This is the fourth in our series of posts by students on the job market this year.

Institutions are widely believed to be important drivers of development. Recently, economists have begun using detailed micro data to study how historical institutions can shape development outcomes decades or even centuries down the line. But for anyone interested in development, a key question is what causes institutions to change over time. Here, the evidence is more scant. In my job market paper, my co-author Erik Prawitz and I ask if large-scale emigration can be a mechanism leading to political change in origin countries.

We look at the mass emigration of Swedes to the United States starting in the mid 1800s, and compare political outcomes across locations that experienced more and less emigration over the period 1867-1920. Although Sweden is known to be a rich and egalitarian country today, the opposite was true in the 19th century. In the span of sixty years, a quarter to the population seized the opportunity to make a new life for themselves overseas. The question we ask is what political effects this had in the country that migrants left behind. To do so we use detailed data on the Swedish labor movement, which emerged in this period and became a key player in reforming Swedish policy and political institutions.

It is not clear, however, if the labor movement grew because of or despite Sweden’s mass emigration. In his seminal book “Exit, Voice and Loyalty” (1970), Albert O. Hirschman hypothesized that emigrants would be those who were most opposed to the current regime, and hence that out-migration would lower activism. On the other hand, since labor activism was highly risky for the individual - one could be fired or blacklisted for being a union member - having the outside option of leaving the country could potentially promote activism.

Identification strategy: frost shocks and path dependence

To estimate the causal effect of emigration on labor organization, we make use of two interesting features of the Swedish emigration. First, it is well known that migration patterns tend to be very path dependent. In other words, people and places with more migration experience tend to migrate more in the future. Sweden was no exception, not least because emigrants would send home pre-paid tickets for family members to join them overseas. In fact, it is estimated that 40 to 50 percent of all migrants traveled on pre-paid tickets. The neat feature of path dependence for us is that if we can find a way to explain why initial emigration occurred, we can hope to have an instrumental variable to explain variation in total emigration in the whole period.

This is where the second feature of the Swedish emigration comes in. We use the fact that the initial wave of Swedish mass migration started in the late 1860s due to a series of particularly poor harvests, caused by cold weather. Using daily temperature data from the period, we therefore define random growing-season frost shocks between 1864 and 1867 to proxy for crop failures. We then define an instrument which only captures variation in early migration push factors: the interaction between frost shocks 1864-1867 and the shortest distance from a municipality to one of the two major emigration ports. Using only this interaction term as our instrument allows us to control for both port distance and frost shocks themselves, which avoids picking up any confounding direct effects of severe economic shocks on political outcomes. The geographical spread of frost shocks and the location of emigration ports are displayed in Figure 1.

