Unless the next director of the Central Intelligence Agency changes course, the CIA is going to face a season of cynicism and suspicion next November when the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy approaches and the public learns that the agency is withholding from public view more than 1,100 documents related to his assassination.

What will John Brennan do? That's a fair question for President Obama's nominee for CIA director at his upcoming confirmation hearings where issues of transparency and accountability are likely to dominate.

As national security adviser, Brennan made news last May by becoming the first U.S. official to acknowledge the U.S. government's drone war against suspected terrorists in Pakistan, Yemen and elsewhere. Brennan won kudos for his candor from supporters of the drone war, while critics found his claims of "moral rectitude" to be dubious in the absence of any checks on his power to target suspected terrorists (and inevitably innocent bystanders.)

Brennan's confirmation hearings are a rare opportunity for the Congress to hold the Executive Branch accountable for its secret actions. Brennan is reported to favor a more restrained drone war while liberal critics will seek disclosure of the legal justification for the extra-judicial assassination of U.S. citizens suspected of terrorism.

The overarching issue at stake in Brennan's confirmation is official secrecy in the name of national security. Do the White House and national security agencies acknowledge any limits on their powers of official secrecy? How can a self-governing democracy prevent the abuse of power without disclosure and accountability?

The JFK assassination story provides a useful benchmark in this debate because it is one area where a broad consensus holds that secrecy is not appropriate. If the Congress wants to demonstrate that it has the power to insure accountability at Obama's CIA, the JFK assassination records are a good place to start.

Congress did just that in 1992. In response to the furor raised by Oliver Stone's JFK, a Democratic Congress unanimously approved the JFK Records Act mandating "immediate" disclosure of all of the government's JFK files. A Republican president, George H.W. Bush, signed it into law.

The Act created a civilian review panel, the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB), to redress excessive secrecy surrounding the government's assassination-related records.

To its credit, the CIA cooperated and the ARRB won generally high marks from scholars and public interest groups. The Center for Effective Government hailed the law for creating a "presumption of disclosure" in declassifying four million pages of JFK records between 1994 and 1998 without any harm to U.S. national security.

The new JFK records go along way toward establishing a measure of historic accountability by providing a sobering new perspective on the causes of JFK's death. We now know that November 22, 1963 was a much more profound and preventable intelligence failure than U.S. national security agencies have ever acknowledged.

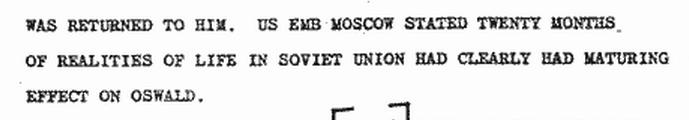

Contrary to what the Warren Commission told the American people in 1964, the CIA monitored the accused assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, constantly from October 1959 to October 1963. Indeed, one CIA cable -- not fully declassified until 2001-- shows that Oswald's travels, politics, and state of mind were the subject of discussion among senior agency officers just six weeks before JFK was killed. These officers (identified by name on the last page of the cable) concluded that Oswald was "maturing."

(Six weeks before JFK was killed, six top CIA officials signed off on a cable stating that Lee Harvey Oswald was "maturing.")

This reassuring and inaccurate message kept the CIA's Mexico City station in the dark about the fact that Oswald had gone public with support for a pro-Castro group and had recently been arrested for fighting with anti-Castro exiles in New Orleans. In Washington, a senior FBI official responded to one version of the CIA's benign assessment by taking Oswald's name off an "alert" list of people of special interest to the Bureau. Thanks to the CIA, the U.S. government relaxed its surveillance of Oswald in the same week that he made his way to Dallas.

Forty-four days later, JFK was shot dead, allegedly by the "maturing" Oswald.

Whether this cable embodies CIA incompetence or treachery is still a matter of debate. What is certain is that after JFK's death, CIA officials manipulated intelligence to plead a false ignorance about Oswald's travels and contacts. They relied on official secrecy to evade accountability and retain their positions of power. This same manipulation of intelligence and evasion of responsibility would recur at the CIA in the Iran-contra scandal of the 1980s and the run-up to the war in Iraq and its disastrous aftermath.

But the congressional mandate of full JFK disclosure did have benefits, if only belatedly. The new records have enhanced public understanding of the JFK story by revealing a middle ground in the perennial debate between conspiracy theorists and anti-conspiracy theorists about who was responsible for JFK's wrongful death. In a recent piece for theatlantic.com I suggested that the new records indicate two top CIA officials, deputy CIA director Richard Helms and counterintelligence chief James Angleton, may have been guilty of criminal negligence in JFK's death -- with the caveat that key records that might clarify the issue remain classified.

This is where Brennan comes in. The CIA retains at least 1,100 JFK documents that it says it will not release in any form. These documents, located but not reviewed closely by the ARRB in 1998, are the U.S. government's last officially recognized batch of JFK secrets. With the creation of the National Declassification Center (NDC), the Obama administration is now pushing an ambitious campaign to release 404 million unnecessarily secret government documents by 2014. These JFK records are an obvious candidate for review and release. Does the next director of the CIA agree or disagree?

The public's preference is clear. When the NDC solicited comment, more people cited the JFK records as a declassification priority than any other group of records. To date, almost 2,300 people have signed a Change.org online petition calling for the release of the records.

But when CIA refused to review the records, the NDC hastily repudiated the public input it had solicited. At a public meeting last August, the director of the NDC announced the 1,100 JFK records would not be reviewed or released until 2017, and maybe not then.

An all-too familiar fog of secrecy has descended on the subject. At the August meeting, a CIA representative to the NDC brazenly refused to answer any questions from the public about the agency's JFK records. In a dubious display of the art of Washington back-scratching, the general counsel of the National Archives, Gary Stern, stepped up to the podium and mouthed the CIA talking point that the agency doesn't have the "sufficient time or resources" to review these ancient records. (You can view video of the August event here. Stern speaks around 1:35:00.)

But on the 50th anniversary of JFK's assassination, the CIA is not going to be able to palm off questions about its peculiar priorities on junior bureaucratic enablers. The agency publicly boasts that it is supporting the NDC by declassifying records related to Berlin Wall crisis of 1961 and the massacre of Polish military officers in the Katyn Forest in 1942.

Next fall the CIA's director will have to defend the claim that such records are a higher priority for public release than files related to the assassination of a sitting U.S. president. Come November 22, 2013, the CIA's position will amount to: "We honor your memory, President Kennedy. Sorry, we don't have the time or resources to make public our secret files related to your murder."

That argument is not likely to impress the Kennedy family, much less an already suspicious public. (A 2003 Gallup poll found 34 percent of respondents thought the CIA was responsible for JFK's assassination.) Indeed, insisting on eternal JFK secrecy at this late date is a recipe for more controversy, conspiracy mongering, and suspicion.

There is no need for John Brennan to defend the indefensible and there is no need for the Congress or the public to accept anything less than full disclosure around JFK's assassination. Rather, there is a simple and popular way for Brennan to uphold the principles of transparency and accountability: Commit the CIA to releasing its last JFK secrets in time for the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of JFK's assassination next fall.