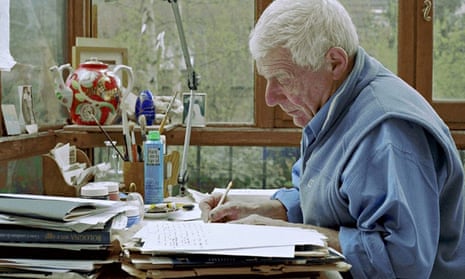

I have been writing for about 80 years. First letters then poems and speeches, later stories and articles and books, now notes. The activity of writing has been a vital one for me; it helps me to make sense and continue. Writing, however, is an off-shoot of something deeper and more general – our relationship with language as such. And the subject of these few notes is language.

Let’s begin by examining the activity of translating from one language to another. Most translations today are technological, whereas I’m referring to literary translations: the translation of texts that concern individual experience.

The conventional view of what this involves proposes that the translator or translators study the words on one page in one language and then render them into another language on another page. This involves a so-called word-for-word translation, and then an adaptation to respect and incorporate the linguistic tradition and rules of the second language, and finally another working-over to recreate the equivalent of the “voice” of the original text. Many – perhaps most – translations follow this procedure and the results are worthy, but second-rate.

Why? Because true translation is not a binary affair between two languages but a triangular affair. The third point of the triangle being what lay behind the words of the original text before it was written. True translation demands a return to the pre-verbal. One reads and rereads the words of the original text in order to penetrate through them to reach, to touch, the vision or experience that prompted them. One then gathers up what one has found there and takes this quivering almost wordless “thing” and places it behind the language it needs to be translated into. And now the principal task is to persuade the host language to take in and welcome the “thing” that is waiting to be articulated.

This practice reminds us that a language cannot be reduced to a dictionary or stock of words and phrases. Nor can it be reduced to a warehouse of the works written in it. A spoken language is a body, a living creature, whose physiognomy is verbal and whose visceral functions are linguistic. And this creature’s home is the inarticulate as well as the articulate.

Consider the term “mother tongue”. In Russian it is rodnoy-yazik, which means “nearest” or “dearest tongue”. At a pinch one could call it “darling tongue”. Mother tongue is one’s first language, first heard as an infant.

And within one mother tongue are all mother tongues. Or to put it another way – every mother tongue is universal. Noam Chomsky has brilliantly demonstrated that all languages – not only verbal ones – have certain structures and procedures in common. And so a mother tongue is related to (rhymes with?) non-verbal languages – such as the languages of signs, of behaviour, of spatial accommodation. When I’m drawing, I try to unravel and transcribe a text of appearances, which already has, I know, its indescribable but assured place in my mother tongue.

Words, terms, phrases can be separated from the creature of their language and used as mere labels. They then become inert and empty. The repetitive use of acronyms is a simple example of this. Most mainstream political discourse today is composed of words that, separated from any creature of language, are inert. And such dead “word-mongering” wipes out memory and breeds a ruthless complacency.

What has prompted me to write over the years is the hunch that something needs to be told, and that if I don’t try to tell it, it risks not being told. I picture myself as a stop-gap man rather than a consequential, professional writer.

After I’ve written a few lines I let the words slip back into the creature of their language. And there, they are instantly recognised and greeted by a host of other words, with whom they have an affinity of meaning, or of opposition, or of metaphor or alliteration or rhythm. I listen to their confabulation. Together they are contesting the use to which I put the words I chose. They are questioning the roles I allotted them.

So I modify the lines, change a word or two, and submit them again. Another confabulation begins. And it goes on like this until there is a low murmur of provisional consent. Then I proceed to the next paragraph.

Another confabulation begins ...

Others can place me as they like as a writer. For myself, I’m the son of a bitch – and you can guess who the bitch is, no?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion