Reel Faith: How the Drive-In Movie Theater Helped Create the Megachurch

The startup origins of the Crystal Cathedral

![[optional image description]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/media/mt/science/CrystalCathedral.jpeg)

The Crystal Cathedral rises like a spaceship out of an impossibly green lawn in Garden Grove, Orange County, California. The structure is neither crystal nor, technically, a cathedral, but it's acted as an archetype for a 20th century phenomenon: the Christian megachurch. From the church's soaring, sunlit pulpit, the charismatic preacher Reverend Robert Schuller spoke to a sea of worshippers -- not just to congregants in the cavernous room itself, his image amplified by a JumboTron, but also, eventually, to a much wider audience via the church's iconic Hour of Power reality show. If Christianity exists to be spread, the Cathedral has existed to do that spreading. It's been at once a place of worship and a TV studio.

The Crystal Cathedral has been in the news most recently for its financial troubles -- culminating in bankruptcy, a controversial shift in the the church's leadership structure, and, finally, the sale of the Cathedral itself to a neighboring (Catholic) diocese. Today, the church ministry announced that the congregation will be moving its services a smaller building, a currently Catholic church, a mile down the road from the Cathedral's compound. In that, the Cathedral also seems symbolic of its times.

But if a church is a kind of technology -- of media, of communication, of community -- then it's fitting that even a megachurch would have a humble startup story. And the origins of the Crystal Cathedral, for all its shine and swagger, are more garage than skyscraper.

In 1955, the Reformed Church in America gave a grant of $500 to Reverend Schuller and his wife Arvella. The young couple were to start a ministry in California; for that, they needed to find a venue that would host their notional congregation. While making the trip from Illinois, driving on Route 66, the reverend took to a napkin and listed 10 sites that could host his budding ministry. Researching the matter further, however, Schuller discovered that the first nine of those options were already in use for other purposes. So he set his sights on the tenth: the Orange Drive-In Theatre.

The efficiencies of the venue were obvious: For cinematic purposes, the drive-in was useful only in the darkness, which meant that it could play an effortlessly dual role, theater by night and church by day. The architecture and technological system built for entertainment could be repurposed, hacked even, to deliver a religious ceremony for the golden age of the car. An early advertisement announced the new ministry's appeal: "The Orange Church meets in the Orange Drive-In Theater where even the handicapped, hard of hearing, aged and infirm can see and hear the entire service without leaving their family car."

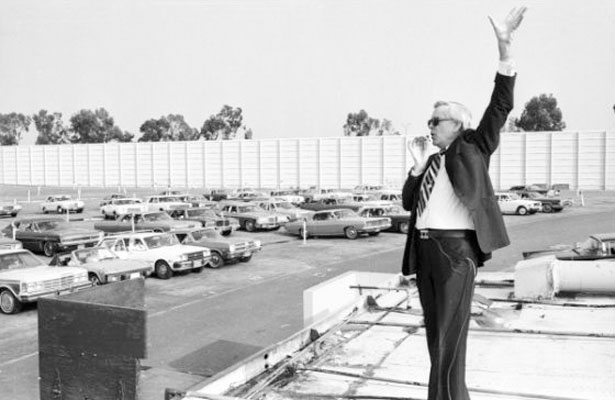

As the Schullers embraced their makeshift new venue, the congregation, in turn, came to embrace them. Disneyland had just opened a couple miles down the road from the Orange, in Anaheim; the entire area was developing rapidly. Each week, Reverend Schuller led a growing group of car-confined congregants from the tar paper roof of the theater's snack bar; you can see him mid-sermon below thanks to an Orange County Register photographer. Arvella provided music for each service from an electronic organ mounted on a trailer. Worshippers listened to them via portable speakerboxes mounted to their vehicles. Church rubrics, the guidebooks for services, included instructions not only about when to sing, speak, and stay silent, but also for mounting the speakers onto car windows.

The Schullers, and their contemporary entrepreneurs of religiosity, had happened into an idea that made particular cultural sense at its particular cultural moment: In the mid-1950s, Americans found themselves in the honeymoon stages of their romances with both the automobile and the television. And they found themselves seeking forms of fellowship that mirrored the community and individuality that those technologies encouraged. As one former congregant put it: "Smoke and be in church at the same time, at a drive-in during the daytime. What a trip!"

Drive-in theaters, the historian Erica Robles-Anderson says, were a kind of stop-gap technology: a fusion of the privacy and publicness that cars and TVs engendered. (And they'd long had unique by-day identities -- as makeshift amusement parks, as venues for traveling flea markets, as theaters for traveling Vaudeville acts and the acts that advertised them.) We tend to think of suburbs, Robles-Anderson told me, as symbols of the collapse of civic life; drive-ins, however, represented a certain reclaiming of it. And a drive-in church service was an extension of that reclamation. It was, with its peculiar yet practical combination of openness and enclosure, an improvised idea that happened to fit its time. The Schullers' motto? "Come as you are in the family car."

As the size of the Orange Drive-In congregation grew, Schuller set his sights toward expansion, purchasing a 10-acre plot of land in nearby Garden Grove, California. He began construction on a venue that would feature not only a classically physical church, but also a 500-car parking lot to continue the drive-in tradition. The compound would be designed by the architect Richard Neutra, who was known for open-air structures that emphasized the fluidity between interior and exterior. The building -- the Garden Grove Community Drive-In Church -- would combine the appeal of the car-friendly service with the tradition of indoor worship: It would employ a "walk-in, drive-in" approach that would allow congregants either to sit indoors, in pews, or to park their cars outside of the church, listening in remotely. In either case, the ceremony would center around Schuller, who preached on a stage-like balcony built into the corner of the church's exterior wall.

![[optional image description]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/media/mt/science/6207-GardenGroveDriveInChurch-Interior.jpeg)

In 1968, as the congregation -- and Orange County -- continued to grow, Schuller purchased another 10-acre plot: a walnut grove that bordered the north side of the Garden Grove church. The new church would be designed by the architect Philip Johnson. It would be soaring and striking. It would be constructed entirely of glass.

Today, as the congregation of the Crystal Cathedral prepares to move away from the church it's called home, and as a new congregation prepares to move in, the building is a reminder of what's reassuring and problematic about solid structures: they don't move. But people do. The Cathedral's current congregation is doing with pain what its predecessors did with ease half a century ago: driving away.