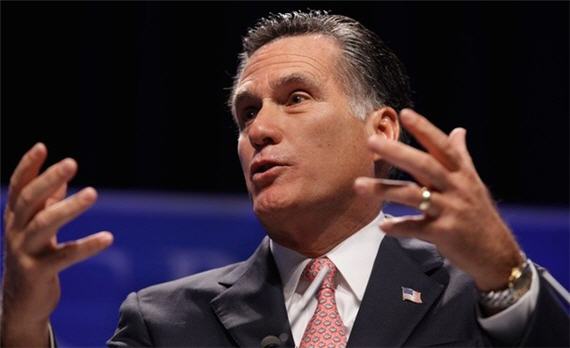

Dissecting Mitt Romney’s Foreign Policy

Is there a Romney Doctrine?

While the Sunday morning shows today have been obsessed, predictably enough, with President Obama’s statement on same-sex marriage and the political ramifications thereof, David Sanger is out with an interesting news analysis in The New York Times trying to determine the answer to the question, is there such a thing as a Romney Doctrine when it comes to foreign policy:

During the Republican primary debates in January, when Mitt Romney was still trying to outmaneuver the challengers who were questioning his conservative bona fides, he made a declaration about Afghanistan that led a faction of his foreign policy advisers to shake their heads in wonderment.

“We should not negotiate with the Taliban,” the former Massachusetts governor declared, just as diplomats dispatched by the president were in Qatar trying to get those negotiations going. “We should defeat the Taliban.” In case anyone missed his meaning, he drove home the point, saying the best strategy was, “We go anywhere they are and we kill them.”

Set aside for the moment that many of Mr. Romney’s supporters and foreign policy advisers argue that after a decade at war, the only option is a political settlement, which means talking to some elements of the Taliban. Stephen Hadley, the former national security adviser to George W. Bush, has argued this “would not — as some have suggested — constitute ‘surrender’ to America’s enemies.” A co-chairman of Mr. Romney’s working group on Afghanistan and Pakistan, James Shinn, who also served Mr. Bush, was co-author of perhaps the best single unclassified document on the complexities of those negotiations, entitled “Afghan Peace Talks: A Primer.” It argued that a negotiated deal would “obviously be desirable” if elements of the Taliban could be persuaded to renounce violence and take “some role in Afghan governance short of total control.”

It was just one example of what Mr. Romney’s advisers call a perplexing pattern: Dozens of subtle position papers flow through the candidate’s policy shop and yet seem to have little influence on Mr. Romney’s hawkish-sounding pronouncements, on everything from war to nuclear proliferation to the trade-offs in dealing with China. In the Afghanistan case, “none of us could quite figure out what he was advocating,” one of Mr. Romney’s advisers said. He insisted on anonymity — as did a half-dozen others interviewed over the past two weeks — because the Romney campaign has banned any discussion of the process by which the candidate formulates his positions.

“It begged the obvious question,” the adviser added. “Do we stay another decade? How many forces, and how long, does that take? Do we really want to go into the general election telling Americans that we should stay a few more years to eradicate the whole Taliban movement?” In phase one of a long presidential campaign, Mr. Romney could duck those questions: the spotlight moved to the wisdom of the economic stimulus and the auto-industry bailout, contraception and, now, same-sex marriage and high school bullying.

Those comments about Obama’s decision to go forward with negotiations with the Taliban aren’t the only time that Romney seemed to make odd comments about complex foreign policy issues during the course of the primary campaign. Most recently, he asserted that Russia is American’s “Number One” strategic foe in the world. In February, he said that the decision to begin the planned drawn down of American (and allied) forces in Afghanistan constituted a decision that put our military mission in the country “in jeopardy.” In a debate in Florida in January, Romney presented perhaps the most radical view ever of the U.S.-Israeli relationship when he said, “We will not have an inch of difference between ourselves and our ally, Israel.” During one debate, he said that as President he would take China before the WTO for currency manipulation despite the fact, as Jon Huntman pointed out that night, that the WTO Treaty doesn’t allow for complaints to be filed on monetary issues alone. More generally Romney has been among those candidates who accused the President of following a worldwide policy of appeasement, and repeating the generally false claim that the President has spent his time in office apologizing for America.

Perhaps the one area where Romney has tried to differentiate himself from the President the most, though, has been on the issue of Iran and its nuclear weapons program, as he made clear in a March Op-Ed in The Washington Post:

As for Iran in particular, I will take every measure necessary to check the evil regime of the ayatollahs. Until Iran ceases its nuclear-bomb program, I will press for ever-tightening sanctions, acting with other countries if we can but alone if we must. I will speak out on behalf of the cause of democracy in Iran and support Iranian dissidents who are fighting for their freedom. I will make clear that America’s commitment to Israel’s security and survival is absolute. I will demonstrate our commitment to the world by making Jerusalem the destination of my first foreign trip.

Most important, I will buttress my diplomacy with a military option that will persuade the ayatollahs to abandon their nuclear ambitions. Only when they understand that at the end of that road lies not nuclear weapons but ruin will there be a real chance for a peaceful resolution.

My plan includes restoring the regular presence of aircraft carrier groups in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf region simultaneously. It also includes increasing military assistance to Israel and improved coordination with all of our allies in the area.

We can’t afford to wait much longer, and we certainly can’t afford to wait through four more years of an Obama administration. By then it will be far too late. If the Iranians are permitted to get the bomb, the consequences will be as uncontrollable as they are horrendous. My foreign policy plan to avert this catastrophe is plain: Either the ayatollahs will get the message, or they will learn some very painful lessons about the meaning of American resolve.

