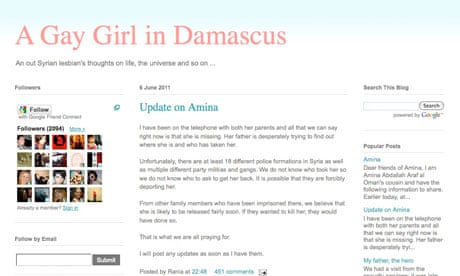

There was nothing, at first sight, to indicate the website was not exactly as it appeared. A young woman living in Damascus, with dual US and Syrian citizenship, blogging in passionate, moving and deeply personal terms about her life as a lesbian and political activist living through the events of the Arab spring.

"Almost every time I speak or write to other LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender] people outside the Middle East, they always seem to wonder what it's like to be a lesbian here in Damascus," Amina Abdallah Araf al Omari wrote on 19 February in the opening post of her blog, A Gay Girl in Damascus. "Well, I always find myself answering, it's not as easy as I'd like it to be but it's probably easier than you might think. And that, of course, opens up a whole endless stream of questions …"

For 106 days Araf, a 35-year-old with a glossy brown bob and a distinctive mole over her left eyebrow, described daily life at home in a large house in the old city of Damascus, where she lived with her father. He knew of her sexuality, she wrote, and was supportive.

As Syria's popular uprising gained momentum, however – and with it the government's violent response – the outspoken activist described an ever more precarious life; eventually, she wrote of being forced into hiding. Her blog was gaining a growing following, and she gave an interview by email to CNN and agreed to talk in person to the Guardian's correspondent in Damascus, though she did not show up to that meeting, as is not uncommon for activists in the city, saying she had seen secret police at the rendezvous cafe.

On Monday a post appeared on the blog signed by Araf's cousin Rania O Ismail, saying the activist had been snatched by security forces from a street, and prompting headlines around the world.

That's when the questions began. Andy Carvin, a senior strategist at the US broadcaster NPR, who has become a key hub of Twitter contacts throughout the Middle East, wrote that he had been contacted, separately, by Syrian sources who said they had doubts about some of the details in the blog. No one in the Syrian lesbian and gay community seemed to have heard of her, and some details – such as when she wrote that secret police who had come to arrest her left after her father stood up to them – did not ring true.

Separately, a young woman from London, Jelena Lecic, had seen the press coverage of Araf's kidnapping, and contacted media organisations to say the pictures published around the world were not of an Arab lesbian, but had been taken from her own social media sites. The Guardian's website removed the photograph, taken from a Facebook page calling for Araf's release, and replaced it with an image that had been emailed directly to the Damascus correspondent by the person claiming to be Araf.

That, too, was removed following a complaint from Lecic that it was also a picture of her. Individuals who had become friends on Facebook with "Amina Arraf" would then emerge to say that as many as 200 separate pictures had been posted on to that site, some of them tagged and commented upon as if they were of Araf – all of which were in fact of Lecic.

So at least some of the details on the blog were lies. Were any true? The US embassy in Damascus knew of no one called Amina Abdallah Araf al Omari among the 4,000 American citizens in Syria, nor of any young woman fitting her description who had been taken into custody. Searches of public records in Virginia, where the blogger said she was born, or Georgia, where she claimed to have gone to high school and later university, revealed no one by her name or the name she gave for her mother.

Despite the efforts of major news organisations, bloggers and enterprising individuals on the internet and Twitter, no one – journalist, activist, friend or Facebook contact – has been identified who has ever spoken to Araf face to face. Sandra Bagaria, a French Canadian had exchanged more than 500 emails with her, but on the one occasion she had tried to speak to her in person she got no answer. A reporter from NPR would later call the number and reach a pharmacy in Damascus. They had never heard of Araf.

Is A Gay Girl in Damascus a cynical hoax? Days after the mysterious post by Rania O Ismail, concrete evidence that it is all a fiction remains absent. Even the fake photographs and apparently false names are not, in themselves, proof that the story of a lesbian activist in a Syrian jail is a fiction. More than 10,000 people are thought to have been picked up by Syrian secret police since the uprising began, and if Araf is not being mistreated in custody, as repeated commentators have pointed out, there are plenty like her who are. It is common, similarly, for activists to use false names to obscure their identities.

But what remains, which means the mystery will not go away, is an absence. Why has Rania O Ismail, who according to a Facebook page and other social media sites is based in the US, not updated what she knows, given the internet storm over the blog?

In a post entitled "Painful doubts about Amina", the feminist blogger Liz Henry, who had featured writings by Araf in the past, wrote of her experience in 2003 with the blogger Plain Layne.

"Her life as a bisexual young woman was full of drama; she was goodhearted, generous, incredibly engaging, a fabulous writer, and would sometimes get herself into situations that would just make you stay awake at night worrying about her life … it was quite incredible.

"Well … to make a long story short Plain Layne turned out to be this middle-aged guy named Odin Soli who had also won blog awards years before as Acanit, a young lesbian Muslim girl with a Jewish girlfriend."

If Odin, who now describes himself as a writer of "online fiction", could do it, she suggested painfully, there was no reason Amina Araf could not be another fake.

If it is an internet joke, it could be hugely damaging, activists fear. Daniel Nassar, the pseudonym of a gay campaigner in Damascus, told the Guardian none of his gay friends had met or heard of Amina, but they feared what the backlash to a fake blog could lead to.

"I changed my Twitter name (which was my real name) and picture (which was my real picture) after the news of Amina [emerged]," he said. "I wasn't afraid of what happened to Amina, as I felt she was fake … I was afraid of the aftermath of her silly lie and how would it affect the way police treat LGBT people here."

But if the Gay Girl in Damascus is indeed a hoax, it is a fantastically elaborate one. Cached pages on social media and dating websites suggest "Amina Araf" has an internet identity dating back at least to 2007. Online friends on various sites say they have corresponded extensively – always by text – with someone they believe to be Araf. Several of the pictures of Lecic on the faked Facebook page were uploaded there last year or earlier, according to those who have seen them.

"Maybe she has all the reasons to be hiding, to just not speak out," Begaria told NPR. "Maybe she is really detained. Maybe there is someone really called Amina being in jail. "Of course I have doubts, of course, of 'is it true?', 'what is not true?'" Bagaria told NPR. "But again I am quite certain there is really someone writing. Now, the face that she has, I don't know. But there is someone."