Urbanization provides the countries of South Asia with the opportunity to transform their economies to join the ranks of richer nations. But to reap the benefits of urbanization, nations must address the challenges it poses. Growing urban populations put pressure on a city’s infrastructure; they increase the demand for basic services, land and housing, and they add stress to the environment.

Of all these congestion forces, one of the most serious for health and human welfare is ambient air pollution from vehicle emissions and the burning of fossil fuels by industry and households, according to the World Bank report, “Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability.”

Particularly harmful are high concentrations of fine particulate matter, especially that of 2.5 microns or less in diameter (PM2.5). They can penetrate deep into the lungs, increasing the likelihood of asthma, lung cancer, severe respiratory illness, and heart disease.

Data released by the World Health Organization (WHO) in May 2014 shows Delhi to have the most polluted air of any city in the world, with an annual mean concentration of PM2.5 of 152.6 μg/m3 . That is more than 15 times greater than the WHO’s guideline value and high enough to make Beijing’s air—known for its bad quality—look comparatively clean.

But Delhi is far from unique among South Asia’s cities.

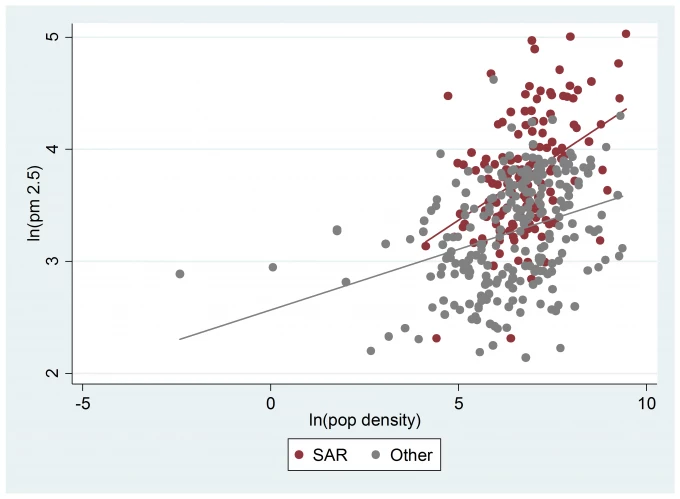

Controlling for factors like climate (levels and variability of rainfall and temperature) and geography (such as distance to the coast), analysis of the data shows that, for developing-country cities globally, annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 are positively and significantly correlated with both city size and population density within a 20-kilometer radius of the city center. Although these relationships are expected, they are stronger in South Asian (SAR) cities for population density than in other developing-country cities (see figure below). In developing-country cities outside South Asia, a doubling of population density is associated with a 24.2 percent increase in PM2.5, but in South Asian cities the increase is 34.8 percent.

Relationship between annual mean concentration of PM2.5 and city population density for 381 developing-country cities

Relationship between annual mean concentration of PM2.5 and city population density for 381 developing-country cities

So, what accounts for this uniquely strong impact in South Asian cities?

More research is needed, but it seems plausible that the answer lies in the relationship between a city’s population density, the number and spatial configuration of potential pollution sources within or near a city, and the volume of pollution emitted by each source. For example, given failures in planning, one can speculate that an increase in population density is associated with a greater probability of traffic gridlock in South Asian versus non–South Asian cities, contributing to a higher relative increase in air pollution. It’s also possible that, for South Asian cities, a given increase in population density could be associated with a proportionally larger increase in forms of economic activity that rely on dirty forms of energy. For example, small- and medium-sized enterprises all typically rely on dirty energy forms in developing countries.

Tackling the problem requires policy responses—and quickly.

Indian cities have been known to battle air pollution successfully in some places and at particular times. Despite these measures, however, most cities are losing the war.

A new wave of pollution control initiatives is needed. These measures will have to range from further improvements in fuel quality and vehicle technology to greater access to public transport and changes in patterns of urban development to reduce the need for transport, as well as switching industries and households to cleaner fuels. Indian cities will also need to improve air quality monitoring to get a better handle on the extent of the problem and to invest in source apportionment studies to better understand pollution sources.

To read the report, go to: www.worldbank.org/southasiacities.

Join the Conversation