The Daniel Defoe event had just been cancelled, and as a consequence of this the queue for the tea tent was stretching half way round the meadow. Towards the back, shivering slightly this damp October morning, were two women who looked to be somewhere in the early November of their lives.

"Excuse me, but are you going to the next talk?" one of them asked the other, waving a festival brochure at a late lost wasp.

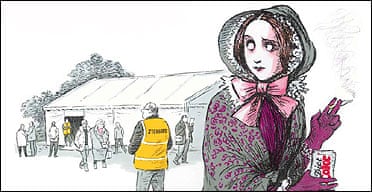

"Who, me?" replied the woman. "Yes. Yes, I am. It's Charlotte Brontë reading from Villette, I believe."

"Hmm, I hope they keep the actual reading element to a minimum," said the first, wrinkling her nose. "Don't you? I can read Villette any time."

"Good to hear it in her own voice, though," suggested the other.

"Oh I don't know," said the first. "I think that can be overdone. Some curiosity value, of course, but half the time an actor would read it better. No, I want to know what she's like. That difficult father. Terribly short-sighted. Extremely short full stop. The life must shed light on the work, don't you think. What's the matter, have I got a smudge on my face or something?"

"It's not ... ?" said the other, gazing at her wide-eyed. "It's not Viv Armstrong is it?"

"Yes," said Viv Armstrong, for that was indeed her name. "But I'm afraid I don't ..."

"Phyllis!" beamed the other. "Phyllis Goodwin. The ATS, remember? Bryanston Square? Staining our legs brown with cold tea and drawing on the seams with an eyebrow pencil?"

"Fuzzy!" exclaimed Viv at last. "Fuzzy Goodwin!"

"Nobody's called me that for over fifty years," said Phyllis. "It was when you wrinkled your nose in that particular way, that's when I knew it was you."

The rest of their time in the queue flew by. Before they knew it they were carrying tea and carrot cake over to a table beneath the rustling amber branches of an ancient beech tree.

"I'm seventy-eight and I'm still walking up volcanoes," Viv continued, as they settled themselves. "I don't get to the top any more but I still go up them. I'm off to Guatemala next week."

Eager, impulsive, slapdash, Phyllis remembered. Rule-breaking. Artless. Full of energy. In some ways, of course, she must have changed, but just now, she appeared exactly, comically, as she always had been, in her essence if not in her flesh. Although even here, physically, her smile was the same, the set of her shoulders, the sharpness of nose and eyes.

"The first time I saw you, we were in the canteen," said Phyllis. "You were reading The Waves and I thought, ah, a kindred spirit. I was carrying a steamed treacle pudding and I sat down beside you."

That's right, thought Viv, Fuzzy had had a sweet tooth-look at the size she was now. She'd had long yellow hair, too, just like Veronica Lake, but now it was short and white.

"I still do dip into The Waves every so often," she said aloud. "It's as good as having a house by the sea, don't you think? Especially as you get older. Oh, I wonder if she's on later, Virginia, I'd love to go to one of her readings."

Viv knew many writers intimately thanks to modern biographers, but she was only really on first name terms with members of the Bloomsbury group.

"Unfortunately not," said Phyllis. "That's a cast iron rule of this festival, a writer can only appear if they're out of copyright, and Virginia isn't out of it for another five years".

"But she must be, surely," said Viv. "Isn't copyright fifty years?"

"Well it was, until recently," said Phyllis. "And Virginia was out of it by the early nineties, I happen to know because I was at one of her readings here. Oh, she was wonderful. What a talker! She kept the whole marquee in stitches - spellbound - rocking with laughter. But then they changed the copyright law, something to do with the EU, and now it's life plus seventy years, and she went back in again. So she won't be allowed to return until 2011 at the earliest. Very galling as we might not still be here by then."

"Oh I don't know," said Viv. "Aren't you being rather gloomy? Seventy-eight isn't that old."

"It is quite old, though," said Phyllis doubtfully.

"Well I suppose so. But it's not old old," said Viv. "It's not ninety. Come on, now, Fuzzy, we've got some catching up to do."

In the next few minutes they attempted to condense the last half-century into digestible morsels for each other. Viv had put in a year at teacher training college then found teaching posts through Gabbitas- Thring, while Phyllis had taken a secretarial course at Pitman's College in Bloomsbury followed by a cost accounting job at the Kodak factory where she lived, totting up columns of figures in a large ledger at a slanting desk. At some point between the Olympics being held at White City and the year of the Festival of Britain, they had met their respective husbands.

"All this is such outside stuff, though," said Phyllis obscurely. She was supposed to be writing her memoirs, spurred on by a local Life-writing course, but had been dismayed at her attempts so far, so matter-of-fact and chirpy and boring.

They ploughed on. Viv had settled just inside the M25, before it was there, of course, while Phyllis lived just outside it. They had had three children each, and now had seven grandchildren between them.

"Two girls and a boy," said Viv. "One's in computers, one's a physiotherapist and one has yet to find his feet. He's forty-eight."

"Oh," said Phyllis. "Well I had the other combination, two boys and a girl. Ned's an animal feed operator but his real love is Heavy Metal, much good it's done him. Peter's an accountant - no, I keep forgetting, they don't call them accountants any more. They're financial consultants now."

"Like refuse collectors. 'My old man's a dustman.' Remember that?" said Viv. "Then there was 'My old man said follow the van, and don't dilly-dally on the way.' My mother used to sing that. I divorced my old man, by the way, sometime back in the seventies."

"I'm sorry," said Phyllis.

"Don't be silly," said Viv. "I've realised I'm a natural chopper and changer. Or rather, I start off enthusiastic and then spot the feet of clay. It's a regular pattern. I did eventually find the love of my life, when I was in my sixties, but he died. What about your daughter, though? Didn't you mention a daughter?"

"Yes," said Phyllis, blinking. "Sarah. She went into the book business. In fact, she's the one who dreamed up the idea behind this festival, and now she runs it. Artistic Director of the Festival of Immortals, that's her title."

"Good Lord," said Viv. "The opportunities there are for girls these days!"

" It's a full-time year-round job as you can imagine," said Phyllis, gaining confidence. "She spent months this year trying to persuade Shakespeare to run a workshop but the most she could get him to do was half-promise to give a masterclass in the sonnet. He's supposed to be arriving by helicopter at four this afternoon but it's always touch and go with him, she says, it's impossible to pin him down."

"Good Lord", said Viv again, and listened enthralled as Phyllis told her anecdotes from previous years, the time Rabbie Burns had kept an adoring female audience waiting 40 minutes and had eventually been tracked down to the stationery cupboard deep in congress or whatever he called it with Sarah's young assistant Sophie. Then there was the awful day Sarah had introduced a reading as being from The Floss on the Mill and George Eliot had looked so reproachful, even more so than usual, but Sarah did tend to reverse her words when flustered, it wasn't intentional. Every year Alexander Pope roared up in a fantastic high-powered low-slung sportscar, always a new one, always the latest model. Everybody looked forward to that. Jane Austen could be very sarcastic in interviews if you asked her a question she didn't like, she'd said something very rude to Sarah last year, very cutting, when Sarah had questioned her on what effect she thought being fostered by a wet-nurse had had on her. Because of course that was what people were interested in now, that sort of detail, there was no getting away from it.

Last year had been really fascinating, if a bit morbid, they'd taken illness as their theme - Fanny Burney on the mastectomy she'd undergone without anaesthetic, Emily Brontë giving a riveting description of the time she was bitten by a rabid dog and how she'd gone straight back home and heated up a fire iron and used it herself to cauterise her arm. Emily had been very good in the big round table discussion, too, the one called "TB and Me," very frank. People had got the wrong idea about her, Sarah said, she wasn't unfriendly, just rather shy; she was lovely when you got to know her.

"They've done well, our children, when you think of it," commented Viv. "But then, there was no reason for them not to. First-generation university."

Phyllis had tried to describe in her memoir how angry and sad she had been at having to leave school at fourteen; how she'd just missed the 1944 Education Act with its free secondary schooling for everyone. Books had been beyond her parents' budget, but with the advent of paperbacks as she reached her teens she had become a reader. Why couldn't she find a way to make this sound interesting?

"Penny for your thoughts, Fuzzy," said Viv.

"Viv," said Phyllis, "Would you mind not calling me that? I never did like that name and it's one of the things I'm pleased to have left in the past."

"Oh!" said Viv. "Right you are."

"Because names do label you," said Phyllis. "I mean, Phyllis certainly dates me."

"I was called Violet until I left home," confessed Viv. "Then I changed to Viv and started a new life."

"I always assumed Viv was short for Vivien," said Phyllis. " Like Vivien Leigh. I saw Gone with the Wind five times. Such a shame about her and Laurence Olivier."

"Laurence Olivier as Heathcliff!" exclaimed Viv. "Mr Darcy. Henry V. Henry V! That was my first proper Shakespeare, that film."

"Mine too," confessed Phyllis. "Then later I was reading 'The Whitsun Weddings', - I'd been married myself for a while - and I came to the last verse and there it was, that shower of arrows fired by the English bowmen, just like in the film. The arrows were the new lives of the young married couples on the train and it made me cry, it made me really depressed, that poem."

"Not what you'd call a family man, Philip Larkin," said Viv.

"Not really," said Phyllis. "You know, thinking about it, the only time I stopped reading altogether was when they were babies. Three under five. I couldn't do that again."

"I did keep reading," said Viv. "But there were quite a few accidents. And I was always a Smash potato sort of housewife, if I'm honest."

"I wish I had been," said Phyllis enviously.

She cast her mind back to all that; the hours standing over the twin tub, the one hundred ways with mince, nagging the children to clean out the guinea pig cage, collecting her repeat prescription for Valium. That time too she had tried to record in her memoir, but it had been even more impossible to describe than the days of her girlhood.

"It's not in the books we've read, is it, how things have been for us," said Viv. "There's only Mrs Ramsay, really, and she's hardly typical."

"I've been bound by domestic ties," said Phyllis. "But I'm still a feminist."

"Are you?" said Viv, impressed.

"Well I do think women should have the vote so yes, I suppose I am. Because a lot of people don't really, underneath, think women should have the vote, you know."

"I had noticed," said Viv.

"It's taken me so long to notice how the world works that I think I should be allowed extra time," said Phyllis.

At this point she decided to confide in Viv about her struggles in Life writing. For instance, all she could remember about her grandmother was that she was famous for having once thrown a snowball into a fried fish shop; but was that the sort of thing that was worth remembering? Another problem was, just as you didn't talk about yourself in the same way you talked about others, so you couldn't write about yourself from the outside either. Not really. Which reminded her, there had been such a fascinating event here last year, Sarah had been interviewing Thomas Hardy and it had come out that he'd written his own biography, in the third person, and got his wife Florence to pretend that she'd written it! He'd made her promise to bring it out as her own work after he'd died. The audience had been quite indignant, but, as he told Sarah, he didn't want to be summed up by anybody else, he didn't want to be cut and dried and skewered on a spit. How would you like it, he'd asked Sarah and she'd had to agree she wouldn't. This year she, Sarah, had taken care to give him a less contentious subject altogether - he was appearing tomor-row with Coleridge and Katherine Mansfield at an event called The Notebook Habit.

"Yes," said Viv, " I've got a ticket for that."

This whole business of misrepre-sentation was one of Sarah's main bugbears at the Festival, Phyllis continued. She found it very difficult knowing how to handle the hecklers. Ottoline Morrell, for example, turned up at any event where DH Lawrence was appearing, carrying on about Women in Love, how she wasn't Hermione Roddice, how she'd never have thrown a paperweight at anyone, how dare he and all the rest of it. Sarah had had to organise discreet security guards because of incidents like that. The thing was, people minded about posterity. They minded about how they would be remembered.

"Not me," said Viv.

"Really?" said Phyllis.

"I'm more than what's happened to me or where I've been," said Viv. "I know that and I don't care what other people think. I can't be read like a book. And I'm not dead yet, so I can't be summed up or sum myself up. Things might change."

"Goodness," said Phyllis, amazed.

"Call no man happy until he is dead," shrugged Viv, glancing at her watch. "And now it's time for Charlotte Brontë. I had planned to question her about those missing letters to Constantin Heger, but I don't want Sarah's security guards after me."

The two women started to get up, brushing cake crumbs from their skirts and assembling bags and brochures.

"Look, there's Sarah now," said Phyllis, pointing towards the marquee.

Linking arms, they began to make their way across the meadow to where the next queue was forming.

"And look, that must be Charlotte Brontë with her, in the bonnet," Viv indicated. "See, I was right! She is short."