Three weeks ago, the University of Mumbai, one of India's oldest and most prestigious educational institutions, suddenly dropped Rohinton Mistry's poignant debut novel, Such a Long Journey, from its English literature syllabus.

The Commonwealth prize-winning fiction, which was on the 1991 Booker shortlist, was proscribed mid-term after the student wing of the nativist Shiv Sena party burned copies to protest against the "obscene and vulgar language" and the allegedly derogatory remarks about the party, its leader Bal Thackeray and the locals of the state whose cause it claims to champion.

Liberal groups campaigning for the text to be restored were further disheartened when the state's Congress chief minister announced that he too had found some paragraphs to be "highly objectionable". Disheartened perhaps, but scarcely surprised. The politics of competitive parochialism has always been far more lucrative to politicians than what they dismiss as a salon conversational subject: freedom of speech.

That the 20-year-old text has been taught in Mumbai's colleges for four years without event made not a whit of difference. The chief minister admits that apart from the offending paragraphs, he has not read the book. Neither has Bal Thackeray's grandson, Aditya Thackeray, the boy-politician leading the protest.

Kangaroo censorship and book-burning is a bullying tactic frequently used by India's political parties, strangely thick-skinned about all else but cultural criticism. In 1995, Salman Rushdie's The Moor's Last Sigh had the distinction of being burned both by the Sena and the Congress for its caricature of Bal Thackeray and for daring to have a stuffed dog on wheels named Jawaharlal Nehru.

In 2004, a library of priceless oriental manuscripts in Pune was ransacked by a political mob objecting to a history book on the Maratha warrior king, Shivaji. The fact that book-burners are rarely brought to justice only encourages such displays of lumpen censorship.

But what has rattled civil society this time is the manner in which the vice-chancellor, who is expected to be the guardian of intellectual freedom, buckled so swiftly, dropping the text without even the fig leaf of "due process". The issue has focused attention on how political appointees are being elevated to positions of academic authority, thereby putting in peril the very future of education. Few will contest that the University of Mumbai is on such a wrong journey.

If there is a redeeming feature to this sorry episode, it is the quality of protest it has provoked. Redeeming because the Shiv Sena, which has a reputation for violence, is rarely countered. An online petition is being circulated, book readings held and bookstores deluged with orders for the novel. In a written statement, Dr Frazer Mascarenhas, the Jesuit principal of St Xavier's College which Mistry attended and where Aditya Thackeray is currently enrolled, asked the all-important question: "Is it not unreasonable, that literature is banned merely because it dares to critique us?"

Mistry sent in his response from his home in Canada. In an eloquent and erudite statement that was carried on the front pages of India's leading newspapers, Mistry recalled Rabindranath Tagore's rousing poem about freedom. In stinging but measured prose, he admonished the vice-chancellor for being "silent on the matter of moral responsibility". He did not name the vice-chancellor, addressing instead the high office of the chair and the "abuse" of its powers. For the young Thackeray, he had some haunting Conradian wisdom: step back from the abyss, or go over the edge.

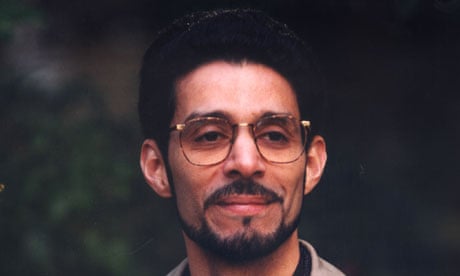

One of Mumbai's finest chroniclers, Mistry excavates with tragicomic detail the warts-and-all skin and soul of the city of his birth and youth. A few years ago, Mistry said on Oprah Winfrey's Book Club show that the reason he continued to write about Bombay was "because of the people, their capacity for laughter, their capacity to endure".

The 1971 canvas of Such a Long Journey evokes a Bombay of mutton samosas, prostitutes and convent schools, spies who use lines from Othello to pass on messages and public walls which need god-photos to keep them clean. Mistry bends his ear to the city's slang and salty Parsi humour to capture the lives of people encircled by a corrupting political darkness. If the Shiv Sena is written about in unflattering, ribald terms, so is Indira Gandhi and her Congress government and so are the American and Pakistani governments of the time.

Mistry's bank-clerk hero, Gustad Noble, is a Tolstoyan figure repeatedly short-changed by life. His city is closing in on him. His country is going to war. And yet he says his prayers and limps on, driven by a stubborn moral compass and the will to give his children a future. Movingly, despite his sea of troubles, he is riven by the plight of the Bengali refugees fleeing the ravages of war. The novel ends with Noble unpeeling the war-regulation black paper from his windowpanes.

The Shiv Sena-triggered, Congress-condoned, vice-chancellor-executed university ban on the book is nothing more than a crude attempt to re-paper those windows.