The Socialist Case Against Bernie

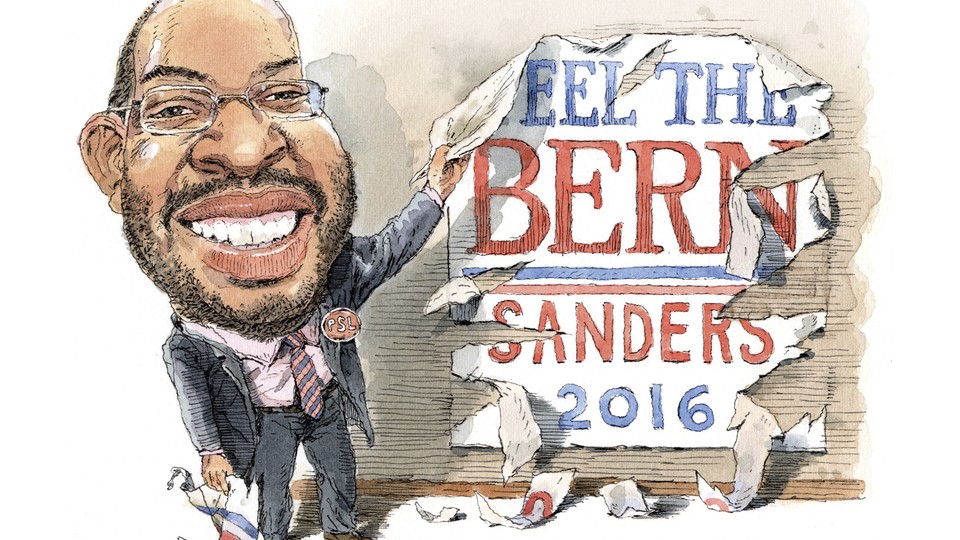

Eugene Puryear explains why Sanders isn’t revolutionary enough.

I had many questions for Eugene Puryear, the real-life socialist politician seated across the table from me. Did he really want to nationalize the Fortune 500? Why wasn’t he on board with Bernie Sanders? And why had he suggested we meet at a Washington, D.C., fast-casual chain restaurant—the kind of place that practically screams “post-industrial capitalist exploitation”?

At the last question, Puryear, an affable 30-year-old with a round face and scruffy beard, grinned sheepishly. Having just finished hosting his weekly radio show on the left-wing Pacifica network, Puryear was digging into a plate of Mediterranean chicken. He tried, he said, not to participate in capitalism’s worst excesses; he was considering downloading an iPhone app that alerted users to the latest social-justice boycotts. But the larger problem was a systemic one: “If you look at the global capitalist system, working people are being treated terribly to produce every commodity, from the clothes we wear to the furniture we use,” he said. In his view, capitalism is exploitation, so the only way to stop exploitation is to overthrow capitalism—as he proposes to do.

Sanders, the self-described democratic socialist vying for the Democratic presidential nomination, surprised the party establishment and the commentariat this year by becoming the last candidate standing against Hillary Clinton. I wanted to know how the socialist movement felt about his candidacy. So I sought out Puryear, who is running for vice president on the ticket of the Party for Socialism and Liberation, a socialist organization that expects to be on about a dozen states’ ballots this November. The ticket is headed by Gloria La Riva, a San Francisco–based labor and antiwar activist who has been agitating for social justice since the 1970s.

Until recently, socialist was effectively a slur in political circles. (In 2011, a formal complaint was lodged against a Republican congressman who referred to Democrats using the term, and it was struck from the Congressional Record.) But this year, Sanders, with his youth movement and his calls for “political revolution,” reintroduced the label to polite company. At enormous rallies across the country, his fans told journalists they were proud to call themselves socialists. For a political movement long confined to the fringes of American discourse, Sanders would seem to have done an enormous service.

But as it happens, the real socialists—the ones toiling, lonely, in the trenches; the ones who never felt a need to temper their philosophy with a mitigating adjective like democratic, as Sanders does—are strikingly ungrateful. Puryear’s party, the PSL, issued a statement last August, when Sanders began to gain traction, tartly rejecting his campaign. “His program is not socialist,” it noted.

He does not call for nationalizing the corporations and banks, without which the reorganization of the economy to meet people’s needs rather than maximizing the profits of capitalist investors could not take place … He is clearly seeking to reform the existing capitalist system.

The crowds at Sanders’s events, the PSL contended, showed popular hunger for a far-left platform. But Sanders wasn’t really providing one—he was, they implied, guilty of a bait and switch. Some in the socialist blogosphere (like all fringe political movements, socialism has a lively and disputatious Internet presence) have gone further. Socialist Action, a Trotskyist organization, accused Sanders of a pernicious “lesser-evil politics” designed to hoodwink workers into supporting the corrupt Democrats.

Puryear isn’t so antagonistic. Some effects of Sanders’s rise are, he told me, worth applauding. “He has revealed that there are millions of people who not only are progressive on the issues, but in a more holistic way are willing to refer to themselves as socialist,” he said. “It’s exciting to know that young people haven’t lost all hope.” And yet, when it comes to substance, Puryear considers Sanders’s policy ideas inadequate. “Our economy as it’s currently constructed cannot possibly provide enough decent employment for the number of people being born every single day,” Puryear said. The solution, in his view, is to take the aggregate product of society’s labor and, rather than let the market allocate it mostly to the upper classes, divide it to meet everybody’s needs.

Puryear, who grew up in Charlottesville, Virginia, a couple of hours south of D.C., has always been political. “The feeling that, if you think something’s wrong, you’d better do something about it is strong in my family,” he told me. According to family lore, a maternal ancestor was a Reconstruction legislator; a grandfather was active in the Communist Party–affiliated Popular Front; his father was a civil-rights activist. Puryear protested the Iraq War when he was 16 and plunged into activism at Howard University, getting involved with the Latin American–solidarity and pro-Palestinian movements.

