Language row looms over Belgian election

- Published

The last government fell because of a language-based dispute

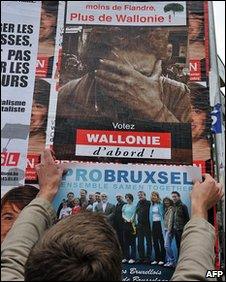

You can tell an election is due in Brussels because advertising hoardings are now plastered with posters, urging voters to support the multitude of parties on offer.

But when voters go to the polls on 13 June the backdrop will be the ongoing political crisis that has dogged the country since 2007 - if not longer.

Belgium is a country divided.

The southern region is home to mostly French speakers, who make up about 40% of the population. The other 60% are Dutch speakers who live in the Flemish north.

To add confusion, the capital Brussels is officially a bilingual (but largely francophone) enclave in Flemish territory.

The linguistic gulf runs deep. There are no national political parties - they too follow the language split, so there are both francophone and Flemish Liberal, Socialist, Christian Democrat and Green parties.

Likewise, there are no national broadcasters, no national newspapers or magazines.

Autonomy push

The Belgian state is already highly decentralised. Education, health, and transport are all the responsibility of powerful regional parliaments.

To make the system work, politicians from both communities have to co-operate. But in recent years that co-operation has broken down.

Some politicians from the wealthier Flemish region are pushing for even more autonomy, for example by taking control of the social security system.

French speakers from the more impoverished south fear that would mean the country breaking up.

These elections were called when - for the third time in as many years - the government collapsed.

The trigger was a complex argument over voting rights for French speakers living in Flemish towns on the outskirts of Brussels.

They have been allowed to vote for French language parties in the Brussels region, even though they live in a Flemish area.

The Constitutional Court ruled that was illegal. But all attempts to find a compromise have failed.

One man who tried was the former Prime Minister Jean-Luc Dehaene. Now a member of the European parliament, he is fairly relaxed about the political crisis gripping his country.

"It's not the first time. Let's say every 10, 15 years we have an evaluation and a renegotiation of the institutional consensus. Mostly that goes with some political friction, but mostly we come out!"

Mr Dehaene is putting his trust in "the Belgian compromise" - the willingness of politicians from both communities eventually to give a bit and work together.

But in an industrial estate just to the south of Brussels people are not sure the Belgian compromise is still functioning.

At the Milcamps factory they produce waffles, that quintessentially Belgian product.

International dimension

As we walk through the factory the air is filled with the sweet, mouth-watering scent of them, freshly baked.

Against the low din of clanking waffle irons, export manager Genevieve Roberti Lintermans says the political turmoil is not doing her country many favours.

"European countries where we sell a lot of product could be a little bit worried about the situation in Belgium - as we are," she says.

At the Milcamps factory they are not sure the compromise is working

"In Belgium we are very sad about what is happening - I mean the population is very sad."

And that is an interesting distinction. It is hard to find many Belgians who are that hung up about the voting rights of French speakers in dormitory towns around the capital.

Many feel it is an obsession of the political classes and would just like them to get on with running the country.

And there is an added international dimension.

The elections come just as Belgium is meant to be playing a leading role in the European Union.

Next month it takes on the EU presidency for the rest of the year, running meetings and with the chance to exercise a strong influence on the agenda.

"The elections take place right before the start of the presidency in July, which means they [Belgium's political leaders] will be in the middle of coalition talks as it starts," says Mike Beke, a researcher at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

He thinks that with the experience of running 11 previous presidencies, Belgium will cope, despite domestic distractions.

"On the other hand, the expertise and experience of the Belgian administrations [of running an EU presidency] won't affect their work [forming a coalition] too much," he adds.

So while the business of the Belgian state grinds on, complex negotiations will follow the elections on 13 June as politicians try to form another coalition government.

But at the moment it is hard to see the country's politicians overcoming the differences that have dogged them for years.