Horror aficionados judge onscreen zombie special effects by the quality of the cranial gunshots that kill the ghouls. The cameras of AMC's show The Walking Dead linger on the aftereffects of gunshots to the heads of their undead in a way that can only be described as lavish. The show's just-completed first season has been serious, emotional, well-written and epic. But for those kind of people who are obsessed with this genre—like me—the grotesque, unflinching headshots became another mark of quality programming.

This is not as ghoulish as it may first appear. The amount of time and effort devoted to this gory special effect is directly proportional to the amount of time, money and gravitas given to the movie or, in this case, TV show. A serious effort like The Walking Dead should have special effects on par with the show's approach. And for those who want to go deeper into the zombie mythos, the way the undead can be killed speaks volumes about the rules that govern their unnatural existence. More than a werewolf or vampire, zombies beg for a rational explanation of how they function. In a body that is rotting on the bone, what part of the brain needs to be destroyed to put them down for good, and why?

To get a sense of how The Walking Dead team approaches its undead head trauma, I called Greg Nicotero, head of special effects for the show. "My first job was making squibs (explosive packets filled with fake blood) for Day of the Dead," he says. In 1985, when that film was made, a VFX artist trying to create a head shot could attach gunpowder-ignited sack onto the noggin of an actor or extra (protected by a plate, of course) and detonate a bag filled with red fluid and faux brain material. Another method involves yanking cords that spill blood bags hidden behind prosthetics. These days, that explosive approach can only be used on a stuntman and the wire plug method is time intensive.

Since television shows have tighter shooting schedules than films, Nicotero invented an easy-to-refill system for The Walking Dead's head shots. A tube of blood and brains is attached to the back of the zombie actor's neck, and the tube is connected to a bellows. A stomp on the bellows forces air through the tube, blowing out the blood and other material in a crimson spray. The crew can stretch the air line 10 feet, giving the stricken zombie some range. The entry wound and subsequent blood dribble is added later by digital effects artists. There are no prosthetic body parts to repair and no charges to rearm. Nicotero says the use of physical blood bags helps make every headshot different. "They all have their own personalities," he says.

To that end, The Walking Dead special effects team tailors their head hits to the action on the screen. "We have forensic textbooks that we use to match wounds with weapons," Nicotero says. "Part of our job is doing research into the ways that bullets go in and come out, how they fragment and how large the exit wounds are."

Less attention is paid to the morphology of the zombies themselves. In terms of what kills zombies, Nicotero says The Walking Dead is "such an homage to the original, George Romero" that there was never a serious consideration to change the cardinal rule that only a headshot can kill them. "I remember I had an early conversation with (director) Frank Darabont where we tried to define what happened, of what the source of the outbreak was," he says. They decided against such a move, not wanting to expose the fledgling series to rules that could limit the direction of the plot. Likewise, the way to kill a zombie is very familiar. "George made up the rules," Nicotero says. "Now people just know it's what you have to do during a zombie outbreak; destroy the brain or sever the head from the body...We stuck with that tried-and-true mythology."

Luckily, others have entered that conversation, seeking deeper answers. It's time to hit the medical books.

The Science of Head Hits: The Frontal Lobe

Dr. Steven Schlozman, has written extensively about the brain function of undead zombies (as opposed to voodoo victim zombies). He's co-director of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and, much more importantly, on the advisory board of the Zombie Research Society.

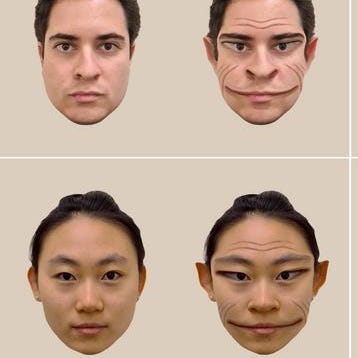

His self-appointed mission is to use zombie fiction to help teach people about the way the human brain works. One of the useful points he makes is that, contrary to the idea that the brain stem (medulla oblongata) must be destroyed in order to destroy a zombie, their behavior indicates that several parts of their brains are still functioning in a coordinated way. They hear noise, stagger toward it and attack the target on sight. These are sure signs that the zombie frontal lobe is active enough to process sensory input through the thalamus. Of course, the frontal lobe must be damaged because the zombie acts on base impulses, like pursuing and eating other people. Other brain damage accounts for the lack of motor coordination and general poor manners.

The good news here for zombie apocalypse survivors—and defenders of the logic of zombie shows—is that damage to other parts of the brain could put a zombie down for good. So any nitpicking over the effectiveness of arrows and blunt instruments to destroy the undead could be unfounded. That's not to say that these weapons are better than a firearm. Guns are the best brain destroyers out there, but there's more than meets the eye there, as well. Many parts of the brain can take damage while the body stays functional.

So the last stop of a zombie headshot enthusiast (with plenty of free time) must be forensics journals. It turns out there are three kinds of people who are keenly interested in the way gunshots can lead to "immediate incapacitation": police accused over pulling the trigger too many times, military snipers and zombie genre nuts. In most zombie-scenarios a wounded zombie still poses a massive danger and ammunition is likely in short supply, so knowing what part of the brain needs to be destroyed to prompt an immediate shut-down is useful. In this, the 1995 study "Penetrating gunshots to the head and lack of immediate incapacitation" by German researcher B.L. Karger is required reading. As is "Forensic neuropathology: a practical review of the fundamentals" by Hideo Itabashi.

Karger lays down the basics ("immediate incapacitation is possible following cranio-cerebral gunshot wounds or wounds that disrupt the upper cervical spinal cord only") and Itabashi backs the conclusions with specifics, and nauseating color photos. Itabashi says that immediate incapacitation is "very likely" in head shots by a rifle or shotgun at close range, or handguns with calibers larger than 9mm. Nothing too surprising there, but the locations of the wounds is of interest to zombie hunters. Itabashi says that hitting the brain stem or severing the spinal column between the second and third thoracic vertebrae (in the neck) will produce an instant kill, which follows the canon of typical zombie scripts. But he also includes a third location in the brain as a place where damage results in immediate incapacitation—and it's located frontal lobe. The primary motor cortex exists on both sides of the brain. It sends signals, via neurons, to the muscles of the body. Destroy this and you have a harmless zombie.

None of this zombie obsession surprises Nicotero, who's been in the vanguard of the undead scene since the '80s. "Zombies are now mainstream," he says. "I talked to the zombie extras from The Walking Dead set; eight are going to ComiCon to sign autographs."

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.