me now, after spending years reading kashihon manga, that what Tatsumi did in the '50s enabled what Tsuge Yoshiharu did in the late '50s and '60s, as well as what Hayashi Seiichi and Tsuge Tadao did in the '60s, as well as what Katsumata Susumu did in the '70s, to say nothing of the impact his ideas had on mainstream manga through figures like Saitō Takao, Satō Masaaki, and Arikawa Eiichi.

Tatsumi also changed me as a manga collector. For this I curse him, because it has made me poor. I can remember the moment very clearly. It was New Year’s 2012. Mandarake in Nakano was having its annual year-opening sale, where they invite their most loyal customers to have a first go at the gems freshly pulled from storage. My research on early kashihon gekiga had stalled, for the simple fact that I could not find the books that I knew existed – knew existed in many cases from reading about them in A Drifting Life. So there I was standing in the hallway upstairs at the Maniac Department (someone who is into old manga is a “maniac” rather than an “otaku”), more a curious anthropological observer to the obsessed buying that was about to take place than a participant, for at that time I still shied away from the expensive stuff. I snickered at one forty-year-old man who was crestfallen because someone else got first to that rare supplement of Terebi Magazine with the Kamen Rider cover.

But wait. What is that? There in the showcase I saw not one, not two, but THREE Tatsumi manga from that ESSENTIAL Hinomaru bunko era (1954-56). Was that fat guy in front of me eyeing them or something else? Hadn’t I seen that sweaty dude in front of him at a manga talk at Morishita? Suddenly I found myself inside a kashihon gekiga: bulging eyes, sweat on the brow, a close-up of the anxiety-causing object, and then NOOOOOO screaming (internally, like indigestion) when the terror becomes too much.

Many of Tatsumi’s early suspenses end happily, and so also did my Mandarake drama. When the crowd dissipated, the books were still there. But then a new chapter of horror commenced when I asked the price. I had never spent so much on something that didn’t have walls, wheels, or microchips. More collectors arrived and began milling about in front of the showcase. Tick tick. Tick tick. Must act fast. Will never see this book again. Have looked hard for The Man Who Laughs in the Darkness. Must have it. Will fit perfectly in essay I want to write about Hitchcock and gekiga. Someone else approaching. Will never find it again. Now or never. Now or never. This is crazy. Too much money. Okay, never. Wait. Think of all the research time I will save by buying it. Calculate money from TCJ for the essay. That’s silly. They don’t pay me squat. Forget it, never. No, wait, NOW! Hai, onegaishimasu!

And that was the beginning of the end for me. Because once you do it once, you realize how easy it is to do it again, and again. And so the next day I went back to buy the other two Tatsumis, which were even more expensive than the first one. And so on and so forth, for the past couple of years, and now I am so poor I can only afford to live in a Third World country. Finally, with the Matsumoto Masahiko project, I find myself getting back into that material and making use of all the “resources” I “invested” in at “institutions” like Mandarake. But still the guilt remains.

Someday, sensei, vengeance will be mine!