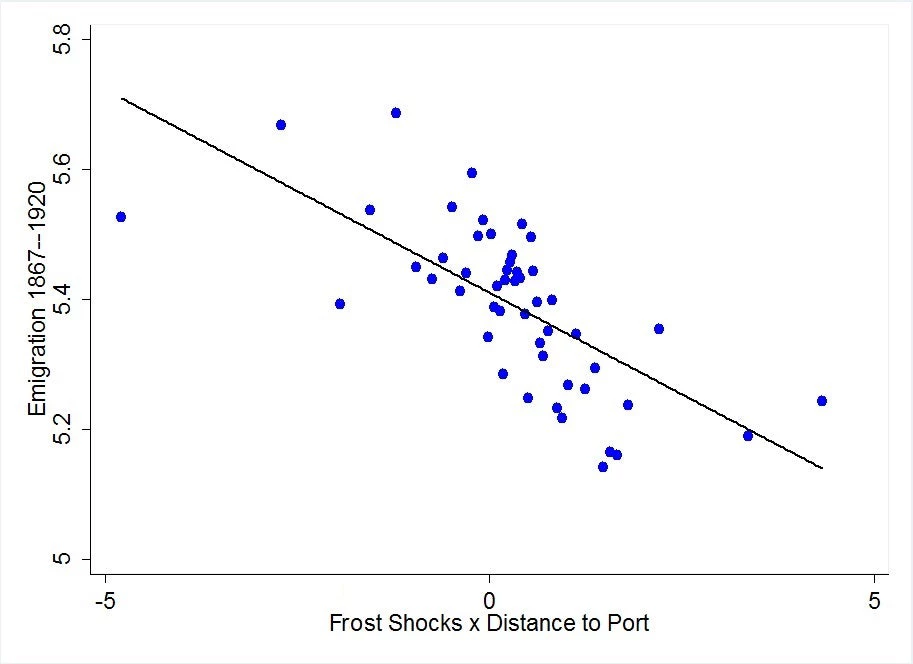

Digitized data from local priests as well as ship passenger lists are used to quantify total emigration across Sweden’s 2400 historical municipalities. In line with our expectations, stronger push factors prior to the first wave of mass emigration predict higher total emigration in the whole 1867-1920 period. Figure 2 displays this relationship graphically, where higher values on the x-axis indicate weaker push factors. As a verification that shocks are not simply picking up constant municipal factors related to climate and port distance, we show that frost shocks occurring in the non-growing seasons 1864-1867 have no effect on emigration or any second stage outcomes.

Results: Emigration and political change

Our main result is that emigration significantly increases local labor movement membership, which we define as membership in labor unions and the Social Democratic Party. Our estimates indicate that a doubling of emigration would move a municipality from the mean to the 90th percentile of labor organization rates.

These results hence suggest that the mass emigration of Swedes empowered remaining citizens to organize collectively against economic elites in a time when such activism could be very risky. Using census data, we can also verify that these impacts remain if we condition on the local employment structure. That is, the effect is not simply due to emigrants coming from less unionized sectors. Instead, we believe that this indicates a real increase in the bargaining power of citizens. As mentioned above, one reason could be that the emigration option acted as an insurance against repression from employers and enabled a higher degree of labor activism. Another, complementary hypothesis is that employers became more susceptible to workers’ demands when worker mobility increased. As a result, the benefits of organizing for collective action may have gone up.

To further probe the effects on the labor movement, we use some additional indicators. We find that participation in a 1909 general strike, involving 300,000 workers, was higher in locations with more emigration. Thus membership in the labor organizations also mobilized workers to collective action. In line with the labor movement’s close ties to the political left, we also find that voting for left-wing parties increases in national elections 1911-1921. This effect persists in contemporary elections as well, albeit diminished by about half.

In conclusion, we find broad evidence of emigration having bolstered participation in the labor movement, mobilization of protests and corresponding left-wing party preferences. Given the marked increase in citizens’ demand for political change, a natural question is if this is reflected in local government actions. Two different indicators suggest that this was the case. First, we find that municipal welfare expenditures per capita are significantly higher in municipalities with more emigration. Interestingly, this is true even before the introduction of democracy, when voting power was heavily biased in favor of economic elites. The observed increase in expenditures is therefore unlikely to have been caused by changes in the preferences of ordinary citizens. Rather, it is consistent with concessions being made by elites in favor of citizens. Lastly, we find that high-emigration municipalities are more likely to adopt representative rather than direct democracy. Recent evidence has shown that direct democracies had lower levels of redistribution and were likely more prone to elite capture.

Conclusion

Overall, mass emigration brought positive effects on citizens' bargaining power and resulted in a more inclusive political equilibrium during a time when Sweden was still undemocratic. Migration arguably played a role in the country's transition to a full democracy in the early 20th century. On a speculative note, the fact that many countries experienced high rates of US emigration in this period raises the possibility that the free immigration policy maintained by the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries had significant unintended consequences for political development in the rest of the world.

Mounir Karadja is a PhD student at the Institute for International Economic Studies (IIES), Stockholm University. His website can be found here.

Join the Conversation