This case study describes how four school systems conducted pilot programs and analyzed data during their participation in The Learning Accelerator’s (TLA’s) Strategy Lab program. Teams leveraged TLA’s Real-Time Redesign process to identify and implement solutions for challenges to equity in their virtual and hybrid learning schools.

Key Points and Takeaways

For students to thrive in a virtual/hybrid learning environment, it is essential for schools and teachers to implement practices that foster student engagement.

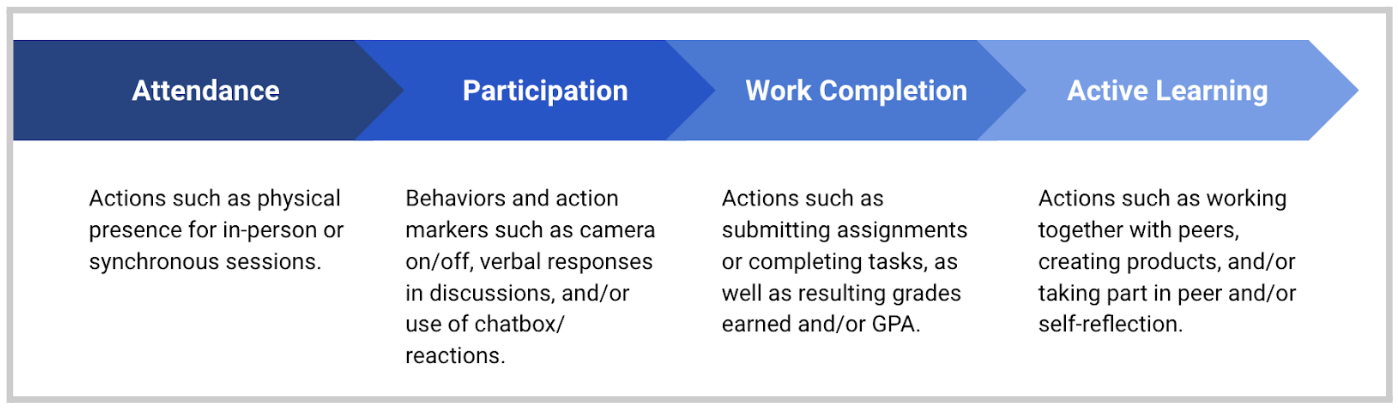

Definitions of “engagement” vary from more superficial measures (attendance, participation, and work completion) to demonstrations or more active learning – such as how students are interacting, making meaning, and signifying understanding with peers and adults in interactive and participatory activities.

While we ultimately want to aim for conceptualizing engagement deeply, challenges to engagement can exist at more foundational levels. Approaches need to effectively diagnose and address the right level of the engagement continuum.

Teachers must be empowered to create and implement effective instructional strategies that encourage students to actively participate in their learning – such as creating content, collaborating with peers, or producing an end product.

Decision-makers can tackle this challenge in their own setting by first digging in deep with stakeholders to gather data on the nature of their challenge, exploring promising existing solutions and approaches, and testing in their own context. This case study offers examples from four school systems that undertook this work.

What the Research Says About Student Engagement

Since the 1890s, educational philosophers such as John Dewey (1916) [1; see full reference list below] have touted the importance of viewing students as active learners. Yet, since the invention of the Carnegie Unit in 1906, learning has often been equated with seat time (and measured through means like attendance and time on task) rather than quality and mastery of content. The term engagement first emerged in relation to education in a study conducted by Natriello in 1984 [2]. He equated engagement with participation, measuring it by the extent to which students did or did not take part in school-based activities, and incorporated the understanding that both attendance and student effort influenced student academic achievement [3].

The importance of engagement continues to resonate with stakeholders [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] (i.e., policy-makers, researchers, educators, families, and students), and strong evidence indicates that it is a key factor for learning [10, 2]. Given this, how do we know students are actually “engaged” in their learning, and how can we increase engagement?

The term “engagement” typically evokes an active image (e.g., talking, writing, drawing), but it also occurs on an internal level that is not easily observable (e.g., thinking, processing, reflecting). Researchers have commonly defined engagement along three different dimensions [11]:

Cognitive (thinking) engagement: An internal process through which students make sense of or process what they are learning [12]

Emotional (feeling) engagement: An internal process through which students interact or react emotionally to what they are learning

Behavioral (acting) engagement: An external process through which students physically demonstrate or interact with what they are learning

Understanding and tackling the challenge of student engagement can be especially difficult for educators, parents, and students in virtual and hybrid classrooms. Given more limited proximity and visibility, research suggests that effective engagement (via a foundation for self-directed learning and key components of effective instruction, including technology, pedagogy, and relationships) becomes even more important in that learning experiences build on the effective features of in-person instruction but also actively address, mitigate, and leverage the distinct advantages and challenges presented by technology and out-of-school learning. An approach that integrates all of these factors allows for deep engagement and the fulfillment of students' unique learning needs.

The Challenge of Addressing Student Engagement

It’s clear from the research that, in order for students to succeed in a virtual/hybrid learning environment, it is essential for schools and teachers to implement practices that foster student engagement.

Because effective virtual and hybrid learning is highly dependent on opportunities that foster student engagement, teachers need to understand the importance of – and pedagogy behind – student-centered learning. Teachers and leaders must:

Have sufficient pedagogical knowledge to design instruction that is relevant and motivating for students, and offer opportunities for student voice and choice. For active learning to occur, teachers must be empowered to create and implement effective instructional strategies that encourage students to deliberately engage in their learning.

Establish clear routines and guidelines for students so they know how to communicate with peers and teachers.

Establish a warm classroom environment so that students are comfortable collaborating with peers as they take risks in their learning.

Have access to the time and resources necessary to support active learning and use of engagement strategies.

Identify means for measuring and monitoring student engagement at a deeper level in context, rather than relying on more superficial means like attendance and participation in synchronous sessions (e.g., “camera on,” verbal response, use of a chatbox or reactions) or work completion (e.g., assignment submission, grades).

The 20 school system teams that participated in TLA’s Strategy Lab: Virtual & Hybrid program wanted to improve their instructional programs. The term engagement and its derivatives appeared 299 times throughout these teams’ coaching notes (with some teams using that term more frequently than others) – an indication that it was an important consideration for educators.

Even though each team identified a problem specific to their context, all of the challenges identified by these districts were in some way related to engagement – even if the teams did not specifically mention the term. For example, some districts identified attendance concerns in synchronous sessions, whereas others wanted to explore why some students struggled with completing tasks in their asynchronous classes. TLA considers engagement along a continuum from foundational tenets (i.e., attendance) to more meaningful forms (i.e., active learning).

Continuum of engagement from foundational tenets to more meaningful learning.

What We Observed in Strategy Lab Systems and Pilots

The continuum shown above appeared in the way systems operationalized their own definitions. Each system chose to focus on a tenet of engagement they identified through team discussions, as well as self- and team assessments, and that was aligned to their reason for joining Strategy Lab in the first place.

The needs assessments conducted by these four system teams revealed similar root causes to their problems of practice. However, they addressed different aspects of the engagement continuum from foundational tenets (i.e., attendance) to more meaningful engagement (i.e., active learning):

NYC School Without Walls sought to increase attendance for fieldwork opportunities by improving communication efforts and making stronger connections in class.

KJ Virtual Academy endeavored to increase participation in synchronous classes by modeling behaviors and prompting students during small-group literacy instruction.

KIPP DC’s Virtual Learning Program aimed to increase work completion by implementing targeted, one-to-one mentoring check-ins so teachers could encourage and assist students in submitting assignments.

Cabarrus Virtual Academy aspired to increase active learning by implementing a school-wide project-based learning (PBL) event that motivated students to collaborate in solving a real-world engineering problem.

The summaries below provide an overview of how these public school systems identified and addressed various degrees of student engagement, with links to individual case studies focused on each system that offer additional information and context.

NYC School Without Walls

NYC School Without Walls (SWOW) is a hybrid program with an enrollment of 60 students in grade nine, located in an urban district in New York.

Engagement as Attendance: Team members noticed that although student attendance rates were typically in the 80% range, attendance was noticeably lower on Fridays, which were typically reserved as fieldwork days.

Pilot: Address student engagement (attendance) by clearly communicating about fieldwork opportunities, holding student information sessions, and incorporating lessons with shared targets to increase attendance.

