Three months after his heart bypass surgery at Greenville Memorial Hospital in South Carolina, 74-year-old Henry Weinacker found himself back in a hospital exam room with a bad fever. He'd been recovering steadily enough until then, his wife Lori thought. He kept saying his chest hurt, but she figured that was to be expected given that the operation had involved cracking his sternum.

It wasn't until nurses checked his surgical wound that Lori realized something was terribly wrong: The wound had burst open and was oozing pus, she said.

Tests revealed that Henry was infected with non-tuberculosis mycobacteria (NTM), a microbe that's harmless in healthy people but can be deadly in those with weakened immune systems. NTM is common in soil and water; but it's so rarely found in hospitals that one nurse told Lori she had never seen it in a chest wound before.

The news got worse from there: Doctors said Henry was too sick to withstand the treatment for NTM (several powerful drugs taken multiple times each day for six months or longer), and that not much else could be done for him. "We had to put him on hospice," she told Consumer Reports.

He died on June 22, 2014, three weeks after the infection was discovered. In the months that followed, officials at Greenville Memorial confirmed that 14 additional patients had been diagnosed with the same rare infection and that three others had also died.

An investigation conducted by the hospital and the South Carolina Public Health Department traced the offending bacteria to a piece of medical equipment well-known among surgeons but one most patients have never heard of: a heater-cooler device, or HCD.

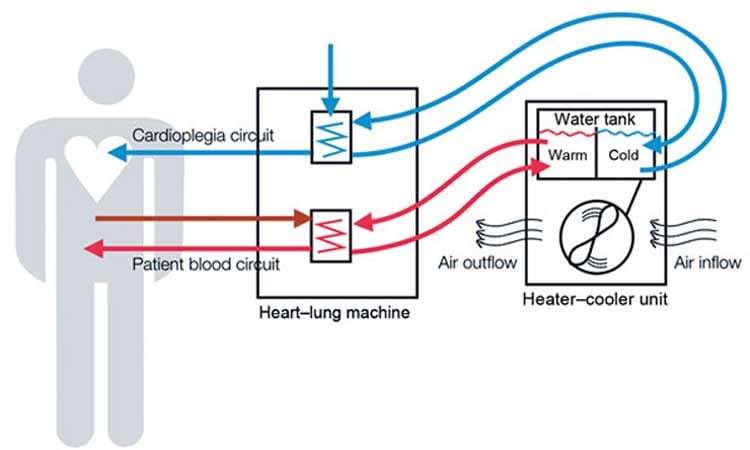

Heater-coolers are essential surgical devices that regulate a patient's body temperature during surgery; they're used in hundreds of thousands of surgeries each year, including heart bypass, heart-valve replacement, and other heart and lung operations. But owing to a basic design flaw, the machines can harbor—and then spray—deadly bacteria through their exhaust vents, across operating rooms, and into patients' open cavities.

The investigation at Greenville stopped short of saying that its heater-cooler devices were responsible for the outbreak of NTM infections, in part because the bacteria was found in other places throughout the hospital.

But attorneys for the victims say that the link is clear. "Yes, the bacteria is a common environmental contaminant," says Blake Smith, the lawyer who settled Lori Weinacker's wrongful death suit against Greenville Memorial Hospital in 2015. "But only the heater-cooler device is capable of aerosolizing that bacteria and spraying it directly into the chest cavity during surgery."

In the two years since Henry's death, that argument has been bolstered by a string of similar incidents (in Iowa, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere) and by an acknowledgement from the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that heater-cooler devices pose a small but potentially serious risk to heart surgery and other patients. From Jan. 1, 2010, to Feb. 29, 2016, the FDA received 180 incident reports related to heater-cooler devices around the world. The reports include 16 U.S. hospitals across 10 states, where at least 45 patients were infected and at least nine died.

So far, the vast majority of those incidents have involved a specific brand of heater-cooler: the Stöckert 3T, manufactured by the European company LivaNova, formerly known as Sorin. But at least three other companies' devices have also been linked to bacterial contamination worldwide, and both the FDA and CDC have acknowledged that the concern goes beyond any one brand.

"A wet machine with a big fan can result in these organisms," says Michael Bell, M.D., deputy director of the CDC's Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. "We need a better way of managing machines like this or a better design that doesn't have that problem."

In the meantime, hospitals are scrambling to manage a problem that pits an essential surgical device against a deadly bacterial infection, federal agencies are struggling to raise awareness of the issue, and experts are divided over when—or even whether—patients should be notified of the newly discovered risk.

Catherine Chang, M.D., chief medical officer for Greenville Memorial Hospital, said her facility stopped using the Stöckert 3T device in June 2014 and has adopted a "wide range" of additional precautions, going "above and beyond CDC recommendations," to better protect patients.

Since 2015, the FDA and CDC have each issued advisories urging hospitals to take steps to prevent their heater-coolers from spraying bacteria across the operating room, and to be on the lookout for NTM infections in heart-surgery patients who have had valve replacement or bypass surgery. So far, the CDC says, those warnings have yet to catch on among doctors and hospitals. "Despite 12 months of communication on this issue, awareness remains much lower than it should be," says Joseph Perz, Dr.P.H., an infection control expert with the CDC.

In October, the agency issued a third, more urgent advisory calling on hospitals that use the Stöckert 3T device to develop a system for alerting patients and healthcare providers in the event of an outbreak. Critics say that advice doesn't go far enough, in part because it should extend to all hospitals using any brand of heater-cooler.

A Difficult Diagnosis

Heater-cooler devices, which look like freestanding portable air conditioners and have been used for heart surgery since the 1960s, contain tanks of water that circulate through narrow tubes. The machines were considered safe because although the water isn't sterile, it also doesn't come into direct contact with the patient.

But in 2015, researchers discovered that bacteria from the water can seep into other parts of the machine and multiply there, and that if that bacteria reaches the exhaust fan, it can be sprayed through the air during surgery.

So far, the numbers suggest that the risk of any given HCD being contaminated or infecting patients is very small. But NTM infection is inherently difficult to diagnose, and several experts have said that the confirmed cases probably represent just a fraction of the actual infections.

"We know there are infections out there that are going undiagnosed," says Michael Edmond, M.D., a hospital epidemiologist at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City, where heater-cooler contamination has been detected.

Part of the problem is the bacteria itself. Some strains of NTM grow so slowly that it can take as long as four years for symptoms to emerge, making it unlikely that a doctor will link those symptoms to the surgery.

What's more, the infection is so rare, and the tests used to diagnose it so cumbersome, that most doctors never bother to look for it in the first place.

A Growing Problem

Since the Greenville outbreak, several more NTM-infection clusters have been potentially linked to HCDs. In Pennsylvania, two hospitals have publicly reported NTM outbreaks that could be linked to their heater-cooler devices, and at least 14 probable patient infections have been identified. In Iowa, two hospitals reported a total of three possible heater-cooler-related NTM infections.

And the Mayo Clinic—which has major campuses in Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota—has confirmed one NTM infection in a heart-surgery patient and found that several of its heater-coolers were contaminated with the bacteria. The hospital is in the process of sending out 17,000 letters, warning every patient who has been exposed to the contaminated devices.

At the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, five patients were sickened and two of them died after being infected with another type of bacteria, legionella. Like NTM, legionella is common in the environment but rare and potentially deadly in hospitals. As with Greenville Medical, the Washington hospital acknowledged that its HCDs had been found contaminated with the offending bacteria but stopped short of saying that the device was responsible for the infection or deaths.

In the other cases, the link is more certain. The CDC compared the bacteria found in heater-cooler devices in Pennsylvania and Iowa with the bacteria found in patients at those hospitals and found that all samples had the same genetic fingerprint. The agency concluded that those heater-coolers (all of them Stöckert 3T) were contaminated by the same source of water, most likely at the factory.

The same day the CDC issued its October advisory, LivaNova released a statement to its customers acknowledging the concerns raised. The company told Consumer Reports that it is "working closely" with stakeholders to resolve the problem while pointing out that heater-coolers are not easily replaced: "Without these devices, hospitals would be unable to perform many of the hundreds of thousands of heart surgeries needed by patients each year."

A Question of Transparency

In early June, the FDA convened a two-day meeting to discuss the HCD problem and to come up with recommendations for how to handle it. Several panel members argued that alerting all patients who underwent surgeries using an HCD might incite needless panic, or worse, scare very sick patients off of surgeries that could save their lives.

Concerns over cost were also raised: Richard Hopkins, M.D., a cardiac surgeon at Children's Mercy Academic Medical Center in Kansas City, Mo., said, "I'm a little loath to make a recommendation that's going to cost a hospital $1.5 million based on one case."

But not everyone agreed. Jonathan Zenilman, M.D., chief of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, suggested that even "one case" of NTM infection could qualify as an outbreak and could trigger a wide alert.

And Laurence Givner, M.D., a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., argued that all patients who have surgery with an HCD should be warned of the risk.

Ultimately, the panel recommended that providers be notified first and that patient notifications be limited. "If a facility discovers one patient infection, the panel does not recommend notifying all patients," the meeting summary states. The panel was "more receptive" to the idea of notifying all patients after two infections but suggested that if a hospital could determine exactly which patients had been in an operating room with a contaminated HCD, then only those patients should be notified.

Lisa McGiffert, director of Consumer Reports' Safe Patient Project, says that's not enough. "The CDC and FDA should call more forcefully on hospitals to inform all patients of the risk associated with heater-coolers before surgery," she says. "Without that awareness, patients don't know what symptoms to watch out for, or if and when to get tested for this rare infection."

Bell says that although both agencies can issue guidelines, neither the FDA nor the CDC has the power to compel hospitals to notify patients. "Those powers live at the state level," he says. "So any mandate really has to come from individual hospitals working with state health departments."

Hospitals and device-makers are required to report incidents to the FDA, but not to notify patients. And Lawrence Muscarella, Ph.D., a medical-device expert, says there is an alarming gap between what's reported to the agency and what's shared with patients.

"There are infection clusters in the FDA database that have not been publicly acknowledged," he says. "And we have no idea whether those hospitals are taking any steps to inform patients or address the problem." (Hospitals are not named in the FDA database.)

Attacking the Problem

Some hospitals are responding aggressively. In January 2015, when the University of Iowa Medical Center detected NTM in a heart-surgery patient who had valve-replacement surgery, the hospital convened an emergency response team made up of experts from every relevant department—including infection control, lab testing, surgery, and cardiology.

Within two weeks, the team had sent samples from all of the hospital's HCDs out for testing and had developed a "workaround" that involved drilling holes through its operating room walls so that the devices could be kept away from patients but still be used in surgeries. "It was a busy couple of weeks," says Daniel Diekema, M.D., director of the hospital's division of infectious diseases.

The hospital used billing codes and surgical logs to develop a list of all patients who had been exposed to a heater-cooler device, going back five years to account for the long lag time of some NTM infections. It identified 1,500 patients. "We decided to notify all of them," Edmond says. "We even notified the patients where the device wasn't used but was running on standby during their surgery."

They also created an alert in their electronic medical record system that pops up for any patient who develops symptoms of NTM infection after bypass surgery. The alert advises clinicians to order NTM tests and an infectious disease consult.

Those steps go well beyond what the CDC and FDA have recommended—including that hospitals follow strict HCD cleaning protocols, that they direct the device's exhaust fan away from the operating table, and that, should any heater-coolers test positive for bacterial contamination, they look back through lab records to check for cases of NTM.

But Edmond says the federal guidelines fall short of what's needed. "You're not going to find many NTM cases by just passively looking back through lab records," he says. "You have to be more proactive than that."

Symptoms and Safety Precautions

Consumer Reports suggests that patients undergoing heart or lung surgery ask their physicians whether the device will be used for their operations, and if so, whether it has been tested for contamination or implicated in any outbreaks.

If you've already had heart surgery, you and your doctor should be on the lookout for signs of infection, including irritation around the surgical incision, and unexplained fevers, night sweats, muscle aches, or weight loss, which can emerge as long as four years after surgery.

Lori Weinacker says she wishes she had known about the risks. "I assumed for open-heart surgery, everything is going to be clean, spotless, sterile," she says. "And they didn't tell us, and they didn't tell anyone else, that there's a slight chance that this is not the case."

Protecting Patients: What Needs to Change

- Consumer Reports' Safe Patient Project says that to better protect patients from infections related to heater-cooler devices, heart surgeons, hospitals, and the FDA should take the following steps:

- Surgeons should inform prospective patients of the risk of these infections and the symptoms they should be alert to.

- Hospitals should notify all patients who have been exposed to these heater-cooler devices in the past five years about the potential risk of infection.

- Hospitals should report infection outbreaks to exposed patients, healthcare providers, local and federal health officials, and the public as soon as they are identified.

- The FDA should review every medical device submitted for approval or clearance for infection control issues.

- Every hospital should take immediate steps to move the device outside of the operating room.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article was originally published October 13, 2016, under the headline "The Frightening New Risk in Heart Surgery." The current story has been updated to reflect additional information from the CDC, FDA, device-makers, and several hospitals, and will appear in the February 2017 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.