Along the way, Puryear came to think of himself as a socialist, and while he was vaguely aware that some people might consider his identification outré, in his circles it was pretty acceptable. This was not entirely because of the company he kept; it was also a reflection of his generation. Millennials, he told me, don’t have the same hang-ups about socialism that their parents once did.

Surveys back up Puryear’s impression. A January poll by YouGov found that 43 percent of Americans ages 18 to 29 have a favorable view of socialism—nearly double the proportion of those 65 and older. That may be because they didn’t grow up in the shadow of the Cold War. But having come of age in the time of financial crashes and Occupy Wall Street, young people may also be more skeptical of free markets. In the same poll, just 32 percent of young people had a favorable view of capitalism, versus 63 percent of seniors.

Sanders himself never sought to identify as a socialist: Only when his enemies started accusing him of being one did he, in characteristically pugnacious fashion, reappropriate the insult as a badge of pride. Some critics have pointed out that it would be more accurate to call him a social democrat, rather than a democratic socialist. After all, Sanders has said he defines democratic socialism as something akin to the systems in Denmark or Finland—countries with high taxes and a capacious welfare state, but relatively free markets.

“The ideology of the Scandinavian governments is really just a more fair capitalist society,” Puryear told me. True socialism as Marx and Engels envisioned it, by contrast, was intended as a way station on the road to full-fledged communism. “We refer to ourselves as socialists because what we’re trying to promote is the move from capitalism to socialism,” he said. But the ultimate goal is not Finland. It is a fully classless society in which the state has withered away to nothing.

When I asked Puryear about communism’s failures around the globe, he became defensive. The past century’s worth of socialist experiments were limited, he said, and undermined by U.S. meddling. Whatever their flaws, regimes like Venezuela’s don’t, in his view, get the credit they deserve for lifting people out of poverty. (Puryear has been to Venezuela twice, most recently in 2013.) And America, he insisted, is better positioned to implement socialism by virtue of its wealth. Puryear furthermore took issue with my question’s premise. “Capitalism is also responsible for some of the worst crimes in history,” he contended, mentioning imperialism, world war, and the transatlantic slave trade. “Why isn’t that considered discrediting?”

American socialists have never gotten far. Their heyday, insofar as they had one, was in the early 20th century, under the leadership of Eugene V. Debs—whose likeness hangs in Sanders’s Senate office. Debs’s fourth presidential run, in 1912, earned the Socialist Party of America 6 percent of the vote, still the high-water mark for a socialist candidacy; his successor, Norman Thomas, never came close to such popularity in his six presidential runs, and the party fell apart under the scrutiny of the Red Scare. In the 1970s, a few successor parties emerged, among them Socialist Party USA, whose 1976 nominee, the socialist former Milwaukee mayor, Frank Zeidler, got just over 6,000 votes. (While that party today claims to adhere to democratic socialism, it, too, finds Sanders insufficient: In the view of Mimi Soltysik, its 2016 nominee, Sanders’s rhetoric about the middle class is “bullshit.”)

In 2012, the PSL was on the most state ballots—13—of any socialist party, but received barely 9,000 votes. This year, the party’s 10-point platform calls for jailing Wall Street tycoons and confiscating their assets, providing “full rights for all immigrants,” shutting overseas military bases, establishing a constitutional right to “a decent paying job,” and ending fossil-fuel production. It overlaps with Sanders’s agenda in some areas, such as its call for free public health care, free college education, and a dramatically increased minimum wage. (Sanders favors $15 an hour, while the PSL advocates $20.)

Unlike major-party nominees, the PSL’s presidential and vice-presidential candidates don’t spend their time running around the country to town halls and rallies. Rather, Puryear mostly addresses student groups and participates in voter forums put on by civic groups that feature minor-party candidates alongside the major parties’. (The Staten Island NAACP is one perennial host.) He also seeks out mass events like concerts and sporting events, using them as opportunities to shake hands and distribute fliers.

When he’s not campaigning for vice president, Puryear is essentially a full-time activist. After graduating from college, he held odd jobs for a time—working in a warehouse, selling ice cream—but last year he cobbled together funding to form an organization called Justice First, which is devoted to affordable housing and workers’ rights. He’s also active in the Black Lives Matter movement and in local politics (he ran for the D.C. city council in 2014, coming in sixth out of 15 candidates).

After our lunch, I followed Puryear around town to meetings with fellow housing-rights activists. While we walked, he drew a connection between his party’s national platform and his ground-level work against gentrification. “Every city in the country has a housing crisis,” he told me, as we passed a shiny new high-end liquor store and a boarded-up bodega. The people who need homes aren’t rich enough to create demand, so developers keep making more high-end units. It was, he said, a textbook example of capitalism’s failure to provide for people’s needs.

Puryear is under no illusion that he’ll be moving into the Naval Observatory next year. At 30, he is not constitutionally eligible to serve as veep—his very presence on the PSL ticket is, in part, a protest against an age requirement he views as unfair. If his party manages to get on the ballot in the same states it did in 2012, it will be competing for just 146 electoral votes, far short of the 270 needed to win. “The point is to make these points,” Puryear told me.

And yet he believes 2016 could be a watershed year for socialists, thanks in part to Sanders. If, as seems likely as of this writing, Sanders falls short of the nomination, Puryear expects to see a large bloc of newly engaged leftist voters seeking a far-left electoral alternative to Hillary Clinton. He hopes they will discover the PSL. “We will make explicit appeals to [Sanders’s] supporters to back our socialist ticket over Secretary Clinton, who we feel is much further from their views than ours,” he said. Which is to say that Bernie Sanders could, in losing, score a win for American socialism.