Every day more and more people in the world have access to financial services. In the minds of many, that poses an important risk. People need financial education, particularly in the form of information, to prevent them from making dangerous financial mistakes. They need to be aware of fees they pay, the interest rate charged by their credit cards, and important clauses in the contracts they sign.

The funny thing is, not even people we consider financially savvy know those things. I put these kinds of questions to 30 Mexican economists, all PhDs working in the financial sector or in academia. 38% did not know the APR of their credit cards. 66% did not know approximately how much they paid last year in fees to retirement fund managers. 72% claimed they do not usually read the fine print in bank contracts.

It would be extremely hard to justify any policy that would give financial education to those PhDs. More importantly, nobody would seriously believe they are at any real risk. We might implicitly agree that they know both what a financially-healthy lifestyle is, and how they can achieve it through general rules of thumb. Additionally, someone who earns a PhD is likely analytic, self-restrained, and not-impulsive. Those traits are helpful for staying out of trouble, including the financial type.

Any policy to promote “financial health” would likely benefit from drawing parallels with the promotion of a healthy lifestyle. Knowing the trans-fat contents of different foods or the calories burnt when using different settings of the elliptical at the gym does not equal a healthy lifestyle. Knowledge alone is not enough. Conversely, the lack of such detailed information does not necessarily imply a health disaster. It is true that a healthy lifestyle requires general knowledge to distinguish “good” practices from “bad” practices, but it also requires sticking to the good practices. That in turn demands willpower, patience and perseverance. Put that way, it is not surprising that personality traits measured in childhood are found to be determinants of health in adulthood.

The relevance of personality to lifetime outcomes extends to other areas beyond health. Financial culture is one of them. Several studies in different countries with subjects of different ages have found some association between personality and financial culture.

A study of my own, recently published in the International Handbook of Financial Literacy, contributes to that literature. It uses survey data for a nationally representative sample of 3,200 Mexican youth, ages 15 to 29. In the study, personality is measured with the “Big Five” and financial culture is measured with 41 items—more than what is typically used in other personality-related studies. Those 41 items are analyzed in two different ways: grouped into eight separate “aspects” of financial culture, and summarized in a single index of financial culture using principal components.

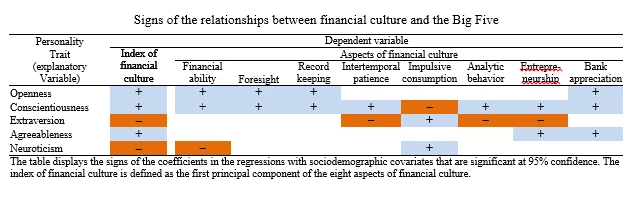

The table below summarizes the main results of the study. The columns correspond to the eight aspects of financial culture and the principal components index. The rows correspond to the Big Five and the measure of cognitive skills. The interior of the table shows the signs of the partial correlation coefficients between the measures of financial culture and the Big Five (also known by the acronym OCEAN) that are significant at 95% confidence. Definitions of each scale used and the methods employed can be found in the study.

In sum, openness, conscientiousness and agreeableness are positively related to financial culture. Extraversion and neuroticism are negatively related to financial culture.

To put the results in more mundane terms, suppose there are two youths, A and B. Suppose also that we know their scores in the Big Five. Youth A has low scores in openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, and high scores in extraversion and neuroticism. Youth B is in the opposite situation: she scores high in openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, and scores low in extraversion and neuroticism. If you had to choose either A or B to participate in a financial education program, you should definitely pick A. After all, we expect A’s financial culture to be well below average—B’s is expected to be well above average.

Here is another scenario where the results above would be relevant. Suppose an organization has a website offering financial-education tools for youths in a specific target population—say public high schools in a school district. Suppose the organization learns that students using the website exceed the district’s average in openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, but are below average in extraversion and neuroticism. In light of the results above, the organization should reckon whether their strategy is reaching those in greater need of financial education among its target population.

The successful take-up of many financial-education programs implicitly requires self-discipline, commitment, perseverance, and more. Those programs may be excluding by design—although unintendedly—people who lack such traits. Ironically, those might be precisely the individuals who could benefit the most from learning how to make better financial decisions. This is particularly compelling because financial-education programs seek to increase financial culture among those who have the least—they are not targeting the top or the middle of the distribution of financial culture.

Although no concrete recommendations stem from the results above, they suggest a path ahead. First, more research is needed to understand personality as a determinant of financial lifestyles. Second, whenever possible, impact evaluations of financial-education programs should include measurements of personality traits. The combination of measurements of personality traits with knowledge about the role they play would help improve programs and increase their effectiveness.

Join the Conversation