It’s fairly strong rhetoric, and Romney would like us to think that it is indeed different from what he characterizes the weak position of the Obama Administration, but in reality there are far more similarities between Romney and Obama on Iran, and indeed on foreign policy in general, than there are differences. Part of this may be a reflection of the fact that Romney’s own foreign policy advisers aren’t entirely in agreement on many of these issues:

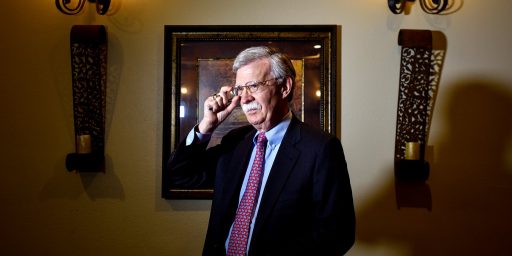

On these questions, Mr. Romney’s own advisers, judging by their public writing and comments, possess widely differing views — often a result of the scar tissue they developed in Iraq, Afghanistan and other Bush-era experiments in the exercise of American power. But what has struck both his advisers and outside Republicans is that in his effort to secure the nomination, Mr. Romney’s public comments have usually rejected mainstream Republican orthodoxy. They sound more like the talking points of the neoconservatives — the “Bolton faction,” as insiders call the group led by John Bolton, the former ambassador to the United Nations. In a stormy tenure in the Bush administration, Mr. Bolton was often arguing that international institutions, the United Nations included, should be routed around because they so often frustrate American interests.

Curiously for a Republican candidate with virtually no foreign policy record, Mr. Romney has made little effort to court the old-timers of Republican internationalism, from the former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft to the former secretaries of state James A. Baker III, George P. Shultz and even the grandmaster of realism, Henry A. Kissinger. And in seeking to define himself in opposition to President Obama, Mr. Romney has openly rejected positions that George W. Bush came around to in his humbler second term.

This may change as the arrival of the general election requires Mr. Romney to grapple with the question of how to attack a Democratic president whose affection for unilateral use of force — from drones over Pakistan and Yemen to a far greater role for the Special Operations command — has immunized him a bit from the traditional claim that Democrats can’t stand the sight of hard power. So far Mr. Romney’s most nuanced line of attack was laid out in the introduction to a campaign white paper last fall written by Eliot Cohen, a historian and security expert who worked for Condoleezza Rice in the State Department, that the “high council of the Obama administration” views the “United States as a power in decline,” a “condition that can and should be managed for the global good rather than reversed.” It also alleged a “torrent of criticism, unprecedented for an American president, that Barack Obama has directed at his own country.”

But in a campaign likely to be dominated by a slow-burning nuclear crisis with Iran, the likelihood of a North Korean nuclear test, the kind of eruptions with China that have dominated headlines for the past two weeks and the end of the surge in Afghanistan come September, the internal struggles between the various factions within the Romney campaign are likely to become evident.

On some level it isn’t a bad thing that Romney is getting advice from a wide variety of sources. At the very least, it’s good to have some voices whispering in his ear to counter the neoconservativism of the Bolton faction, although one wonders why that particular world view is even taken seriously at this point. However, if it he wins, it’s going to be Mitt Romney’s job to be the one to make a decision, which is why his own overall view of the world matters. To the extent we know anything about that, it appears that he leans far too much in the neoconservative direction but that may be as much a function of his need to appeal to the Republican base as it is any reflection of his core beliefs on these issues. Sanger closes his article that pointing out that “[t]he Romney strategy for now may simply be to portray Mr. Obama as a weak apologizer and figure out the details later.” That makes some sense politically, and one certainly doesn’t expect detailed dissertations on issues that diplomats and military advisers continue to spend endless hours pondering, but it would be nice if, at the very least, we had some idea of which way Romney leans, even in an election where the primary focus will be on economic issues. So far, we’re not really getting that.

It’s always the same problem with Romney: Who the hell knows what he thinks?

Right now, the Romney Foreign Policy Doctrine seems to be:

James has tried to be reassuring on this topic. Some of Romney’s advisers seem reasonable. However, his public rhetoric is almost pure neocon. While it is difficult to tell with Romney, I do think it more likely that he will put us at war with iran. I expect him to be more reasonable in the economic sphere, so I assume his statements on China are just meant to appease the base and make him sound tough.

Steve

You mean we can kill brown people AND make defense contractors rich? Wow.

Come now, that’s quite easy to determine. Which way is the wind blowing?

Funny how a Romney Campaign adviser like John Bolton continues to appear multiple times a day on FNC as a foreign policy expert, and never has to disclose his conflict of interest. Obviously the same has long applied to many others like Karl Rove appearing as simply a “Fox News contributor” political analyst instead of being identified as running the biggest GOP slushfund superPAC.

Is this going to be updated daily or weekly?

Because otherwise it may not be long until it’s rather outdated.

Who knows what positions Romney may have tomorrow.

Is it possible that Romney’s ambitions end with becoming president rather than what he would do as president?

I have no idea,what he would do with the power, but I am beginning to suspect that he doesn’t either. I don’t know whether this is better or worse than him running as a stealth candidate, knowing what he wants to do, but just never telling anyone and taking whatever position seems expedient at the time in the campaign.

Mitt Romney has but one core belief: He should be President. Everything else is as Michael said: Which way is the wind blowing?

His foreign policy is just like all Republican’ts positions on anything “If a Democrat is for it, then I’m against it” that is Republican’t political philosophy in a nutshell.

@Gustopher: Nailed it.

The fact that he’s going to increase the DOD budget by 2.1 trillion dollars should tell you something.

Either way, genuine or phony, we don’t need to be electing any more neocons to run the executive branch.