The video is a peculiar affair: a portly figure, heavily bearded, inspects his Islamist fighters in the northern Malian desert. Taken at the beginning of the year and posted on YouTube, much of the 12 or so minutes is taken up with prayer, interspersed with shots of fighters attacking the small garrison at Aguelhok and shots of dead soldiers.

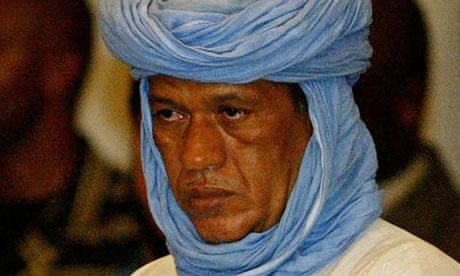

The man pictured is Iyad Ag Ghaly – nicknamed "the strategist" – the Tuareg Islamist leader of Ansar Dine, the "defenders of the faith". It is this man's actions in the coming weeks that might determine whether there is a foreign-led intervention in Mali against him and his allies – al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Mujao (the Movement for Openness and Jihad in West Africa).

Earlier this year it was the alliance of these three groups – Ansar Dine, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Mujao – that captured large parts of Mali's north, including the cities of Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. Since then, they have imposed an unpopular and extreme interpretation of sharia law that has seen stonings, amputations and the destruction of shrines.

With the growing threat of an African Union-led intervention to retake the north, backed by the European Union and the US, the quixotic figure of Ag Ghaly has emerged as the focus of attempts to avoid a wider conflict by persuading him to swap sides.

Last week, as a delegation from the rival Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) was in Paris to press its case, it emerged that discussions are focusing increasingly on Ag Ghaly. It is perhaps not surprising, given his record. For while Ag Ghaly has worked hard to reinvent himself as a hardline Islamist leader, it was not always the case for a man long noted for his fondness for whisky and music. As a leaked US embassy cable suggested, Ag Ghaly has a reputation for self-interest, describing how he had long sought to "play both sides … to maximise his personal gain".

The complicated tribal politics of northern Mali and the Sahel region have long set both rival tribes and competing social groups against each other. As the author of the leaked US cable in 2008 observed, what that meant in the 1990s was an "alphabet soup" of nationalist groups with different tribal attachments in an area the size of France, including, more recently, al-Qaida affiliates with financial interests in kidnapping and smuggling.

All that changed with the destabilising influence of the war in Libya that led to a flood of weapons into Mali, a military coup in the capital, Bamako, and the rebellion in the north, led first by the MNLA, a new group in which Ag Ghaly had sought a leadership role but had been rebuffed. The response of the quietly spoken tribal "aristocrat", say analysts, was to set up Ansar Dine as a rival group, forming an alliance of convenience with al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Mujao. It was a split that came to a head in March, when Ag Ghaly's rival rebels accused him of undermining the cause with his Islamist proclamations, calling him a "criminal" who wanted to found a "theocratic state".

In evidence to the US House foreign affairs committee earlier this year, Rudolph Atallah of the Atlantic Council, who has spent much time in northern Mali, said Ag Ghaly's split with other Tuareg leaders to found Ansar Dine meant Mali was "becoming a magnet for foreign fighters, who are flocking in to train recruits to use sophisticated weapons, built for and taken from [Muammar] Gaddafi's arsenal".

Ag Ghaly was born into a noble family in the Ifogha tribal group, who come from the Kidal region in the north. He travelled to Libya as a young man and joined Gaddafi's Islamic Legion, composed of exiles from the Sahel, whom Gaddafi used as cannon fodder in his conflict with Chad. He returned to Mali in 1990 to join the Tuareg uprising as a leader, later acting as a negotiator between the Malian government and the rebels.

His interest in the fundamentalist Salafist branch of Islam emerged, according to a profile in the French magazine L'Express, at the end of the 1990s, when he encountered Pakistani practitioners in Kidal at the same time as he was emerging as an intermediary for Islamist kidnappers, a profitable business from which he took a cut of the ransom. Ag Ghaly's contacts with the Islamists who would later form the core of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb were strengthened by the fact that a "cousin" was a leader of one of the groups.

Ag Ghaly also managed to maintain a working relationship with the former Malian president, Amadou Toumani Touré, persuading him to post him as the envoy to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, a closeness that was behind his rejection as a leader by rebels in the MNLA.

Now, however, Ag Ghaly is facing his greatest challenge. The lightning success of Islamist gains in Mali's north has gone down badly with many in the region. In a grand tour of the north to build support he was rebuffed by tribal leaders.

Other reports – impossible to verify – have suggested that even in his own fiefdom of Kidal his imposition of sharia law has proved deeply unpopular and he is running short of cash, while his group is suffering defections.

A UN security council resolution has authorised the formation of an African Union-led military expedition to recapture the north, while France, Germany and the US have offered logistical assistance. Algeria, which had been resisting any intervention, said that it would accept it as a "last resort" as long as it did not set foot on Algerian soil in hunting fighters.

Patrick Smith of the Africa Confidential newsletter, who was in Paris after the MNLA delegation, believes Ag Ghaly will be offered a choice. "There's a growing desire to reach out to him to say you can ally with us and help work out a deal for a decentralised north. If not, it's war and you'll end up on a list with other al-Qaida-associated leaders wondering when a drone is coming for you."

Smith, like other analysts, believes that Ag Ghaly is more interested in power than founding a "theocratic state" in Mali. "When he was manoeuvring for a leadership position in the MNLA there was no question of a theocratic state."

Another western analyst said: "Iyad Ag Ghaly is regarded as a big man, a pragmatist who is willing to do deals."

John Campbell, a Mali watcher at the US Council on Foreign Relations, doubts there will be conflict, despite the drumbeats suggesting an imminent military intervention. He believes that a negotiation is more likely, at least involving Ag Ghaly and his followers. "I think the way forward is political dialogue."

Most, however, accept that, even if Ag Ghaly is persuaded to talk, and split from al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb in exchange for more autonomy for the north, that would still leave the issue of al-Qaida and its foreign fighters, including Algerians and Sudanese. The Algerian decision to accept that a military intervention may be inevitable, after weeks of diplomatic pressure from France, might just be the leverage to persuade the Tuareg leader to change his mind.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion