Practice Essentials

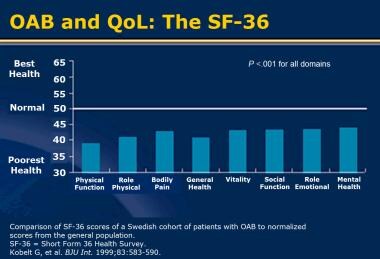

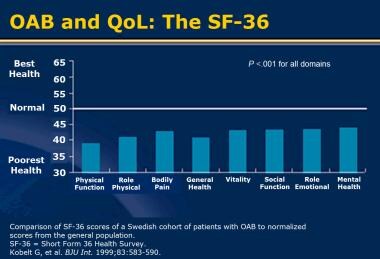

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a syndrome characterized by a sudden and compelling need to urinate. OAB affects physical functioning, social functioning, vitality, and emotional roles [1] (see the image below).

Overactive bladder (OAB) and quality of life (QoL). Short Form-36 (SF-36). Reprinted with permission from Blackwell.

Overactive bladder (OAB) and quality of life (QoL). Short Form-36 (SF-36). Reprinted with permission from Blackwell.

Signs and symptoms

Clinical manifestations of overactive bladder OAB include the following:

-

Urinary urgency (hallmark symptom)

-

Urgency urinary incontinence (may or may not be present)

-

Urinary frequency and nocturia (usually present)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of OAB requires exclusion of infection and other pathologic conditions. In complicated cases, demonstration of underlying detrusor overactivity (phasic increases in detrusor pressure) can be valuable.

Diagnostic guidelines

Guidelines for diagnosis of OAB by the American Urological Association (AUA)/Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) include the following [2] :

-

A thorough history, physical examination, and urinalysis should be done initially.

-

If necessary, a urine culture or postvoid residual assessment or both can be done, along with use of bladder diaries or symptom questionnaires.

-

Urodynamic study, cystoscopy, and diagnostic kidneys and bladder ultrasonography are not necessary in the initial workup of uncomplicated cases and should be reserved for refractory or otherwise complicated cases.

-

Urine cytology is not recommended in the absence of hematuria when the patient responds to therapy.

Examination and testing

A comprehensive physical examination for OAB includes the following:

-

Pulmonary and cardiovascular evaluation

-

Abdominal examination

-

Pelvic examination and rectal examination

-

Neurologic examination

Office and laboratory tests for OAB include the following:

-

Urinalysis

-

Urine culture (if infection is suspected)

-

Postvoid residual testing

-

Cystometry

-

Urodynamic study

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The three main treatment approaches are as follows:

-

Behavioral therapy (eg, bladder training, biofeedback, pelvic floor muscle therapy, pelvic floor electrical stimulation)

-

Pharmacologic therapy (eg, anticholinergic/antimuscarinic agents)

-

Surgical therapy (eg, neuromodulation and augmentation cytoplasty [rarely necessary])

Treatment guidelines

Guidelines for the treatment of OAB by the AUA/SUFU include the following recommendations [2] :

-

First-line therapy: Behavioral therapies and education should be offered first; starting antimuscarinic agents at the same time as behavior therapies may prove clinically beneficial.

-

Second-line therapy: Antimuscarinics; extended-release preparations should be used instead of immediate-release preparations when possible; transdermal oxybutynin can also be used.

-

Third-line therapy: Sacral neuromodulation or peripheral tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) for carefully selected patients with severe refractory OAB symptoms or those who are not candidates for second-line therapy and are willing to undergo a surgical procedure; intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA is another option.

Chronic incontinence

Recommendations for improving symptoms of chronic incontinence and reducing cost of care include the following:

-

Scheduled toileting

-

Prompted voiding

-

Improved access to toilets

-

Management of fluids and diet

-

Use of disposable absorbent pads or garments

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

For patient education information, see Overactive Bladder.

Background

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines overactive bladder (OAB) as a syndrome consisting of urinary urgency, with or without urgency urinary incontinence, usually with urinary frequency and nocturia, in the absence of causative infection or pathologic conditions and suggestive of underlying detrusor overactivity (phasic increases in detrusor pressure).

Urgency, the hallmark of OAB, is defined as the sudden compelling desire to urinate, a sensation that is difficult to defer. Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is urinary leakage associated with urgency. UUI is one of the most common types of urinary incontinence. Some women may have both stress urinary incontinence and UUI, and this is called mixed urinary incontinence.

Urinary frequency is defined as voiding 8 or more times in a 24-hour period. Nocturia is defined as the need to wake 1 or more times per night to void. [3]

The term OAB has been adopted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to expand the number and types of patients eligible for clinical trials. As noted, OAB may include not only urgency urinary incontinence but also urgency, frequency, dysuria, and nocturia. Other terms used include detrusor overactivity, detrusor instability, detrusor hyperreflexia, and involuntary bladder contractions.

A preliminary diagnosis of OAB can be made on the basis of the history and physical examination (see Presentation), in conjunction with a few simple office and laboratory tests (see Workup).

Treatment of OAB is aimed at reducing the debilitating symptoms in order to improve the overall quality of life in affected patients (see Treatment). Anticholinergic agents that target the muscarinic receptors in the bladder (antimuscarinic agents) are the pharmacologic treatment of choice because they reduce the contractility of the detrusor muscle. However, the use of antimuscarinic drugs is limited by certain adverse effects, particularly dry mouth and constipation.

Behavioral therapy focusing on dietary and lifestyle modification, voiding regimens, and pelvic floor muscle exercises is also helpful in the management of OAB and may be used by itself or in conjunction with antimuscarinic therapy.

Various attempts have been made to improve the bladder selectivity of these drugs, and thereby overcome the systemic adverse effects, as well as to come up with different formulations to lower peak levels of agents and avoid first-pass liver metabolism, which is often associated with an increased risk of adverse effects in some of these agents. These include the development of new antimuscarinic agents with structural modifications and the use of innovative drug-delivery methods.

The advancement in the drug-delivery systems extends to the long-term therapeutic efficacy, with improved tolerability and patient compliance; however, future prospective therapies are aimed at novel targets with novel mechanisms of action, including beta3-adrenoceptor agonists, K+ channel openers, and 5-HT modulators. [4] These prospective therapies are currently at different stages of clinical development.

Among other investigational therapies, neurokinin receptor antagonists, alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists, nerve growth factor inhibitors, gene therapy, and stem cell–based therapies are of considerable interest. The future development of new modalities in OAB treatment appears promising.

OAB affects children as well as adults. For more information, see Overactive Bladder in Children and Urinary Incontinence.

Anatomy and Physiology

A normal bladder functions through a complex coordination of musculoskeletal, neurologic, and psychological functions that allow it to fill and empty. The prime effector of continence is the synergic relaxation of detrusor muscles and contraction of bladder neck and pelvic floor muscles.

Various efferent and afferent neural pathways and neurotransmitters are involved. Central neurotransmitters (eg, glutamate, serotonin, and dopamine) are thought to have a role in urination. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter in pathways that control the lower urinary tract. Serotonergic pathways facilitate urine storage. Dopaminergic pathways may have both inhibitory and excitatory effects on urination. Dopamine D1 receptors appear to have a role in suppressing bladder activity, whereas dopamine D2 receptors appear to facilitate voiding.

In bladder filling, sympathetic nerve fibers that originate from the T11 to L2 segments of the spinal cord, which innervate smooth-muscle fibers around the bladder neck and proximal urethra, cause these fibers to contract, allowing the bladder to fill. As the bladder fills, sensory stretch receptors in the bladder wall trigger a central nervous system (CNS) response. During bladder filling, the intravesical pressure remains low as a result of the viscoelastic properties of the bladder and antagonism of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS).

The PNS causes contraction of the detrusor, while the muscles of the pelvic floor and external sphincter relax. The PNS fibers, as well as those responsible for somatic (voluntary) control of micturition (urination), originate from the S2 to S4 segments of the spinal cord in the sacral plexus. The somatic fibers innervate the external sphincter and are responsible for the voluntary control of continence in the face of a pressing desire to void.

The normal adult bladder accommodates 300-600 mL of urine; a CNS response is usually triggered when the volume reaches 400 mL However, urination can be prevented by cortical suppression of the PNS or by voluntary contraction of the external sphincter.

Pathophysiology

OAB appears to be multifactorial in both etiology and pathophysiology. Symptoms of OAB are suggestive of underlying detrusor overactivity. Overactivity of the detrusor muscle—neurogenic, myogenic, or idiopathic in origin—may result in urinary urgency and urgency incontinence. [5]

The role of the M2 muscarinic receptor subtype in the human bladder is not well established. Data from small studies demonstrating up-regulation of the M2 receptor in certain pathologic states suggest that it may have a role in detrusor overactivity related to obstruction and spinal cord injury.

Binding of acetylcholine to the M3 receptor activates phospholipase C via coupling with G proteins. This action causes the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and contraction of the bladder smooth muscle. Increased sensitivity to stimulation by muscarinic receptors may lead to OAB. Leakage of acetylcholine from the parasympathetic nerve terminal may lead to micromotion of the detrusor, which may activate sensory afferent fibers, leading to the sensation of urgency.

Sensory afferent nerves may also play a role in OAB. Activation of normally quiescent C sensory fibers may help produce symptoms of OAB in individuals with neurologic and other disorders. Several types of receptors identified on sensory nerves may have a role in OAB symptoms. These include vanilloid, purinergic, neurokinin A, and nerve growth factor receptors. Substances such as nitric oxide, calcitonin gene-related protein, and brain-derived neurotropic factor may also have a role in modulating sensory afferent fibers in the human bladder. [6]

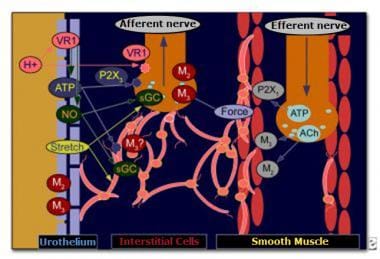

Once thought to be biologically inert, the urothelium may also have a role in OAB (see the image below). The urothelium communicates directly with suburothelial afferents acting as luminal sensors. Low pH, high potassium concentration, and increased osmolality in the urine can influence sensory nerves. Activation of suburothelial afferent fibers without changes in the smooth muscle may lead to urgency. Activation of the suburothelial afferents in the presence of enhanced smooth-muscle coupling may lead to urgency and unstable detrusor contractions. [7, 8]

Communication between urothelium and suburothelium. ACh—acetylcholine; ATP—adenosine triphosphate; M2—muscarinic receptor subtype 2; M3—muscarinic receptor subtype 3; NO—nitric oxide; P2X1—purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel 1; P2X3—purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel 3; sGC—soluble guanyl cyclase; VR1—vanilloid receptor 1.

Communication between urothelium and suburothelium. ACh—acetylcholine; ATP—adenosine triphosphate; M2—muscarinic receptor subtype 2; M3—muscarinic receptor subtype 3; NO—nitric oxide; P2X1—purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel 1; P2X3—purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel 3; sGC—soluble guanyl cyclase; VR1—vanilloid receptor 1.

Etiology

OAB is primarily a neuromuscular problem in which the detrusor muscle contracts inappropriately during bladder filling (ie, storage phase). These contractions often occur regardless of the amount of urine in the bladder. OAB may result from a number of different causes, both neurogenic and nonneurogenic.

Neurologic injuries that may cause OAB include the following:

-

Spinal cord injury

-

Stroke

Neurologic diseases that may cause OAB include the following:

-

Dementia

-

Medullary lesions

Detrusor overactivity can also occur in the absence of a neurogenic etiology. Contractions can be spontaneous or induced by rapid filling of the bladder, postural changes, or even walking or coughing. Because these causes are nonneurogenic, the pressing need to urinate can be contained for a few minutes after it is first sensed.

Idiopathic OAB is OAB in the absence of any underlying neurologic, metabolic, or other causes of OAB, or conditions that may mimic OAB, such as urinary tract infection, bladder cancer, bladder stones, bladder inflammation, or bladder outlet obstruction.

Certain medications may lead to symptoms of OAB. Diuretics can cause urge incontinence because of increased bladder filling, stimulating the detrusor. Bethanechol can also cause urge incontinence through its stimulation of bladder smooth-muscle contraction.

Heart failure or peripheral venous and vascular disease can also contribute to symptoms of OAB. During the day, such individuals have excess fluid collect in dependent positions (feet and ankles). When they recline to go to sleep, much of this fluid becomes mobilized and increases renal output, thereby increasing urine output. Many of these patients describe increased nocturia that manifests as OAB.

Only in rare cases does it prove impossible to identify a specific cause (idiopathic OAB).

Risk factors

Several risk factors are associated with OAB. White people, persons with insulin-dependent diabetes, and individuals with depression are 3 times as likely to develop OAB. Other risk factors include the following [9] :

-

Age > 75 years

-

Arthritis

-

Use of oral hormone replacement therapy

-

High body mass index (BMI)

The physiologic changes associated with aging, such as decreased bladder capacity and changes in muscle tone, favor the development of OAB when precipitating factors intervene. [10, 11, 12, 13, 14] In postmenopausal women, many of these changes are related to estrogen deficiency. Estrogen deprivation therapy in younger women with breast cancer has also been associated with increased risk for OAB. [15] Perhaps the most important age-related change in bladder function that leads to incontinence is the increased number of involuntary bladder contractions (detrusor instability).

Any disruption in the integration of musculoskeletal and neurologic responses can lead to loss of control of normal bladder function and to urge incontinence.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In the National Overactive Bladder Evaluation (NOBLE) study, which evaluated 5204 adults 18 years of age and older who were representative of the US population by sex, age, and geographical region, 16.5% of the study participants met the criteria for OAB. Of those, 6.1% met the criteria for OAB with urgency incontinence, and 10.4% met criteria for OAB without urgency incontinence. Among individuals with OAB with urgency incontinence, 45% had mixed incontinence symptoms (urgency incontinence plus stress incontinence). Data in the study were gathered with the use of a computer-assisted telephone interview questionnaire. [16]

International statistics

OAB affects millions of people worldwide, regardless of race. The frequency data on OAB found in Europe are similar to that found in the United States.

Age-related differences in incidence

The prevalence of OAB increases with age. However, OAB should not be considered a normal part of aging. Twenty percent of the population aged 70 years or older report symptoms of OAB; 30% of those aged 75 years or older report symptoms. Men tend to develop OAB slightly later in life than women do.

Sexual differences in incidence

In the NOBLE study, the prevalence of OAB was similar in women and men (16.9% and 16%, respectively). [16] However, the prevalence of incontinence associated with OAB differed. Among women, 9.3% reported having OAB with incontinence; 7.6% reported having OAB without incontinence. In contrast, more men reported having OAB without incontinence (13.4%) than with incontinence (2.6%). In women, the prevalence of OAB with urgency urinary incontinence increased with increasing body mass index (BMI), whereas in men, no difference was found.

Milsom et al, in a population-based survey (conducted by telephone or direct interview) of 16,776 men and women aged 40 years or older from the general population in Europe, found the overall prevalence of OAB symptoms to be 16.6%. [17] The main outcome measures included the prevalence of urinary frequency (> 8 micturitions per day), urinary urgency, and urgency incontinence.

Frequency was the most common symptom (85%), followed by urgency (54%) and urgency incontinence (36%). The prevalence of OAB increased with age, and rates in men and women were similar. Symptoms of urinary urgency and frequency were similar between both sexes, but urgency incontinence was more prevalent in women than in men.

OAB in men is often related to obstruction; therefore, it may be important to differentiate between obstruction and irritative symptoms before the initiation of treatment.

Prognosis

Behavioral therapy combined with pharmacologic therapy offers good results in OAB patients, with up to 80% of cases improved and excellent long-term results.

OAB can have devastating effects on quality of life (QoL), [18, 19] but its impact is not limited to this (as is often mistakenly assumed). Urinary incontinence remains one of the most common indications for admission to nursing homes. In addition, OAB and urinary incontinence are associated with other medical comorbidities, such as urinary tract infection (UTI); skin infection and irritation; and, in elderly persons, an increased risk of falls and fractures [20] (see Presentation). The economic impact of OAB is also considerable. [21]

Impact on quality of life

OAB significantly impairs QoL, increases depression scores, and reduces quality of sleep. OAB that involves urgency incontinence is associated with the most severe impairment. Persons with OAB who have poor sleep quality report chronic fatigue and difficulty performing daily activities. An increased number of hip fractures due to falls in elderly persons have been attributed to OAB because of the nocturia component. Many such falls involve the individual tripping or losing balance while getting out of bed.

Individuals with OAB develop coping strategies to manage or hide their problems (eg, modifying fluid intake, toilet mapping, reduced physical or social activity). These coping strategies, along with the OAB symptoms themselves, commonly affect interactions with friends, colleagues, and families and thereby have an adverse impact on QoL.

Notable psychological effects of OAB and urinary incontinence include fear, shame, and guilt. In elderly people with OAB and incontinence, the need for assistance with toileting, shopping for protective undergarments, and laundry may place an additional burden on family members.

Worries and concerns regarding odor, uncleanliness, and leakage during sexual activity may lead individuals to refrain from intimacy. Frequent urination and the need to interrupt activities may affect the person’s work and ability to travel. Studies of the impact of OAB and urinary incontinence demonstrate decreased levels of social and personal activities, increased psychological distress, and an overall decrease in QoL. [16]

The impact of OAB on QoL is independent of whether the symptoms are associated with urinary incontinence. Studies with the Short Form-36 (SF-36), a generic QoL questionnaire, demonstrated that OAB affects physical functioning, social functioning, vitality, and emotional roles (see the image below). A shortened form of the SF-36, the Short Form-20 (SF-20), is another reliable and valid instrument for measuring health-related QoL. [22]

Overactive bladder (OAB) and quality of life (QoL). Short Form-36 (SF-36). Reprinted with permission from Blackwell.

Overactive bladder (OAB) and quality of life (QoL). Short Form-36 (SF-36). Reprinted with permission from Blackwell.

Validated instruments that assess disease-specific QoL, such as the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ), the Kings Health Questionnaire, and the OAB-q, have been developed to determine the impact of OAB and urinary incontinence on QoL. These have all demonstrated the substantial impact of OAB and urinary incontinence.

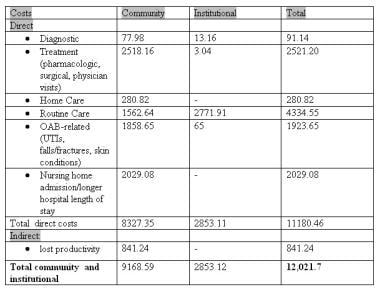

The prevalence of OAB increases with age, and as many as 50% of nursing-home residents have either OAB or urinary incontinence. The annual cost of managing OAB in long-term care facilities has been estimated to exceed $3 billion; this figure increases to an estimated $9 billion in the community setting.

Jayadevappa et al documented an increased risk of falls and fractures in elderly patients with OAB. In a review of Medicare data from 2006 to 2010 that included 33,631 enrollees with OAB (mean age, 77.8 years), the proportion of patients who had falls was higher in those with OAB than in those without OAB (11% vs 7%, respectively; P < 0.001). Treatment for OAB was associated with lower likelihood of falls (odds ratio [OR ] 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.80–0.98). [23]

In total, an estimated $12.6 billion per year is spent in OAB-related costs in the United States (see the image below). Some of these costs (eg, those related to physician visits, protective devices, management of UTIs, and skin infection and irritation) are obvious. Others are not. For example, decreased productivity and lost wages due to OAB is estimated to cost $841 million per year.

Total community and institutional costs of overactive bladder (OAB) (in millions of dollars). UTI—urinary tract infection (UTI). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Total community and institutional costs of overactive bladder (OAB) (in millions of dollars). UTI—urinary tract infection (UTI). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

These estimates do not reflect the intangible OAB-related costs, such as time spent by family members away from work to care for elderly patients with OAB, to accompany them to physician visits, to shop for protective devices, and to help with toileting and laundry. Therefore, the cost figures underestimate the economic impact of OAB. [24]

Management of OAB can decrease the economic impact of OAB. Two studies have demonstrated cost savings related to medical management of OAB. In both of these studies, savings were achieved by reducing the comorbidities of UTI and skin infection and irritation. [25, 24]

-

Communication between urothelium and suburothelium. ACh—acetylcholine; ATP—adenosine triphosphate; M2—muscarinic receptor subtype 2; M3—muscarinic receptor subtype 3; NO—nitric oxide; P2X1—purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel 1; P2X3—purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel 3; sGC—soluble guanyl cyclase; VR1—vanilloid receptor 1.

-

Overactive bladder (OAB) and quality of life (QoL). Short Form-36 (SF-36). Reprinted with permission from Blackwell.

-

Total community and institutional costs of overactive bladder (OAB) (in millions of dollars). UTI—urinary tract infection (UTI). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.