KJ Virtual Academy

KJ Virtual Academy is a hybrid school with an enrollment of around 70 PK-6 students in an urban district in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Engagement as Participation: Team members shared that students with lower attendance and participation (e.g., “camera on,” verbal responses) in synchronous classes also displayed lower literacy growth.

Pilot: Increase student engagement (participation) by teacher modeling of expected online behavior and holding students accountable during small-group synchronous sessions.

KIPP DC

KIPP DC is a virtual program in a charter school with an enrollment of 200 PK3-8 students, located in an urban charter school system in Washington, D.C.

Engagement as Academic Progress: Team members shared, “Students are coming. They’re generally happy. Now, are they learning?” In examining academic progress, they found that 40% of students who had a ‘D’ or ‘F’ also had an attendance rate below 80%, with 50% of students not turning on their cameras during class.

Pilot: Address student engagement (work completion) by implementing targeted advisory check-ins for students to encourage and help them complete assignments to raise their grades.

Cabarrus Virtual Academy

Cabarrus Virtual Academy is a hybrid school with an enrollment of 300 K-12 students, located in a suburban district in Concord, North Carolina.

Engagement as Active Learning: Team members noticed that their middle-school students did not have many opportunities to actively engage or collaborate with peers in their learning. They wondered to what degree their students were empowered in their learning.

Pilot: Increase student engagement (active learning) by implementing a cross-curricular, collaborative project-based learning (PBL) unit for all middle schoolers.

Each system chose a solution that was specific to their teachers, their learning context, and their students’ needs.

Because technology serves as the medium for communication, collaboration, and learning in virtual and hybrid classrooms, it is critical that teachers know how to encourage engagement across the spectrum – from setting routines and expectations for students to designing effective instruction that encourages active learning.

When dealing with challenges inherent in virtual/hybrid learning spaces, TLA recommends that systems reflect upon and leverage quality drivers (foundation for self-directed learning, technology, pedagogy, and relationships) to inform their policies and practices – especially as they relate to student engagement:

By increasing teacher capacity around how to design and implement engaging and meaningful learning experiences in the virtual/hybrid classroom, students will feel more engaged and motivated to learn.

By increasing teacher capacity on designing and implementing flexible and personalized learning experiences, students will be able to better engage with the material and their peers.

By increasing student capacity for self-directed learning, they will gain self-efficacy, be able to successfully access the content, and engage with their peers and teachers.

By improving communication between school and home, students and families will better understand the expectations for successful virtual/hybrid learning.

Taking It Forward

From the organization’s Strategy Lab work, TLA knows the problem of student engagement can be mitigated through the implementation of quality drivers for effective instruction: technology, pedagogy, and relationships. As TLA learned with the four schools highlighted in this case study:

Teachers need to know how to design effective instruction for synchronous and asynchronous learning;

Students need clear routines, expectations, and flexible/personalized opportunities for virtual/hybrid learning; and

Schools need to clearly communicate the expectations for active learning in a virtual/hybrid setting to all stakeholders – teachers, students, and families.

TLA acknowledges that change is hard – but sustaining data-driven, personalized approaches to teaching and learning requires coherent, system-wide shifts in both strategy and practice. As the four schools featured in this case study demonstrated, there is no single, correct pathway to address a common problem of practice – but there are measures system leaders and educators can take toward crafting solutions personalized for their own unique contexts.

As concrete action steps, TLA encourages leaders to begin addressing the challenge of student engagement by:

1. Building an inclusive team: Bring together a diversity of perspectives, ideas, and experiences.

2. Gathering data to understand the challenge: As a team, examine the quality of your virtual/hybrid learning environment.

3. Identifying and implementing the conditions necessary to support planning, adoption, and scaling of new initiatives: School systems must have a concrete vision for learning that describes how students will experience an engaging, effective, and equitable learning environment, and should communicate this vision clearly to all stakeholders. In addition, school systems need to foster a culture of change, cultivate relationships, and provide a sustainable professional learning program for educators.

4. Identifying and implementing promising practices: Teachers need to intentionally select strategies that foster and encourage student engagement in the virtual/hybrid learning environment, including real-time, flexible, and individualized options.

5. Measuring progress to inform improvement efforts: Designing measurable solutions lies at the heart of the Strategy Lab process. In addition to following Real-Time Redesign (RTR) – a framework for quickly making improvements that are scalable, iterative, and relevant to local needs – begin by exploring the strategies below.