-

The Elizabeth line platforms are massive. This photo wasn't even taken from the end of the platform!Sebastian Anthony

-

Part of the tunnel-boring machine "Elizabeth" is lifted down a main Crossrail access hole.

-

The twin-bore Crossrail tunnels are rather large.

-

The main building hole at the Hanover Square site.Sebastian Anthony

-

Walking up and down the stairs all day probably gets old quite fast.Sebastian Anthony

-

Before I was allowed down into the building site, I had to be shown what to do in case of emergency. Basically, "run away from the smoke if you can."Sebastian Anthony

-

Me in a lift. Obviously I wasn't going to take the stairs...Sebastian Anthony

-

This building site will become the Hanover Square ticket hall for the Bond Street Elizabeth line station. My office is the white building in the middle on the left. (My window overlooks the building site, which is why I was interested in Crossrail in the first place.)Sebastian Anthony

-

When I looked around the site, the Crossrail engineers were just about to hand over to another contractor, to lay down the track.Sebastian Anthony

-

Just some random tunnel, with a big ventilation tube running overhead.Sebastian Anthony

-

A barrier is being erected between the platform and the track, so that the track contractors can do their own thing. The platform screen doors will hang from the metal strip across the top-centre of the image.Sebastian Anthony

-

And here's what it looks like with the temporary platform-track divide erected.Sebastian Anthony

-

A big fan used for ventilation deep underground.Sebastian Anthony

-

Me, standing in a connecting tunnel.Sebastian Anthony

-

Just some access tunnel.Sebastian Anthony

-

Looking from the base of the ticket hall into the platform/train area. Huge.Sebastian Anthony

-

Looking down the giant access hole.Sebastian Anthony

-

A big ol' ventilation pump.Sebastian Anthony

-

A better view of my office building - the white building in the middle.Sebastian Anthony

-

Hundreds of tons of rebar, for the reinforced concrete structure of the ticket hall.Sebastian Anthony

-

For safety, there's a master list of everything that's going on that day on the site.Sebastian Anthony

-

Security is pretty stringent at the site.Sebastian Anthony

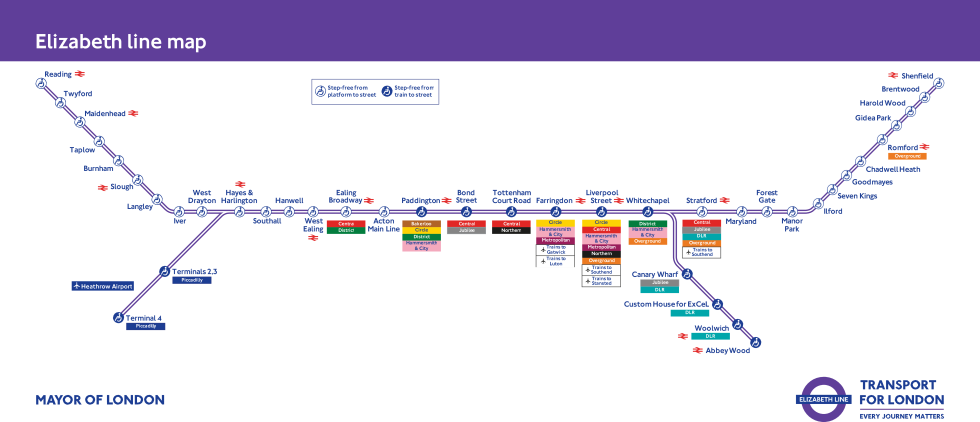

I'll let you in on a secret: I love big things. Big holes, big houses, big bridges, big cars. I suspect it has something to do with being very large myself. After spending most of my formative years living in old, low-ceilinged British houses, and developing a hunchback, I now find expansive spaces rather comforting. Which is why I recently paid a visit to the new Elizabeth line (née Crossrail) tunnels near Bond Street, London.

It's funny. If you've ever been on the London Underground, I doubt you'd ever describe it with words like "spacious" or "airy." More like "claustrophobic" and "ooh, look at that big rat!"

As the elevator juddered its way down the giant access hole at the new Bond Street station on London's Hanover Square, though, the only word that came to mind was "whoa." The Elizabeth line ticket halls, walkways, and train tunnels are really quite big.

Eight tunnel boring machines (TBMs), each about 100 metres long and weighing roughly 1,000 tonnes, worked around the clock for three years, with excavation completed at the end of 2015. Because the TBMs are so large and unwieldy, two of them—named Phyllis and Ada—were left buried in the ground near the new Farringdon tunnels. (I like to think that they were pointed at the centre of the Earth with a brick on the pedal... and they'll get there eventually.)

As you can see from the photos at the top of the story, the Crossrail train tunnels are a lot larger than those on any of the other Underground lines. The TBMs dug out raw tunnels that were about seven metres in diameter, but after numerous layers of reinforcement, and over-engineering and concrete cladding, the final internal diameter of the tunnels is 6.2m (20ft 4in)—the Victoria line, by comparison, has a diameter of just 3.81m (12ft 6in).

Another thing to note is the length of the platforms. At 250 metres (820ft), the Elizabeth line platforms are more than twice the length of current Underground platforms, which range between 122 metres (400ft) and 107m (350ft). The first trains will be 200 metres (660ft) long, but they can be extended to 240m (790ft) in the future if passenger demand increases. Because the platforms are so long, and the capacity of the trains so great, most Elizabeth line stations will have two large ticket halls that are spaced far apart. The two ticket halls for the Bond Street station, for example, are on Davies Street and Hanover Square—about 500 metres (1,640ft) away from each other.

I didn't learn much about the external construction of the Elizabeth line, but a Crossrail site manager did tell me one interesting anecdote. Slip forming (continuously poured concrete) is being used to build some of the taller ticket hall structures. The process is noisy, though, which means that in residential areas it can only be done during work hours. To speed up the process, Crossrail temporarily relocated some people who live near the ticket hall building sites to hotels, so that construction could be carried out around the clock.

reader comments

97